Outcomes-based practice : Component search — picking your fights...Part 8

by David W. Chambers, EdM, MBA, PhD

Pat Dallas at FPG International

A critical distinction between evidence-based dentistry and outcomes-based practice is the difference between using data from somebody else's practice and using data of your own.

In dental practice, the Wisdom of Solomon is to find out how your practice works and make improvements on a constant basis. Don't wait for someone to hand you the clothes they look good in. It will be a long wait, and they probably won't fit anyway. Obviously, revelation and rented knowledge are pluses, but they are more likely to happen and make better sense to those dentists who understand their practices and are already hard at work improving them.

A tool chest of techniques for improving practice will make improvements go more smoothly. This one and the next four articles will describe simple procedures that can become habits for continuous improvement. Some of the techniques require little more than asking the right questions; the rest can be done with paper and pencil. None of them requires outside expertise or sophisticated statistical manipulations. After all, Solomon did not have a laptop.

Random approaches to improving one's practice continuously are almost as bad as none. If you ask your staff, they will tell you that the "fix de jour" has been a prescription for frustration. Resources are limited, so they should be applied with intelligence. The first part of the Wisdom of Solomon is to identify the problems most in need of being solved.

Level 0 Learning uses a simple rule for deciding what to work on — whatever is causing the most trouble at the moment. "Right now, I am frustrated with so and so. Today, I will take whatever steps are available to address this problem." This satisfies the need to appear in control and active in practice improvement. Reacting squanders resources and eventually dulls the appetite for change.

Level 1 Learning begins with the premise that the investment in improvements must be small. Since resources are limited, only small problems will be tackled. There is something to be said for this approach: It maximizes the probability of getting small results.

At Level 3, several tools can be used to identify the most appropriate targets for practice improvement. In this article, we will discuss three: Pareto graphs, "fishbone" diagrams, and the Five Whys. All of these approaches operate at the component level. They take things as they are, rather than looking for underlying factors.

Wilfredo Pareto was a 19th century Italian economist who discovered that a few people had most of the wealth and most people lived on limited means. He summarized this finding as a ratio. Yes, Pareto is the guy who invented the "80:20 Rule." The first step in practice improvement normally should be to distinguish the "vital few" components from the "interesting many." Find out which levers cause change in your practice and concentrate on controlling them.

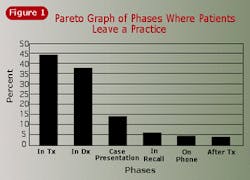

It has long been known in dental school clinics that patients are lost in the initial screening process. The X-ray department, the screening clinic, and others on the front end of patient intake are all flogged to show proper concern for this problem. But what about the likelihood of losing patients further along in the treatment sequence? Figure 1 shows the probability of a person leaving a dental clinic at each stage in the treatment process based on actual data in a clinic. Because this is a Pareto graph, the columns are arranged in descending order, rather than sequence of treatment. The total of all the columns is 100 percent. The height of the columns represents the number of patients leaving during that phase of treatment divided by the number of patients entering that phase. In absolute terms, there are a lot of patients who drop out during screening, but relative to the patients available at each point, the greatest likelihood of failing to retain patients is during treatment. The Pareto graph has shifted our focus on how to make a better dental practice from patient intake to patient retention.

Try this project: Every time an appointment takes longer than anticipated, note the reason on the bottom of the billing or reappointment form sent to the front desk, using a code of your own devising. For example: procedure more difficult than anticipated, dentist engaged in socializing with patients, difficult or demanding patient, equipment or materials not available, etc. The front-desk staff will tally these at the end of the month and find the percentage in each category. These are then arranged on a graph beginning with the factor causing the largest percentage of overruns down to the factors causing the least. The best improvement in office efficiency is likely to come from addressing the most common problems, not the least common.

Practitioners must recognize the distinction between performing this project and what journal articles may relate about lost patient statistics. Both your study and the one you read about can be presumed to be true, but only one of them applies directly to you. Literature or feedback during a continuing-education course may give you insight and help you understand what might your situation may be. A critical distinction between evidence-based dentistry and outcomes-based practice is the difference between using data from somebody else's practice and using your own data.

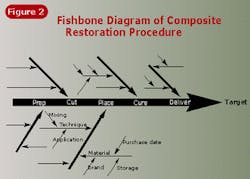

Another approach to identifying promising targets for practice improvement relies on expert judgment (yours). No data need be collected. This is called the "fishbone" technique, because of the kind of diagram created (see Figure 2). The backbone of the diagram is the sequence of major activities in a procedure. Let's assume, for example, that the steps in a composite restoration include preparing the field, cutting the preparation, placing materials, curing them, and then delivering the final product. These steps are arranged in sequence along the backbone of the diagram.

A diagonal arrow is placed pointing to each of the steps. The arrow represents the ideal circumstances for performing the task. The arrows coming sideways into these diagonals are the conditions that could impact proper task performance. If we look only at material placement, some of the candidates might include the material itself and its placement. For these factors, there are other conditions for success. For the material, we could consider selection, storage, and freshness. Handling might include preplacement considerations, such as mixing, and placement considerations, such as size and application technique. The latter are the small "bones" at the tips of the diagram.

Oftentimes, just thinking through in a logical fashion the conditions necessary for success at each step of a procedure will reveal uncertainties that are good candidates for investigation. This is a marvelous team exercise, because it ensures that every office member involved understands the steps and their importance for each procedure. Sometimes the group activity uncovers misconceptions and ambiguous processes within the office.

It is not important that the fishbone in one dental office is identical to the fishbone in another. There are few universal and invariant procedures in dentistry. It is essential, however, that all team members within an office know the fishbone for each procedure perfectly and that every detail of it is well-understood. The fuzzy areas are the ones that should be explored for continuous practice improvement.

There is an on-the-go, informal way of doing the "fishbone technique" that can become a useful mindset for improvement. It is called the "Five Whys" technique. When something goes in an unexpected manner, ask why — and don't stop until you have done it five times. The first time we ask why, we often get a superficial understanding or little more than a description of the problem. The second time we ask why, we are likely to get an explanation of what was going on when the problem occurred. Next, we get an explanation of what we were doing when the problem occurred. Gradually paring away the layers of explanation reveals the core cause of the problem.

Consider the following example. The office manager might confront the claims secretary about a customer who wrote a complaining letter. The response to the first why is, "Because her inquiry about a refund was poorly handled." The second why ("Why was the inquiry muffed?") produces, "Because we confused one patient with another." This may be an accurate answer, but still is not very useful. A third why is needed: "Why did we confuse this Mrs. Andrapoupolos with the other Mrs. Andrapoupolos?" "Because the computer field for 'name' only has a limited number of characters, there was not enough room to put in a differentiating first name." This situation requires yet another why question. Eventually, the office manager will understand the problem in sufficient detail to fix it. The purpose of repeating the why question is to move from a CYA response or explanation to a cause that can be corrected.