Dr. Robert Lowe discusses dental cements

Dr. Dalin: Bob, I have known you for a number of years and realize how much you like to share good, useful information with dentists across the country. I thought we should discuss something that has grown exponentially through the years ... dental cements. What started years ago as zinc phosphate and silicate cements has grown to a much larger list. Can you provide a brief summary of the many different categories of cements? Off the top of my head, I can think of zinc phosphate, polycarboxylate, silicate, glass ionomer, resin ionomer hybrid, and resin cement.

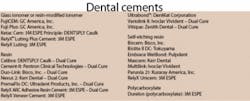

Dr. Lowe: Dental cements, like many of the current restorative products, have indeed evolved and changed a great deal in the 20-plus years that I have practiced dentistry. Silicate cements were a little before my time. But when I graduated from dental school in the early ’80s, there were two choices for the cementation of indirect dental restorative materials: zinc phosphate cement and polycarboxylate cement. Zinc phosphate was the standard for many years. It is important to remember that these materials really don’t “cement” or chemically bond to restorative materials. They are luting agents meant to fill the microscopic gap between restorative materials and tooth structure. Zinc phosphate cements, while used universally for many years, are soluble in oral fluids and can wash out when restorative materials are not engineered to fit precisely. Polycarboxylate cements have a slight advantage in that they chelate to dentin, but the film thickness is greater than that of zinc phosphate cements. Occasionally, this increased thickness can prevent a restoration from seating fully. Glass ionomer cements, which are still widely used as luting cements, offer some distinct advantages as compared to both zinc phosphates and polycarboxylates. The film of glass ionomers is extremely thin. In addition, they possess a fluoride release that has been shown to remineralize dentin. However, glass ionomers are still quite soluble in oral fluids. The next generation of cements evolved into modified resin ionomers. These cements have many of the advantages of glass ionomers but are much less soluble in the oral environment. In fact, some manufacturers report zero solubility with these materials. Once again, the one common thread with all of these types of cements is they do not bond to the restorative materials. The resin cement family evolved from the total etch and dentin adhesive technologies. For proper use, they require pretreatment of the tooth surface with 37 percent phosphoric acid and application of a dentin bonding agent prior to application of the resin cement. These cements truly form a micromechanical bond to both tooth structure on one side and restorative material on the other. Also, they are insoluble in oral fluids. Self-etching resin cements are the latest advancement in resin cements. They require no pretreatment of the tooth surface, and appear to have many advantages of resin cement systems - along with the ease of use of more traditional types of cements. It is important to emphasize that the bond strengths of self-etching resin cements are not as high as those for resin cements using the “total-etch technique.” But keep in mind that the job of any cement is to fill the restorative gap, not retain the restoration. Proper resistance and retention of the preparation is still important for the successful retention of any restorative material.

Dr. Dalin:Now that you have provided a great capsule review of each family of cement, let’s talk about specific recommendations by type of restoration. First, let’s take a look at metal or porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns. What do you recommend?

Dr. Lowe:Metal crowns, or PFMs, are still most easily luted using traditional cements. Since there is minimal ability to bond to metal with the exception of the four-meta type of cement systems, there is little advantage to using resin cements for metallic crowns or porcelain-fused-to-metal restorations. My recommendation for these types of restorations would be to use a glass ionomer or resin-modified ionomer cement.

Dr. Dalin: How about ceramic inlays, onlays, and crowns? Is there a difference in recommendations between fired porcelain, milled CAD/CAM ceramics, and zirconium materials?

Dr. Lowe: Ceramic restorations are quite different. A variety of cements can be used depending on whether or not the specific ceramic material is etchable. Ceramic inlays, onlays, or crowns that are made from feldspathic or stacked porcelain materials must be placed using total etch, dentin adhesives, and resin cements. Pressed ceramics and CAD/CAM restorations have a higher tensile strength than feldspathic materials. For some clinicians, these types of restorations must be placed in the same fashion as stacked porcelain - bonded using total-etch technique. Self-etching resin cements are reported to be excellent choices to place these restorations without using total etch. If you are using self-etching resin cements, (or in reality, any cement) always make sure that the preparation design contains adequate retention and resistance form. Ceramic restorations that are built on zirconium can be cemented using traditional cements, resin cements, or self-etching resin cements. Since zirconium cannot be etched, there is no advantage or need to use a total-etch technique with these types of restorations. I commonly use self-etching cements, or resin-modified ionomer cements for zirconium restorations.

Dr. Dalin: While we are on the subject of porcelain, what ideas can you offer regarding the proper placement of porcelain veneers?

Dr. Lowe: Since they are made of feldspathic porcelain materials, porcelain veneers must be placed using a total-etch technique, dentin adhesive, and resin cement technology. In this instance, the decision is whether to use a light-cured resin cement or a dual-cured resin cement. Depending on the operator’s preference, there are good reasons to use both. Some clinicians prefer light-cured resins for placing porcelain veneers because of the reported color instability of dual-cured systems. In time, this results in lowering of the value of the restoration. Cement cleanup with light-cured systems is usually more tedious, and in some cases, may require rotary instrumentation if the excesses are great. Dual-cure systems are more easily cleaned up because of the gel set that takes place. This allows the operator to remove a vast majority of the resin cement excess while it is still in a pliable state. Proponents of the light-cured method will say that dual-cured cement can be removed from the margin if cleaned up during a gel set. My view on this debate is that, if the margin is closed - as it should be - then you should not be able to remove cement from under the margin. Resin cements are not a cure for poor fit! My preference is the dual-cure technique when placing porcelain veneers. I have placed thousands of restorations, and have not experienced a darkening or lowering of value in the restorations. Remember that the film is so thin that the color of the cement should be a nonfactor. Try placing some resin cement between two microscope slides and see how much color comes through. If the restoration fits well and the film thickness of the resin cement is 10 to 15 microns, then there should not be a problem with color instability.

Dr. Dalin: Do your recommendations change when it comes to cementing metal posts? How about ceramic or fiber posts? Do your recommendations change?

Dr. Lowe: I do not use many metal posts like I once did. But when placing a metal post and core, I still prefer a modified resin ionomer cement. Ceramic or fiber posts can be placed using total etch, dentin adhesives, and resin cement technology. Some clinicians are starting to use self-etching resin cements for post cementation, too. Remember that when cementing a ceramic or fiber post with a dual-cured resin cement, use a dual-cured component or self-cure activator with the bonding resin to ensure proper cure.

Dr. Dalin: Here is a simple, yet perplexing subject: temporary crowns. In this category, there are many choices - ZOE cements, non-eugenol cements, and resin-based temporary cements. What choices are available? Please give us your recommendations.

Dr. Lowe: I never recommend a ZOE temporary cement because it may mask symptoms in a tooth in which the health of the pulp is questionable. With a near pulp exposure, or “hot” tooth, I think it is more important to clean and disinfect the surface of the tooth and make sure the provisional seals the margins well. Anti-inflammatory medications can be used to handle the subjective symptoms of the patient.

Cements containing eugenol can interfere with bonding if any residue remains on the preparation after removal of the provisional restoration. Non-eugenol cements are preferred for provisional restorations because of this characteristic. Resin-based provisional cements are worth considering, particularly for provisional veneer restorations. I prefer to lute provisional veneers using a spot-etch technique with flowable resin as the luting agent.

The majority of the full-coverage provisionals in my practice are cemented with polycarboxylate cement. Some clinicians mix it in water or Vaseline to make the polycarboxylate cement less retentive, but I usually use it “straight up.” These provisionals are well-retained and can be removed with a curved hemostat. The polycarboxylate cement that remains on the preparation is easily removed with a sonic scaler.

Dr. Dalin: I knew you would be the perfect person to help dentists get their thoughts organized about the multitude of choices we have today when it comes to placing restorations. We must be aware of the types of cements, and we must learn what works best with which materials. Then we need to see what works best in our own hands. When shopping for these materials, what questions should we ask of manufacturers’ representatives? On a related subject, do you enjoy hands-on training?

Dr. Lowe: There are many choices and outstanding products available to dentists in the cements category. When it comes to conventional cements, such as glass ionomers and resin ionomers, my main consideration is solubility (or lack thereof) of these products. Another factor to think about is dispensing and mixing. How is the cement packaged? How is it dispensed? Does it require a mixing device, such as a triturator? As far as hands-on training is concerned, there is no better way to evaluate a material than to try it. Ease of dispensing, mixing, consistency, and set times are all factors to consider when choosing the correct cement for you.Dr. Robert A. Lowe, DDS, FAGD, FICD, graduated magna cum laude from Loyola University School of Dentistry in 1982. He lectures internationally on restorative and esthetic dentistry, and has published numerous articles in dental journals on these topics. He has also been involved as a clinical evaluator of materials and products with many prominent dental manufacturers. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Jeffrey B. Dalin, DDS, FACD, FAGD, FICD, practices general dentistry in St. Louis. He also is the editor of St. Louis Dentistry magazine, and spokesman and critical-issue-response-team chairman for the Greater St. Louis Dental Society. He is one of the co-founders of the Give Kids A Smile Program. Contact him by e-mail at [email protected], by phone at (314) 567-5612, or by fax at (314) 567-9047.