Is your intraoral camera a diagnostic tool or a marketing tool?

Since the time when intraoral cameras were first developed for use in dentistry, they have been promoted as tools for patient communication. We have been told that they help patients understand the need for treatment and thus improve case acceptance.1 But there is a risk in looking at intraoral cameras that way. Let me suggest a subtle but very important shift in your thinking on how you use this tool and how you present it to your patients.

When you say that you are using your intraoral camera as a communication tool, what you really mean is a sales or marketing tool. That’s my area of expertise. I’m a former practicing dentist turned marketing professional, so I have a unique perspective on this issue. Let me share some marketing principles to help you understand how to best use your intraoral camera.

One of my favorite dental marketing consultants and writers has been Suzanne Boswell, author of a landmark book on dental marketing, The Mystery Patient’s Guide to Gaining & Retaining Patients (PennWell Books, 1997).2What I like about her is that she bases her recommendations on well-done surveys and focus groups, not just feel-good marketing instincts. In this book she teaches that there is a disconnect in how dentists perceive the treatment acceptance process, in that they greatly overestimate the role of patients’ understandings of the need for treatment and greatly underestimate how much they rely on trust.

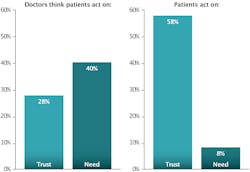

In one of her surveys, Boswell asked both dentists and patients on what basis patients accepted treatment plan recommendations. Out of multiple factors, dentists said the number one factor was the patient’s perception of need. Second was the trust they had in the dentist’s recommendations. But when patients responded, they said that the number one factor was trust—by a factor of seven to one—over their perception of the need (figure 1).2

Here’s my background on this issue. The bulk of my current business involves creating websites for dentists. I have learned that we get the best results for our clients when we tone down the “pushiness” of the content and focus instead on cultivating a feeling of trust in the website visitor. When we have done this, we have sometimes seen a dramatic increase in the conversion rate of a website. The same principle is at work in your use of your intraoral camera. Your patients are sensitive to subtle signals that tell them whether or not they can trust you. If you send them the wrong signals, it will undermine their trust in you.

Let me develop this point with a personal experience. When I started my practice, I was fresh out of dental school, deeply in debt, and really hungry for patients and work. If I had a patient who needed major treatment, I would honestly explain the need. I had a pretty good treatment plan acceptance rate, but I had enough rejections that it bothered me. Several years later, when I was fully busy, one day it dawned on me that it had become rare for a patient to turn down any treatment recommendation I made. I came to realize that while I hadn’t made any conscious change to my treatment plan presentation, there was definitely a change in my mindset. Instead of my thinking, “Oh, I really need you to do these crowns because I really need the money,” I was thinking, “It doesn’t really matter to me personally whether you do this or not.” It became clear to me that back when I started my practice, some patients were reading my neediness through my body language or my tone of voice. When that neediness was gone, their trust in me went up. With increased trust I experienced a higher treatment plan acceptance rate.

You can get a similar reaction depending on how you are using your intraoral camera. If you present this to your patients as a “communication tool,” there are cynics in your practice who will translate “communication tool” as “sales gimmick.” And if we were to probe the subconscious minds of our patients, we would discover that there are many more silent cynics than we realize. Moreover, even if you don’t overtly present it in this way, if that is what you are thinking, some of your patients will read that in your tone of voice or body language. This is the paradox of dental marketing—the harder you push, the less you are perceived as being trustworthy. The more professional and less sales-oriented your demeanor, the more credibility you will have with your patients.

If you bring up the subject of overtreating by dentists in social situations, it isn’t hard to find people who feel that this has happened to them—not necessarily with intraoral cameras, but just in general. These stories feed the fear people have of being “sold” work that they don’t need. And this is the problem you’re going to run into if you consider the intraoral camera to be a communication tool. If patients sense that you are using this to try to talk them into getting a crown, it’s going to eat away at the trust you need in your relationship. Let me suggest a better way.

To me, in my practice, the intraoral camera was always a diagnostic tool, and I would introduce it that way. The diagnostic advantages were clear. I could see a tooth from any angle I wanted—and under bright light, magnified 100 times.3 I could discover broken-down fillings and cracks in teeth that I couldn’t otherwise see. During an exam, I would scan the teeth carefully with the camera, talking to my hygienist about what we saw on the monitor while she took notes. The patient, of course, would overhear all these comments about leaky fillings or cracks in the teeth, and I would show them the pictures later. But I never wanted to present the intraoral camera as a tool “to help you see.” It was a tool “to help me see.”

Here’s a key marketing principle that you need to understand, not only in your use of the intraoral camera but throughout your practice, your website, and all your marketing. Trust is important in any marketing, but especially so in dentistry. When people need medical treatment, they usually have symptoms. But you may have a patient who comes in for an exam not knowing anything is wrong, and you have to tell them they need periodontal treatment and three crowns. This is in a context where they had a friend who had a dentist who told them they needed a bunch of work, but when they went for a second opinion they only had one cavity. Or maybe they vaguely remember reading the Reader’s Digest article years ago, “How Dentists Rip Us Off.”4

Suzanne Boswell has discussed this issue in articles and in her aforementioned book. She says, “A common focus group comment is, ‘I want to go to someone who cares more about me than the money.’”5 Whether consciously or unconsciously, they are looking for signals that will tell them whether or not they can trust you. These signals can be subtle, as illustrated by my own experiences in the early days of my practice.

Let me tell you a website story to drive this point home. Three years ago, one of our clients wanted us to create a little box on his website to capture visitor email addresses. It would offer people the opportunity to sign up for information and specials. Knowing dental marketing psychology as we do, we advised against it, but the client was insistent that he wanted to at least try it. He could gather the email addresses and then email the visitors who left the website without making an appointment to try to recapture them. OK, we told him, but let us run an experiment with it, which he agreed to. We put up the box and took it down in alternate months for the better part of a year. Not wanting to have it be an annoying pop-up window, we had it appear out of the way on the far-left side of the web page. When we analyzed his metrics at the end of the experiment, we discovered two interesting things. One was that people apparently didn’t find the box annoying, because it didn’t increase his bounce rate. But it did depress phone calls to the practice by 30% whenever it was up.6 People, whether consciously or unconsciously, read his intentions and they took this moderately aggressive marketing stance as a signal that this dentist might be one who cared more about the money than the patient.

We have found that trust is the best “sales” strategy in dentistry. If you tell people what they need and tell it honestly, most people will be able to sense your sincerity and you won’t need any gimmicks. Use the intraoral camera honestly as a diagnostic tool, and patients will accept your treatment recommendations. Then you can show them the pictures of their teeth and they will appreciate it. But realize that they’re going to accept your treatment plan not because they now understand dental materials, all the mechanics of the stresses on teeth, and the physiology of decay, but because they trust you.

References

1. Neuman KA. Maximizing the Use of an Intraoral Camera. Dentistry Today. July, 2003;22

2. Boswell S. The Mystery Patient’s Guide to Gaining & Retaining Patients. Tulsa, OK: PennWell Books; 1997, p. 137.

3. Intraoral camera. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intraoral_camera. Accessed November 8, 2019.

4. Ecenbarger W. How dentists rip us off. Reader’s Digest. February 1997.

5. Boswell, ibid., p. 123.

6. Hall DA. How Pop-Ups Can Hurt Your Dental Website. Infinity Dental Web website. https://www.infinitydentalweb.com/blog/popups-hurt-your-dental-website/. Published December 12, 2016. Accessed November 14, 2019.

David A. Hall, DDS, AAACD, graduated with honors from the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry and ran a private practice in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for many years. In 1995, he launched a website promoting his own dental practice. After requests from other dentists for help with their websites, in 2009 he founded Infinity Dental Web, a marketing agency that does digital marketing for dentists. He may be contacted at (480) 273-8888.

About the Author

David A. Hall, DDS, AAACD

DAVID A. HALL, DDS, AAACD, graduated with honors from the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry and ran a private practice in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for many years. In 1995, he launched a website promoting his own dental practice. After requests from other dentists for help with their websites, he founded Infinity Dental Web in 2009, a marketing agency that does digital marketing for dentists. Dr. Hall may be contacted at (480) 273-8888.