'I could write a book …and I often do …'

by Jean A. Sagara and Arnold G. Rosen, DDS, MBA

Dr. Arnold Rosen shares his experiences with implant case management and dentist-to-laboratory communications.

When I recently asked my colleague, Dr. Arnold Rosen, if he would share his insights into the issue of dentist-to-laboratory communications, he said, "I could write a book ellipse and I often do in the course of managing a complex dental implant case."

This month, Dr. Rosen will discuss his experiences with implant case management, a subject with which he is very familiar. His experience draws on his clinical practice as a prosthodontist. He also recalls frustrations while teaching at Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, where he founded and ran its Dental Implant Center and was director of restorative services and the Tufts GPR Program.

Implant treatment is driven by the need to replace missing teeth. The restoring dentist is the architect of the treatment - or the quarterback - and, ultimately, is responsible for the success or failure of the plan. The patient's first day typically involves a discussion of implants as an option; the last day focuses on the completion of a replacement. So, the prosthodontist, or general dentist, identifies the need, reviews the plan with the surgeon or periodontist and the lab technician, and then develops a prescription for success.

Procedures, whether surgical or technical, are carried out by prescription. While it is true that each team member is responsible for understanding the prescription, agreeing to the plan, and delivering the desired result, it is the restoring dentist who is responsible for the outcome. The restoring dentist's productivity and income will be impacted by any technical failures or changes in the treatment plan. And, just as important, it is the patient who will feel the greatest impact from unrealized expectations and the increased cost of prolonged treatment.

There is no greater test of the concept of "outcomes and incomes" as part of total quality measurement in dentistry than the management of multidisciplinary care in placing implant-supported prostheses. Often, implant treatment requires tooth movement, extractions, root canal therapy, soft-tissue management, and preimplant surgery to provide a healthy environment for the implants. It is a complex program of care spanning six months to several years. Implant treatment tests our ability to plan; standardize, store, and share information; and maintain continuity of care. In the end, it tests our ability to optimize the outcome. Without doubt, the majority of this falls on the shoulders of the prosthodontist, or restoring dentist, who initiates and completes the process.

Imagine treatment that spans months or years and involves at least three parties - the restoring dentist, the oral surgeon or periodontist, and the dental technician. Often, additional specialists are required to join the team along the way. No wonder I think I could write a book on this subject!

But how could we condense the book, bind it, and place it somewhere that makes it easy to update? How could we make it accessible to all parties so that, collectively, we can improve outcomes and reduce opportunity costs (resulting from numerous phone calls, lost notes or reports, misplaced X-rays, and miscommunication)? I believe we can do it by standardizing the process of collecting information, by saving it in a digital format, and by networking. That is what compelled me to turn to the Internet a few years ago as a platform for improving case management through better communication.

Standard information transfer for implant treatment management often includes these steps:

- Communication with a laboratory to plan the restoration and estimate the cost

- Communication with an oral surgeon or periodontist to determine the feasibility of implant locations to support the restoration

- Identifying any additional preimplant surgical or specialty procedures

- Completing and sharing a treatment plan with caregivers and the patient

- Coordinating preimplant surgical procedures, if necessary

- Communicating design of a surgical stent, if required

- Coordinating restorative support at the time of surgery, if required

- Acquiring a surgical report indicating the type, size, and location of the implants and any variations from the original prescription

- Delivering or adjusting an interim prosthesis at the time of surgery or following surgery, if required

- Sequencing surgical and restorative procedures if im plants are placed in phases

- Maintaining the patient during the healing phases

- Determining required components based on the type, size, and location of the implants and prosthesis design

- Ordering components

- Coordinating fabrication and communicating with the network and lab

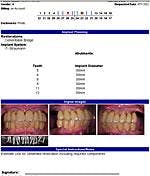

In my experience, these steps represent 14 potential points where things can go wrong without adequate communications. The process benefits from standardizing information flow, as well as from networking. Each clinician can use a notepad to collect information and then use a telephone to network. But is this efficient? Each phone call increases the opportunity cost, and every note puts sharing and access to information at greater risk. See Figure 1.

Our office uses computer forms to collect data, and then we use the Internet to network. We use commercially available, Web-based programs to generate, store, and share accurate and standardized prescriptions for planning and executing prosthesis fabrication. We also use a commercially available Web-based program that creates a virtual private network to store and disseminate all relevant data over the course of treatment, whether it is for six months or two years.

Even if we know what a computer form is, how many of us really understand what a network is and why the Internet is such a powerful network? Having spent the last few years learning about this myself, I'll offer some helpful definitions and analogies provided by others.

Miriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (Tenth Edition) defines networking as "ellipse the exchange and sharing of information or services among individuals, groups, or institutions." I would suggest that the largest network in the world is the telephone system. In reading Roger F. Pasquier's "Owl" from the Encyclopedia Americana Online, he provides some examples: "A good image of a network is that of a group of people talking to one another."

Seems pretty simple, doesn't it? Making the link from this group just chatting in an informal gathering, Mr. Pasquier then makes the link to technology networks in the way we understand the term today: "A computer that simply stands alone can be compared to a person stranded on a desert island. Even if that person is very well-equipped for survival, what she or he can do is severely limited compared with what is possible for a member of even a small society. A network-attached computer can potentially make available all the data on every other computer it can reach."

Herein lies the sublime potential for true networking in our modern world. Moreover, it is one that dentistry must optimize. Computers can colonize us; they can create communities of shared interests and objectives.

I am aware that much of this series has been dedicated to communications between a restoring dentist and a lab technician. In the case of implant dentistry, however, the universe of communications must be expanded to include the entire treatment team. During my years in a large institutional setting, I saw firsthand some of the limits to our case-management approach. It became obvious to me that we lacked the technology to provide easy access to all of the clinical information that ultimately would improve our productivity. All too often, phone calls for case discussions ended in a promise of a call-back. All too often, X-rays and reports were not available when required. All too often, reports were misplaced inadvertently. All too often, lab work was inefficiently managed. This was not the fault of individuals as much as it was due to the absence of a centrally organized, controlled, accessible clinical communications infrastructure. The Internet is changing all that.

The objective of networking is to effectively bring all parties together in one virtual place. Whether one room away or five states apart, the ease of access to critical information should be the same. The entire medical profession is beginning to appreciate this need. It seems axiomatic that with better communications, outcomes and incomes will improve.

The following case compelled me to move toward digital management to support the treatment process: One of my patients is a woman who travels between the Northeast and the Southeast with the change of seasons. After maintaining upper and lower fixed bridges on her fragile teeth, it was time for dentures or implant-supported fixed bridges. She was prepared for an extensive, time-consuming, and expensive treatment process. I made a digital, online book that my team of clinicians and I shared to successfully coordinate and manage treatment for this patient. Figure 2 shows the treatment-planning documents, referral forms, and images used for this online case-management approach.

Without the use of this digital book, our team could not have overcome the geographic-distance limitations nor the complexity of the case without serious inconvenience to the patient. Moreover, the potential to compromise quality of care would have increased. This digital book produced superior outcomes, not to mention a level of patient satisfaction that further validated our online approach.

Thank you, Dr. Rosen, for these reflections about the higher values available through digital networking. In the October issue, Dr. Rosen will offer practical guidance on how to use these technologies further. Specifically, he will share the forms used to collect data, the format used to store data, and the programs used to network data. Successful treatment, particularly in complex cases, requires a more innovative use of digital forms, digital images, and digital networking among the caregivers. Ironically, where once the telephone's "party line" yielded to the "private line" option, we now find ourselves with a need to combine the two - a private party line, as it were, for authorized users on a discrete, secure network - one that gives access to a common book of clinical data for clinicians who work as a team to treat the same case. The telephone is old technology, not just old-fashioned technology. It is not the primary networking tool it used to be. Though Lily Tomlin made us laugh at her, we said goodbye to Ernestine a long time ago.