Beyond the drill: Creating connections through empathy in dentistry

Key Takeaways

-

Empathy reduces dental anxiety. Building emotional connections through verbal and non-verbal communication helps patients feel heard, safe, and more receptive to care.

-

Every team member plays a role. From the front desk to the operatory, empathetic communication at each patient touchpoint strengthens trust and improves the overall experience.

-

Patient-centered care drives better outcomes. Involving patients in their treatment, using simple explanations and visual aids, and practicing active listening all contribute to stronger relationships and more successful care.

People often feel anxious when they go to the dentist, often due to a traumatic childhood experience or general dental anxiety. This fear can lead patients to delay care, resulting in neglected and worsening oral health issues. Implementing empathy in dental practices is essential to addressing these concerns. By building emotional connections with patients, dental professionals can ease anxieties and promote trust.

This article explores the critical role of empathy in dentistry and offers practical strategies for dental professionals to strengthen patient relationships and improve treatment outcomes. Clinics can foster a more patient-centered environment by providing empathy-focused training for the entire dental team—from the front desk to the dentist. This approach can reduce patient anxiety, increase treatment acceptance, and lead to more seamless appointments. The ultimate goal is to equip dental teams to create a welcoming, low-stress atmosphere that builds long-term trust and promotes lifelong oral health.

Introduction

Empathy is defined as the ability to share someone else's feelings or experiences by imagining what it would be like to be in their situation.¹ This concept is essential when addressing dental fear, which is the anticipation of danger that causes intense discomfort.² Understanding both empathy and fear creates a strong foundation for building meaningful connections between dental teams and patients.

Dental fear is one of the most common concerns in dental settings and often causes behavioral changes. Anxiety can heighten patients’ pain perception,³,⁴ making the experience more difficult for everyone involved.⁵,⁶ To help reduce this anxiety, practices must foster a supportive, calming atmosphere. Every member of the dental team plays a role in creating that environment, and empathy is a key part of communication—both verbal and non-verbal.⁷

Effective communication ensures patients understand their diagnosis, treatment options, and overall care experience.⁸ This, in turn, helps form strong, lasting bonds with patients.

Essence of care team/patient communication

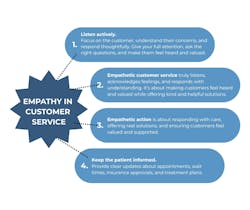

The process of empathetic communication, as shown in Figure 1, begins with the patient’s first point of contact—whether by phone or in person. Front desk staff play a pivotal role in creating a positive first impression, and courtesy—defined as respectful, polished behavior—is essential in this position.⁹

Although this article focuses on communication between patients and dentists, experience shows that daily interactions with the front desk and other team members often lay the groundwork for long-term trust.

The second point of contact may be the dental assistant or hygienist, depending on practice flow. Dental assistants often begin charting or gathering patient concerns before the dentist enters the room. This interaction is a valuable opportunity to listen actively and help calm any nerves.

If the hygienist is the next point of contact, they also need to connect empathetically. Whether the patient is anxious, refuses X-rays, or arrives upset from a past negative experience, empathy is essential. Pediatric patients present another challenge—building rapport with a scared, crying child requires patience, emotional awareness, and confidence.

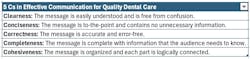

Table 1 summarizes key communication principles that help dental professionals engage effectively with patients.10

Strategies for daily implementation

-

Maintain team connection.

The entire oral care team should be aligned. Daily morning meetings help foster communication and ensure that every team member understands the patient journey. Team-based empathy supports the patient's experience from check-in to checkout. -

Use empathy in all communication.

Verbal and non-verbal cues matter. Eye contact, tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language all shape how a message is received. If a patient refuses X-rays, try to understand their concern—it may be fear, discomfort, or cost-related. Respond with empathy, not judgment. -

Use simple language and visual aids.

When explaining treatment plans, avoid complex jargon. Visual aids—such as images or typodont models—can enhance understanding and cooperation, especially for patients with unique needs.11-13 -

Involve the patient in their care.

Use a patient-centered approach by helping individuals understand their condition and participate in decisions. For example, if a patient has cavities, explain contributing factors and offer preventive guidance. Research supports shared decision-making and personalized care as pillars of effective dentistry.14,15

Conclusion

This article highlights the importance of strong communication and emotional intelligence in dentistry. Practicing empathy—within the team and with patients—helps reduce stress and foster deeper trust. Maintaining open communication, listening actively, and responding with empathy strengthens both the care environment and the patient experience. Confidence and kindness, practiced consistently, are powerful tools for creating connection and improving outcomes.

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in DE Weekend, the newsletter that will elevate your Sunday mornings with practical and innovative practice management and clinical content from experts across the field. Subscribe here.

References

-

Cambridge University Press. Empathy. Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary.

-

Merriam-Webster. Fear. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fear. Accessed March 17, 2025.

-

Weisenberg M, Aviram O, Wolf Y, Raphaeli N. Relevant and irrelevant anxiety in the reaction to pain. Pain. 1984;20(4):371–383. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(84)90114-3

-

Al Absi M, Rokke PD. Can anxiety help us tolerate pain? Pain. 1991;46(1):43–51. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(91)90032-S

-

Moore R, Brødsgaard I. Dentists’ perceived stress and its relation to perceptions about anxious patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(1):73–80.

-

Brahm CO, Lundgren J, Carlsson SG, et al. Dentists’ views on fearful patients: Problems and promises. Swed Dent J. 2012;36(2):79–89.

-

Ho CY, Chai H, Lo EC, Huang Z, Chu CH. Dentist-patient communication in quality dental care. Front Oral Health. 2024.

-

Ho CY, Chai H, Lo EC, Huang Z, Chu CH. Dentist-patient communication in quality dental care. Front Oral Health. 2024.

-

Merriam-Webster. Courtesy. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/courtesy. Accessed March 17, 2025.

-

Singfield A. The Five C’s of Effective Communication. Vista Projects. https://www.vistaprojects.com/effective-communication/. Accessed June 18, 2024.

-

Nilchian F, Shakibaei F, Jarah ZT. Evaluation of visual pedagogy in dental check-ups and preventive practices among 6-12-year-old children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(3):858–864. doi:10.1007/s10803-016-2998-8

-

Orellana LM, Martínez-Sanchis S, Silvestre FJ. Training adults and children with an autism spectrum disorder to be compliant with a clinical dental assessment using a TEACCH-based approach. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):776–785. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1930-8

-

Mah JW, Tsang P. Visual schedule system in dental care for patients with autism: A pilot study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;40(5):393–399. doi:10.17796/1053-4628-40.5.393

-

Apelian N, Vergnes JN, Bedos C. Humanizing clinical dentistry through a person-centred model. Int J Whole Person Care. 2014;1(2). doi:10.26443/ijwpc.v1i2.2

-

Vergnes JN, Apelian N, Bedos C. What about narrative dentistry? J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(6):398–401. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2015.01.020

About the Author

Ana Rodriguez Arias, CRDH

Ana Rodriguez Arias, CRDH, is a Venezuelan-trained dentist who graduated in 2010, ranking 20th in a class of over 200 students. She completed a postgraduate program in orthodontics in Argentina from 2012 to 2014 before relocating to Florida, where she has worked in the dental field since. After gaining experience as an orthodontic assistant, Ana has been practicing as a certified registered dental hygienist in private practice since 2020. She is currently an active candidate for an advanced education in general dentistry (AEGD) program as part of her pathway to obtaining US licensure. Contact Ana at [email protected].

Tifany Moncada

Tifany Moncada is an aspiring dentist with over four years of experience in dental practices, encompassing both administrative duties and direct patient care. She earned her degree in microbiology from the University of Florida and is actively pursuing a career in dentistry. Tifany has worked closely with patients to present treatment plans, assist during clinical procedures, and support daily office operations—gaining a well-rounded foundation in dental care and practice management. Contact Tifany at [email protected].