CBCT and implants: Improving patient care, one implant at a time, Part I

By Edward J. Mills, DDS

For more on this topic, go to www.dentaleconomics.com and search using the following key words: CBCT, implant dentistry, 3-D dentistry, bone density, Edward J. Mills, DDS.

Without question, the initial perceived value of computer-assisted, 3-D analysis of dental patients was associated with treatment planning and the delivery of dental implants. As the technology became widely used by dentists, its application was dramatically enhanced. A clinician's ability to view images in three dimensions, as well as share clinical findings digitally, enhances the scope of the patient exam.

Using dental cone beam technology for the differential diagnosis of lesions, to determine the relative location of teeth or roots to critical anatomical features, and for assessments of endodontic pathology - all in 3-D - are just a few examples of the numerous ways in which the technology has greatly enhanced patient care.

Incidental findings in cone beam studies are often discovered when digital data is shared with an oral and maxillofacial radiologist. Cranioskeletal, neurologic, ENT, and even vascular pathology or other abnormalities can be identified using cone beam technology.

The dentist then becomes a critical source of referrals to a wide spectrum of clinicians. This network of clinicians results in improved comprehensive care of patients and the development of individual practices.

In addition, the technology has the ability to detect subtle variations in bone density, which can help predict future patient conditions and help determine the predictability of surgical procedures and the longevity of restorative treatment.

What's more, quantifying relative bone density around dental implant abutments and natural teeth can help with the assessment of periodontal or peri-implant status much sooner than with traditional clinical techniques. Early conservative treatment, such as altering occlusion, can improve the prognosis of a patient's dentition or restorations.

Growing demand for implants

Dental implantology was pioneered in the 19th century. Since the American Dental Association (ADA) endorsed the practice in 1986, the market for implant dentistry has grown rapidly and been aided by technological advances. Beyond replacing teeth lost to injury, increased life expectancy and esthetic concerns accelerate the wide acceptance of implantology. Implants improve quality of life for patients who are able to keep their natural teeth, fix acute problems, and give patients the benefit of restorative improvements for a modern lifestyle.

Another factor in dental implant growth is increased life expectancy. Life expectancy averages more than 66 years worldwide, and the 2009 CIA Factbook places the average American's lifespan at 78 years, and 80 years for Europeans.

As these populations age, prevalence and incidence of age-related dental complications are expected to increase accordingly. Tooth loss due to age – because our lives have extended beyond the timeframe for which our teeth were designed – has contributed to increased demand for dental implants.

Also driving the growth in implants, particularly in the U.S., is a rise in complex and esthetic dental work with the aging of the baby boomers. As this significant and affluent demographic hits middle age, many choose implants in lieu of bridges or dentures.

But it is not just baby boomers making this choice for esthetic reasons. The general cosmetic surgery market is growing as more youthful Americans undergo facelifts and other cosmetic procedures. For many, a perfect smile is a key component of a makeover.

The dental implant market also benefits from the success of implants, particularly when compared to root canals. Data show that a growing number of root canal candidates would rather take the tooth out and get an implant.

An ADA survey found that the average number of implants placed by dentists was 56 per year in 1999, compared with 18 in 1986. More recently, the American Academy of Implant Dentistry shows that U.S. dentists performed 5.5 million implants in 2006. According to Millennium Research Group, South Korea, and many European countries are outpacing the U.S., with data showing dental specialists perform up to three times as many implants annually in these countries.

3-D technology: the new paradigm for implantology

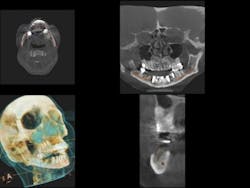

As practitioners work to meet the growing demand for implants, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is an essential tool for treatment planning and post-procedure monitoring. By providing highly accurate 3-D images of the patient's anatomy from a single, low-radiation scan, CBCT technology delivers a comprehensive understanding of the patient's jaw and the anatomical structures necessary to properly provide treatment (Berger et al.). (See Fig. 1)

To ensure a successful implant placement, one must take into account the patient's prosthetic needs, functional requirements, and anatomical constraints. During the assessments, 3-D imaging contributes to a greater success rate due to its ability to visualize previously undetectable anatomic variability and pathology.

Simply put, CBCT-generated images provide detailed information that 2-D radiographs cannot offer. This greatly aids in precision, which improves the entire implant process.

There have recently been concerns regarding the amount of radiation dosage in medical CT scans. Unfortunately, these reports have created misunderstandings regarding dental scans, specifically CBCT scans. While radiographs are one of the best diagnostic tools available to medical and dental practitioners, radiation safety has become a critical issue.

Repeated patient exposure to radiation over long periods of time is associated with irreversible eye damage, genetic defects, and the development of malignancies in the lens of the eye, thyroid, salivary glands, bone marrow, and skin.

As a result, it is essential that health-care professionals be especially careful and thorough when radiation is used to ensure minimal exposure to patients. Ionizing radiation should be used only when and where it is indicated.

Patients should always be informed of the potential risks, benefits, and alternatives. Practitioners also should subscribe to the ALARA Principle, "As Low as Reasonably Achievable," which dictates that every precaution should be taken to minimize radiation exposure to patients.

Without the aid of 3-D imaging, doctors often must speculate on bone density or exactly how deep implants need to be. Panoramic radiography, conventional CT scans, and CBCT scans provide information about each implant site. CBCT images, with less distortion than 2-D images, are more accurate in showing bone height and width and allowing for accurate measurements of jawbone thickness, while defining the shape of the bone contours.

One CBCT scan can include the entire maxillofacial region, including the maxilla, mandible, base of skull, and temporomandibular joints. As a result, CBCT allows oral surgeons to accurately locate the position of the inferior alveolar canal in the lower jaw, thus minimizing the risk of nerve damage (Cevidanes et al.). In the upper jaw, use of 3-D imaging during the implant planning process or surgical phase can aid inserting implants around the maxillary sinus, or assist in surgery where the maxillary sinus is augmented with bone.

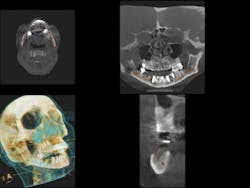

The anatomy and health of the maxillary sinus are critically important during augmentation or subantral augmentation of this area. The more information a clinician has before addressing this region, the more predictable the results. (See Figs. 2a and 2b)

The advantages of CBCT technology over panoramic radiography and conventional CT scans don't end with enhanced imaging of implant sites. While pan tomography is still widely used and provides a convenient and inexpensive method with low radiation exposure, it has several limitations. CT technology has several restrictions, too, including device costs, radiation exposure, and operational availability.

A CBCT scanner renders high-resolution images for one-tenth the cost and a fraction of the radiation compared to a CT scanner. CBCT technology also allows dentists to avoid restricted visualization and errors, including nonuniform magnification, diagnostic restrictions in the anterior areas, missing cross-sectional information, superimpositions, cephalometric orientation, and problems of geometric distortion. In these areas, CBCT has become the leading method for evaluating dentofacial structures related to implant planning because it ensures safe and accurate implant positioning (Cevidanes et al.).

Comparative diagnostic applications of CBCT versus other tools

Prior to implantation, an investigation of the planned implant site is required to visualize the available bone and surrounding anatomical structures and augmented areas that could be affected. For this process, CBCT data is critically important in planning for the insertion of not only single implants, but also in the surgical treatment planning for multiple implants (Dreiseidler et al.).

A single scan generally provides accurate diagnostic information. Fewer scans mean less exposure: radiation exposure from CBCT is up to 10 times less than that produced by expensive medical CT scanning. Unlike 2-D radiographs, CBCT scans differentiate between bone, teeth, nerves, and soft tissue.

A CBCT scan provides precise information about pathology, the locations and dimensions of vital anatomical structures, bone quality, and any issues that might interfere with treatment planning. The Kodak 9000 3-D extraoral imaging system allows for a broad overview of the patient's dentition with one of the most accurate panoramic images available.

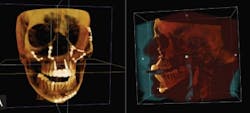

It also allows for the 3-D evaluation of an arch, either in sections or an extended field of view (FOV) option, allowing the full arch to be viewed as a whole three dimensionally. This view helps practitioners correctly identify the region of interest the first time, which results in lower cost to patients because less time and money is consumed for repeated office visits. (See Fig. 3)

When detecting pathology, 3-D imaging makes it easier to develop a treatment plan. The Kodak 9500 cone beam 3-D system provides a larger FOV, which allows for treatment planning of complex implant cases involving both arches. A large FOV also provides incidental findings that may prove valuable in a patient's overall assessment. While locating vital anatomical structures - for example, the maxillary sinus, temporomandibular joints, and the mandibular nerve canal - any abnormalities found can impact implant planning (Hatcher). Common incidental findings include plaque, carotid arteries, sinus pathology, craniofacial lesions, and more.

The larger image may also provide information about dental pathology that may not be the patient's chief concern. These findings may include the nature of endodontic failure, relative position of impacted teeth, or other details essential to developing a treatment plan.

Information about the axis orientation of the alveolar bone, in particular, is essential for successful alignment of the implant within the boundaries of the jaws. With this, the doctor may optimize the trajectory, emergence profile, and loading characteristics of the implant.

Bone density is directly proportional to its load-bearing capacity – implant failure is often associated with low bone density or osteonecrosis, which can occur spontaneously or after invasive dental procedures. (See Fig. 4)

Countless clinicians have successfully placed implants using only 2-D imaging. As a result of significant information received from 3-D studies, however, practitioners can decrease potential risks and dramatically enhance predictability in results due to thorough analysis and preplanning.

For example, my staff has not placed an implant in our practice for more than 10 years without a CT assessment before surgery. The accurate relative positioning of implant fixtures is critical not only to avoid anatomical landmarks, which can result in injury to the patient, but also for obtaining optimum esthetic results and longevity of the implant fixture and prosthesis.

Next in the series: Dr. Mills details why CBCT is an essential treatment tool, explains what oral health professionals might expect as a return on investment in CBCT technology, and expands upon ways in which patients benefit from this new standard of care.

References available upon request.

Edward Mills, DDS, is the founder of the Atlanta Center for Restorative Dentistry in Atlanta. A 1980 graduate of Emory University, he has lectured extensively throughout the world on state-of-the-art, restorative dental techniques. Dr. Mills is a fellow and past president of the American Academy of Implant Dentistry, as well as a diplomat at the Board of Oral Implantology.