To glaze or not to glaze

Q:

I have a question related to ceramic crowns. Over the 10 years I have practiced, I have placed many porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns, but recently I am placing more full-zirconia and IPS e.max crowns. On routine recall appointments, I see many of the older crowns that were esthetically pleasing when initially placed are now looking too light. What is happening? Can I avoid this problem with my crowns? Some of mine are now esthetically objectionable.

MORE FROM DR. GORDON CHRISTENSEN |Making decisions on clinical topics

A:

The answer to your first question is relatively easy. However, avoiding the problem is not easy. I will attempt to answer both of your questions.

Providing accurate shade communication to your laboratory

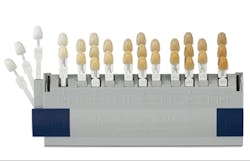

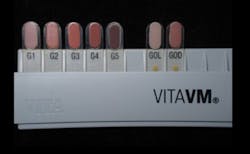

Transferring an accurate estimation of color to the laboratory is the first important point. As you know, matching the color of human anterior teeth is often a formidable task. Most dentists still use the original Vita Classical Shade Guide (Vita North America) when transferring the color of teeth to a laboratory (figure 1). Although this guide is still useful, other more recently developed guides are more adequate. The Vita Toothguide 3D-Master Shade System (Vita North America) with 26 shades and three bleach shades is much more adequate in transferring information to a laboratory (figure 2).

Figure 1: The Vita Classical Shade Guide is used widely, but it has some limitations.

Figure 2: The Vita 3D-Master Shade Guide has made color matching much easier than in the past.

If you send your lab a photograph of the teeth to be restored with at least two shade tabs adjacent to the teeth, the technician has a much better estimate of the colors to be matched to work with. Figure 3 shows that being done with the Vita 3D-Master Shade Guide for the two crowns to be placed on the maxillary central incisors. By using this technique, our technicians are able to match the color of the teeth very closely (figure 4).

Figure 3: Photographing the teeth to be restored with two shade tabs close to the color of the teeth is a major help for technicians.

Figure 4: The patient shown in Figure 3 was served well with two ceramic crowns on the central incisors.

For some cases where you are attempting to add gingival-colored ceramic to the apical portion of the restorations, a gingival shade guide is also very useful (figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Occasionally, gingival-colored ceramic is required on the apical portion of restorations. You need gingival shade guides.

Figure 6: A sample gingival shade guide.

Figure 7: Patient with color degeneration on crowns on the maxillary right side.

Figure 8: The patient in Figure 7 with ceramic crowns now serving at about eight years without color change.

When you provide photographs of the teeth and shade guide tabs that represent the color adequately, the laboratory technician is usually capable of reproducing the color of the teeth closely. This reduces the necessity to stain and glaze the ceramic subsequently. Our research has shown that stains usually come off quickly, leaving the crowns lighter than the natural surrounding teeth.

MORE FROM DR. GORDON CHRISTENSEN | Why do I need cone beam?

Why do technicians usually stain and glaze indirect restorations?

The superficial stains and glazes placed on the external of ceramic restorations have long been the method of closely simulating tooth color. These stains and glazes must melt at a lower temperature than the body of the ceramic or it will melt. With some ceramics, and assuming a knowledgeable technician is fabricating the restorations, the fusing temperature of the body of the ceramic can be approached very closely without melting it, and the stains can fuse into the body of the restoration. This is the ideal situation, and it provides a relatively stable surface smoothness and color for the restoration. However, that condition is not realized all the time, and the superficial stains and glaze that fuse at a lower temperature than the body ceramic are only slightly fused to the body of the restoration, and they soon dissolve or wear off. The result is a lighter-colored restoration, and often a visibly rough ceramic surface.

The two challenges described above are inadequate tooth color transfer to the lab by the dentist, necessitating subsequent color change by staining, and inadequate placement of stains and glazes by lab technicians. These are probably the main reasons why some restorations appear lighter after service in the mouth.

Figures 7 and 8 show an oral rehabilitation on a dentist before and after treatment. Figure 7 shows the mismatched colors of the restorations that had been placed years earlier. The dentist patient informed me that the restorations matched when placed, but it is obvious that the crowns on the maxillary right side no longer match. In contrast, the veneers on the maxillary anterior teeth have not changed color significantly. I can only speculate that the veneers' stains were probably applied at a temperature nearly at the temperature of the body of the veneer ceramic, and they have retained their color relatively well. Another possibility of why they have retained their color is that the original body color was adequate, and significant stain was not applied at the seating appointment. Both reasons have been discussed above.

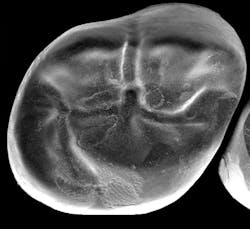

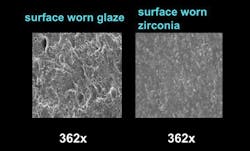

Electron microscopic research accomplished by the TRAC Division of Clinicians Report Foundation has shown that stains on the new zirconia and lithium disilicate crowns also wear off very rapidly. Figure 9 shows an electron microscopic image of a zirconia crown that was in the mouth for only a short time with areas of glaze worn off. Figure 10 shows how worn glazed surfaces are rough when subjected to occlusal forces and wear, and how relatively smooth the surface zirconia is at the same magnification.

Figure 9: Glaze wear on a zirconia crown.

Figure 10: Electron microscopic images of worn glaze and zirconia in occlusion not glazed at the same magnification.

Some are suggesting staining and glazing only the facial surfaces of restorations. However, while facial stains do not wear as rapidly as occlusal surface glaze, they can wear off if not fired properly, as we have discussed.

The optimum technique appears to be polishing ceramic restorations and not placing glaze and stain. The challenge with polishing is that technicians in general prefer to stain and glaze instead of polish, since polishing usually requires more time and effort, and the color of the restoration body cannot be changed. The laboratory profession knows of these challenges and technicians are attempting to remedy it.

What can you do to avoid this disagreeable challenge in your practice?

The easiest remedy is to send your technician accurate photos and written descriptions of the desired restoration colors. By doing so, the technician can have the body color of the restorations fabricated very close to the actual color of the teeth without adding stain and glaze.

Also, talk to your laboratory technicians and tell them of your challenge with degenerating color. Suggest that you will send more adequate photos and descriptions concerning color. Additionally, request that-whenever possible-the technician polish your restorations instead of staining and glazing them.

Summary

It is possible to reduce color degeneration of ceramic restorations. Use methods to make the original body color of the restorations as close to the desired color as possible, and reduce or eliminate staining and glazing. Polishing restorations instead of staining and glazing is recommended.

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD, is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah. He is the founder and director of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing-education organization initiated in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is a cofounder (with his wife, Dr. Rella Christensen) and CEO of Clinicians Report (formerly Clinical Research Associates).