Annuities — free lunch?

For more on this topic, go to www.dentaleconomics.com and search using the following key words: annuities, investments, equity indexed annuity, National Association of Securities Dealers, insurance, index change, index method, S&P 500.

by Rick Willeford, MBA, CPA, CFP

"Doctor, are you tired of losing money in the market?" begins the opening pitch. "What if I told you I had an investment that would give you some of the upside potential of the stock market but guarantee that you could not lose money?" Does this sound too good to be true? Then read on.

The investment turns out to be an "equity indexed annuity," or EIA. The pitch sounds tempting, especially as the stock market goes through one of its periodic tumultuous periods. Perhaps it's too tempting. The National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD, which regulates broker-dealers) is so concerned that the product is being over-hyped and oversold that it issued an Investor Alert in June 2005. So, what's the rest of the story?

First, here's some background on annuities. In their simplest form, you used to give an insurance company a sum of money in exchange for their giving you a guaranteed monthly check for the rest of your life. The beauty was that you couldn't outlive your money. But part of the price you paid for that guarantee was that the returns were pretty stodgy.

Annuities have come a long way since that basic model. Nowadays many people start investing every year, like any other savings plan. Part of the allure is that the investments grow tax-free. (A more appropriate term is "tax deferred." You pay ordinary taxes when you withdraw the money later, like with a retirement plan.) Being a good red-blooded American (and smart dentist, to boot), you're probably not satisfied with your father's fixed-return annuity. So the insurance company will let you spice things up by letting you invest your annuity money in mutual funds, with the hope of a higher return. These are called variable annuities, vs. the more conservative fixed annuities.

As with variable life insurance products, both you and the insurance companies should be happier. You, because you hope to make more money with mutual funds, and the insurance company, because they are not obligated to promise you a specific return. That's your responsibility.

So where"s the rub? For one thing, the terms are so complicated that most salesmen, er, "financial planners," do not really understand the product. For another, the details are in the fine print, and we warn clients that there is rarely any good news in the fine print. Let me give you enough information to at least suspect some of the issues. I apologize in advance for some of the "techno-speak."

First, let's look at the guaranteed minimum return, which is typically around 3 percent, less than a U.S. Treasury security with the same maturity. You may ask, 3 percent of what? Believe it or not, it may be 3 percent of only a portion of the amount invested (such as the surrender value). Also, the 3 percent may not be compound interest, and the contract may require you to hold the product for 15 years to get credit for any interest! Or it may require you to actually "annuitize" the contract (e.g., convert into lifetime payments) rather than just withdraw your money. The problem is that 97 percent of all annuities never get annuitized. They get cashed in instead. Read the fine print!

Second, it takes a combination of a finance degree and a legal background to understand the "equity indexing" part, which lets you participate in some of the upside gains in the stock market. The annuity value is linked in various ways to the change in the level of a stock price index ("index change"), like the S&P 500 Index.

The first gotcha is the phrase "index change." When you think of the S&P Index growing at an average historical rate of around 10 percent per year, the "total return" includes dividends. The annuity excludes the impact of dividends because the annuity contract literally means just the "change" counts, and this immediately reduces the potential "return" by about 20 percent!

The annuity does not normally give you credit for 100 percent of the index change. Instead, the annuity specifies a "participation rate," normally between 50 to 90 percent of the change. After the gross change is multiplied by the participation rate, then the annuity may subtract a set "spread" that may be as much as 3 percent, then you get credited with the rest. So if the gross change is 10 percent for a year (vs. 12 percent if dividends had been included), the participation rate is 70 percent, and the spread is 3 percent, then you only get credit for 10 percent x 70 percent = 7 percent – 3 percent = 4 percent. That"s a far cry from the total return of 12 percent!

There is often a cap of 1 percent per month (12 percent per year) that limits the amount of change that can be counted. This has an insidious effect because the average long run return from stocks is heavily influenced by years with abnormally high returns. Not only does the annuity slash the effective return that is allowed, it also severely limits your upside potential returns in good years.

Finally, what "index method" is used to determine when and how the index change itself is measured? A simple approach is to look at the annual change at the end of each year. If there was a positive change, then the index is reset at that higher level for measuring the next year. An alternative approach is called the "monthly average return method." This measures the increase in the index level from the beginning of the year to the average month-end level during the year. Suppose the index started at 1,000 and rose 100 points each month. At the end of 12 months, the level would be 2,200. However the average level for the year is 1,600, so the change for calculation purposes is 600.

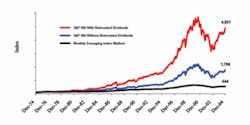

So there is a complex interaction of the participation rate, spreads, caps, and index method. You can bet that the odds are stacked in favor of the insurance company, in spite of the handsome marketing material. The graph above is from the Virginia-based Securities Litigation and Consulting Group. It shows the impact of the monthly averaging method on the calculation of index changes from 1975 to 2004.

The top line shows the value of the S&P 500 over time with reinvested dividends. The second line excludes dividends, and that reduces the return over the period by 64 percent! The lowest line then shows that the monthly averaging method further reduces the change in the price level of the index by another 70 percent over 30 years! The investor is in for quite a disappointment if he or she thinks the annuity is going to let him or her "participate in the upside" and give credit for the full increase to 4,921 vs. just 544!

The net effect is that you pay dearly for a paltry downside guarantee, and you may realize as little as 20 percent of the upside potential after the smoke clears. We didn"t even look at the tax disadvantages. (Your contributions are not deductible, your income is subject to ordinary tax rates vs. capital gains, and your heirs have to pay income taxes on any remaining income vs. a step up in basis at death.) Also, your funds are not liquid because you have to pay a surrender fee if you touch the money before seven to 10 years.

So, what is the alternative? The answer is to use a balanced portfolio of low cost, no-load mutual funds. Consider the following:

- Since 1926, the average return on a portfolio containing 60 percent S&P 500 and 40 percent Treasury notes has never been negative during any 10-year period.

- The lowest annual return on such a 60/40 balanced portfolio was 2.64 percent, and that was for 1929 to 1938, a period in the Great Depression.

- The average 10-year return on a 60/40 balanced portfolio has been 9.28 percent.

So, for the longer horizons necessary to avoid EIA surrender fees, a balanced portfolio provides similar downside protection with a significant increase in the true upside potential. Your money is liquid and you enjoy long-term capital gains rates, plus a step up in basis for your heirs.

Uncle Cletus always said, "You can put lipstick on a pig … but it is still a pig!" I suggest that you pass on this expensive pig and let somebody else get slaughtered!

Raymond "Rick" Willeford, MBA, CPA, CFP®, is president of The Willeford Group, CPA, PC, and Willeford CPA Wealth Advisors, LLC. As a fee-only advisor, he has specialized in providing financial, tax, and transition strategies for dentists since 1975. Willeford is the president of the Academy of Dental CPAs, a consultant member of AADPA, and is available as a speaker nationwide. Contact him by phone at (770) 552-8500, or by e-mail at [email protected].