Solving zirconia crown challenges

What you'll learn in this article

- Why zirconia crowns often present with open margins, lack of occlusal contact, and weak interproximal contacts—and how both dentist and lab technician roles contribute to these challenges

- How to select appropriate cements, such as resin-modified or conventional glass ionomer, to help mitigate open margins and improve long-term retention

- What causes post-op occlusal problems and esthetic mismatch, including superficial staining techniques and poorly adjusted crown anatomy—and how to prevent these complications

- Why careful attention to prep scanning, communication with labs, and final occlusal adjustment is essential to avoid rough contacts, cusp fractures, patient discomfort, and TMD symptoms with zirconia crowns

Each month, Dr. Gordon Christensen answers a question from readers about everyday dentistry.

Q: I have been placing zirconia crowns made by several different laboratories for over 10 years. Overall, they are working acceptably, but I see several issues that bother me. I have not seen these issues previously on cast-gold alloy crowns or porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns. The following challenges are present in some or all of the zirconia crowns I have seated:

- The margins are open to the naked eye.

- After seating, cement is clearly visible on the margins.

- When seated, most do not contact opposing teeth.

- Even when the crowned teeth have extruded weeks or months later, they contact opposing teeth only in a few locations.

- I have occasionally had a tooth adjacent to the new crown break off a cusp, apparently related to the lacking occlusal contact of the new crown.

- Although crown color at seating is usually acceptable, only a few months or years later the color no longer matches.

- Often contact areas are rough. Some still have the milling lines on the contacts.

- Frequently, the contact areas are light or even open, requiring the addition of ceramic to make adequate contact areas with the adjacent tooth.

- Infrequently when seating multiple zirconia crowns on patients, I have had them complain postoperatively about headaches or even TMD until definitive occlusal equilibration is done.

Should I be concerned about these issues, or is what I have described the state-of-the-art for current crowns that is not going to change?

A: I appreciate your expression of the challenges you’ve seen with zirconia crowns in your practice. These issues are not uncommon. On a positive note, most of them have solutions. They require both laboratory technicians and dentists to communicate, and each must make changes in their activity to reduce or eliminate issues.

I will share my empirical experience as well as scientific evidence on each of the problems you have observed.

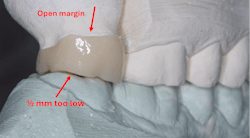

Open margins

All margins, current or historical, are open to a microscope. You are correct—the current margins are more open than those on previous crowns. The virtual dies of today are spaced 30 microns or more on the axial walls to 500 microns on the occlusal surfaces. Historically, the spacing was one layer of model airplane dope on the die except for the margins. The virtual die spacing of today usually spaces over the crown margins, resulting in an addition to the already open margins made by scanning and milling machines. Scanners are improving and AI will help mediate this challenge.

Visible cement line

The naked eye can usually see a cement line. To remedy the caries potential on the open margins as described, use of a cariostatic cement is strongly advised. Resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) (3M RelyX Luting or FujiCEM Evolve) or conventional glass ionomer (GI) (GC Fuji 1 or 3M Ketac Cem or other brands) are the preferred cements. Both types of cements release fluoride and can somewhat compensate for the open margins (figure 1). In the 1970s and ’80s, GI cement was popular. Almost no crowns came off in service when this rigid, cariostatic cement was used. In recent in vivo research by Clinicians Report Foundation (CR), fewer RMGI cemented crowns have come off in service than those cemented with resin cement. Use RMGI or GI for cementing zirconia crowns. The fluoride is essential, and fewer crowns will come off in service.

No occlusal contact when seated

Because labs are making zirconia crowns without occlusal contact (about 0.5 microns short of contact with the opposing arch), the teeth on both sides of a new crown must take the occlusal load until the crowned teeth and the opposing teeth extrude into contact (figure 1). It is understandable why labs are making the crowns short of occlusion—finishing and polishing sintered zirconia is difficult and time-consuming for the clinician if the crown is too high. This concept is probably not of major concern for a typical single crown, but it may be a challenge for multiple tooth restorations where a significant portion of the occlusion is affected.

When noncontacting teeth have extruded into contact, only slight occlusal contact with opposing teeth is present

There are cloud-based dental anatomy libraries from which dental technicians select the appropriate anatomy for zirconia crowns. Until continuing research develops appropriate computer programs and AI is used to select which crown anatomy from the cloud is right for a specific clinical situation, this issue will continue to be present. Is it serious? Maybe.

When teeth extrude, weeks or months are needed until the crowned tooth and the opposing tooth or restoration can eventually move and find the best interdigitation. Obviously, this could influence the patient’s occlusion significantly.

Research is underway to improve this challenge.

Occasionally a cusp on the tooth adjacent to a new zirconia crown breaks off

With zirconia crowns being made short of occlusion and the adjacent teeth taking the load, an interim occlusal overload on adjacent teeth can be expected. The occlusion must move to accommodate the new occlusal contacts. If the adjacent teeth are weak, a tooth cusp or restoration can break. I have had this occur a few times. I suggest careful adjustment of teeth or restorations adjacent to new zirconia crowns to reduce this challenge.

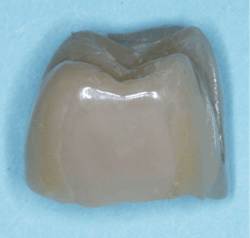

Color of crown becomes unacceptable after a short time

Why is this occurring? Many technicians are using superficially applied color in glazes on zirconia crowns to improve the color match with adjacent teeth. CR has shown with in vitro studies that this superficial color and glaze soon wear off (figure 2).

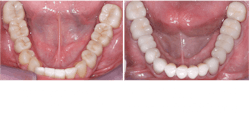

Many laboratory technicians are overcoming this challenge by staining zirconia crowns at the presintered (green) stage. Stains are placed on this porous form of the zirconia. As the crown is heated (sintered), the stains integrate into the body of the zirconia, and the color changes to whatever the technician prefers. This technique requires the technician to have significant knowledge about color and how and where to apply the stains. This technique is rapidly being implemented to make the unpredictable zirconia colors match teeth better (figure 3).

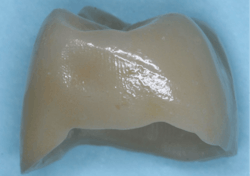

Contact areas on the crown are rough

This is usually a dentist-caused problem. Almost all crown preps are scanned by the dentist, a staff member, or the lab tech scanning the polymer impression. If the contact areas of the teeth adjacent to the crown are rough, the contact areas of the crown will probably be rough. The dentist should smooth the contact areas of teeth or restoration contact areas before making an impression of the prep.

There is also a lab problem. Sometimes the machine milling lines are left on the contact areas of zirconia crowns. Techs should set the milling device to make the contact areas slightly tight. I suggest at least about half the thickness of a human hair (about 25 microns). This allows the tech to finish and polish the milling lines on the new crown (figure 4).

Contact areas are light or often need ceramic addition

This issue is also a dentist problem. The adjacent teeth do not move during an impression, whether it is polymer or a scan. If the adjacent teeth have been treated for periodontal disease and are slightly mobile, the dentist should inform the technician to make the contact areas slightly tight. Again, I suggest at least half the thickness of a human hair (about 25 microns). Historically, this was done by slightly scraping the stone on the contact areas of the adjacent teeth.

Headaches and TMD

Some of the previous issues can be responsible for occlusal changes in the mouth. Occlusal premature contacts are unavoidable, including changes in incisal guidance and working and nonworking interferences. Zirconia does not wear significantly, and occlusion will not wear enough to reduce the premature contacts. It is the dentist’s responsibility to adjust the patient’s occlusion when putting any restorations in the mouth, especially zirconia crowns.

Summary

Zirconia has dominated fixed restorations over the past 10 years. It has a wonderful potential for the future. However, numerous challenges still exist related to the digital changes now present in the profession and dental materials. Continuing research and development of new zirconia varieties and cements are coming and will enhance zirconia restorative dentistry. In the meantime, dentists and laboratory technicians need to discuss the challenges reported in this article and make decisions about how to reduce or eliminate them.

Further reading: Improving the color match of zirconia crowns

Editor's note: This article appeared in the July/August 2025 print edition of Dental Economics magazine. Dentists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

About the Author

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD, is founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses and cofounder of Clinicians Report. His wife, Rella Christensen, PhD, is the cofounder. PCC is an international dental continuing education organization founded in 1981. Dr. Christensen is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah.