Dentures: The Ugly Duckling

by Ian Shuman, DDS

Creating a denture is nothing short of a highly profitable, full reconstruction case. New materials have turned the ugly duckling of dentistry into a beautiful swan!

Can you put a value on the replacement of a missing eye with a prosthetic? You bet you can! I searched the Internet and located a variety of ocularist Web sites. For this highly valuable service, fees range from an average of $3,000 to $5,000 per eye. How about the value of a missing ear, nose, or limb? Like an eye, it's probably safe to assume that the majority of people would have these replaced immediately.

Now we come to the value of replacing an entire mouth of missing teeth. What if Mr. or Mrs. Edentulous discovered that this tremendously valuable service would increase the height of shrunken jaws, eliminate wrinkles, improve chewing and digestion, and help them avoid the disastrous consequences of TMD?

Over 60 million people are edentulous in the United States alone, many of whom are not denture-wearers. Nondenture-wearers are a tough crowd. Often, they are "doing just fine thank you" without teeth. Oddly enough, among the minority of the denture-wearing set, most have adapted to their ill-fitting, 20-plus-year old dentures, or they are quietly unhappy, only wearing their dentures for the occasional night-on-the-town.

Old and new denture realities

"Many dentists refuse to take full-denture cases because of the poor end results. Poor end results invariably make a dental practice unpleasant and unprofitable. The conscientious dentist hesitates to charge a fee for services that he feels will fall far short of the patient's expectations. Therefore, many dentists consider the denture patient an economic liability."

The above quote — which certainly reflects current sentiment — was eloquently stated by Ewell Neil, DDS, in 1941, at a time when dental schools required numerous units of complete denture fabrication to graduate, and state dental boards required a demonstration of complete denture fabrication on a live patient. Today, many dental schools have virtually eliminated complete denture fabrication from their curriculum; most state boards no longer require proficiency in complete dentures to receive a license. The perception among today's dentists is that the complete denture is difficult to create and the fully edentulous patient is even more difficult to treat. It then becomes simple to realize why dentures are the ugly duckling of the dental world: They are misunderstood and poorly made.

Why do we hate dentures?

We can all remember painful dental school memories, and we frequently use these as excuses for not performing one dental service or another. However, as Dr. Ewell stated, the two most common reasons for dentists not performing this valuable and lucrative service are an unpredictable outcome and an economically unprofitable result.

The problem with any outcome is lack of education and careful planning. As mentioned, today's dental schools only require a few denture units to be made for graduation, and many State Boards no longer have a denture section on the clinical portion of their licensing exam. Because of this, dentures end up last on a recent grad's list of "to do's" in patient care. Frequently, this attitude continues throughout the dentist's career.

To worsen matters, the perception is that dentures just aren't very profitable. They are viewed as a financial vacuum because the doctor undercharges for a service deemed "meritless." So, the patient underpays when the service is performed and the sense of value is lost. Understanding these two factors is critical if we are to appreciate and correct the problem.

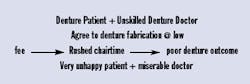

If we were to create a flowchart for the doomed denture, here's what it would look like:

The thought-changing process

What turned around the financial wasteland and time vacuum of denture care in my own mind was a conversation I had several years ago at the Profitable Dentist annual seminar. It was held in March in Destin, Fla. The beach was pure white, and the sun and breeze made relaxing easy. I was enjoying a beach-side lunch break with Dr. Charles Barotz, a highly successful colleague from Denver, Colo. He was explaining his philosophy of denture care.

In his opinion, creating a denture is nothing short of a full reconstruction case and should be treated as such. They are fun, highly predictable, and outrageously profitable. Dentures are full reconstruction, occlusal splints, and TMJ protective devices. They also are "instant orthodontics." Dentures are the gateway to proper digestion and nutrition, allowing their owners to be easily understood when speaking because they now have proper phonetics. Then Dr. Barotz asked me a question: "If payment were equal, would you rather make impressions and take wax records for a denture or prepare a full arch of teeth for crown and bridge?" The ultimate outcomes are very similar, with the most significant difference being that one is fixed with a metal base (cores), while the other is removable with an acrylic base.

His philosophy included scheduling adequate amounts of time and charging an appropriate fee for that time. As we all know, a single, full-reconstruction case can rival the cost of a new car. And although dentures would not be priced that high, they should be priced at an amount that reflects the time, care, and dedication put into each case.

At that moment the "aha lightbulb" flashed. Upon my return home to Baltimore, I was determined to change my fees and my approach to this service. Gone were the days of the "$800-per-unit insurance-dreamt-up-UCR-because-I-had-no-idea-what-to-charge-in the-first-place denture!"

Adding credibility to these ideas, Dr. Roger Levin created a workbook for dentistry called Dentures: The Hidden Growth Center in Dentistry. In his opinion, "U it is vital to remember that traditional services still account for the majority of revenue in most dental practices U and often present the greatest opportunity for revenue growth. Along these lines, we shouldn't ignore one of the most readily available practice-building services that is already sitting there in our files — the denture!

The need for denture services is as great as it has ever been in the United States. It is one of the most profitable services that can be offered with reasonably predictable quality. And, in most general practices, dentures can add significant levels of productivity when addressed and promoted properly."

The next step: education and economics

Once you decide to embark on the path of the few, learning how to make a great denture is the first step. The most critical part of this is a good first impression. The finest impression system I have found is the Accudent System 1 Impression System (Ivoclar North America, Inc). This irreversible hydrocolloid material is used as a wash/base with specially-designed edentulous trays. I find that these make excellent primary impressions and I use them to create my study models. We pour these using white Fujirock (GC America) which creates a gorgeous, smooth model that both impresses the patient in the case presentation, and serves as an excellent base for custom-tray fabrication. Another option is to use a quick-setting stone like Snapstone (Whip Mix Corp.). Within five minutes, a working model can be created, ready for custom tray fabrication.

Custom trays were never my favorite activity. In dental school, the sprinkle-powder, polymer/liquid monomer technique was truly an awful experience that probably made permanent changes to my DNA. This led to my searching for shortcuts, all of which never led to a truly satisfactory result. However, along came Triad Transheets (Dentsply), colorless light-cured sheets that are formed into custom trays. Using the traditional wax layer, three vertical stops, and Triad, the finest custom trays can be made easily, rapidly, and immediately. Following border molding the old-fashioned way with Kerr Type I greenstick-impression compound over a Bunsen burner, a final impression is made using what I consider the finest final-impression material available: Honigum (Zenith DMG). Using a very nontraditional technique, we create a polyvinyl base/wash impression in two steps using Honigum Mixstar heavy body wash followed by Honigum Automix light body wash.

These final impressions are then poured using Silky Rock (Whip Mix Corp.), an extremely low expansion dye stone. I feel that with all of the abuse the final model takes (such as constant record-base removal and waxing), it should be able to stand up to it. The expense of these steps is higher than traditional materials that we were taught to use. However, the final outcome of a well-fitting denture far outweighs the cost of a patient returning multiple times for adjustments. Record bases are made in-office with Triad Regular Pink Unfibered sheets and pink base-plate wax. Records are recorded and the casts are mounted on a Protar 5 semi-adjustable articulator (Kavo). For denture teeth, I only select the best, and for my patients, the best are the Trubyte Portrait IPN anterior teeth and Trubyte IPN 10∞ Anatoline Posterior teeth (Dentsply). Because we are creating both function and beauty, these teeth truly allow for excellence in both. In addition, posterior 10∞ teeth are ideal in order to allow for the most gentle excursions, while offering the patient some degree of inclination to perform proper mastication. Once tried in at the wax stage, the patient has the opportunity to make any final comments, criticisms, or praise, and the denture can be completed

The above highly-abbreviated version of denture fabrication is an overall view of the forest. For a real glimpse of the trees, it takes a few hands-on courses, a handsome collection of home videos and DVDs, and lots of practice to get you on your clinical way.

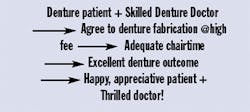

If we were to look at a flow chart for the dream denture, it would look like this:

null

Creating a business model

You'll need to create a business model to enjoy creating excellent dentures while providing patients with the dentures of their dreams. Use the following guide as your model:

Your time, in terms of dollars, should include:

- Office overhead calculated on an hourly basis.

- Your increased skill with time. Make sure to "amortize" the dollars spent on continuing education.

- The pain factor: The more difficult the patient, the higher the fee. (If they balk, you won't miss them. If they stay, you will be handsomely paid for your trouble.)

- Lab fees.

- Materials.

- Profit. (This is defined as any additional money you want to make over and above all of the factors included above.)