A look at the new CDC guidelines

by Curt Hamann, M.D., Kim Sullivan, and Pamela A. Rodgers, Ph.D.

By now, many dentists have received the new 2003 infection control guidelines published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The current 68-page document may appear daunting by comparison to its 1993 predecessor. It includes an extensive background, discussion of supportive data, informative appendices and a summary of specific infection control recommendations. It revises and updates recommendations and requirements to be consistent with current information from the CDC, Occupational Safety and Health Adminstration (OSHA), and various dental professional organizations. Some dental workers may object to the perceived added burden or costs associated with implementation of these guidelines. But, for the most part, these updated recommendations admonish dental professionals to continue to adhere to the same infection control guidelines already established for dentistry and other health-care fields. Moreover, the revised recommendations can reduce the risk of increased insurance costs from unwarranted pathogen transmission. This article is designed to highlight the critical changes and their implementation in your dental practice.

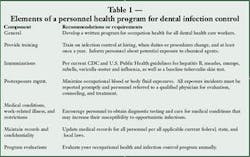

Health policies for all

Consistent with the 1993 guidelines and OSHA's standard precautions, the CDC recommends developing a comprehensive written occupational health program for dental workers, with extensive employee training (Table 1). In addition, staff occupational health documentation must be maintained in a confidential, secure manner consistent with all local, state, and federal regulations. Recommended program components include employer-provided immunizations, baseline tuberculin skin tests, exposure prevention, work restriction policies, and arrangements for potential postexposure prophylaxis. While most are already mandated by OSHA, implementing some program components may require additional costs.

New to the 2003 guidelines are recommendations that dental practices establish written work restriction policies for dental professionals infected with or exposed to major infectious diseases. These must include a written statement, as well as training, to identify who is responsible for excluding dental personnel from work. These recommendations are intended to unify work practices and infection control policies for all health care workers. The additional time off work included in these recommendations may appear unwarranted until the potential costs of disease transmission are considered. For example, many office staff dread the annual onslaught of winter respiratory viruses or episodes of conjunctivitis, knowing that they can easily migrate to personnel, family members, and patients.

Per the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act of 2001, dental practices are also required to take steps to prevent occupational blood exposures. Common sense dictates preserving safe-work practices for sharp instruments and needles. The CDC also recommends the annual evaluation of engineered safety devices such as dental safety syringes, which can be easily accomplished using forms available from both the CDC and OSHA websites. This evaluation process also provides information and feedback to the industry to help engineer better devices for sharps injury protection.

Most of these requirements are not new to dentistry or health care. Education and training are priceless in preventing occupational injury and disease. Studies conducted by the American Dental Association in the 1990s suggested that over 90 percent of dentists had received hepatitis B vaccinations. Compliance appears similar for dental hygienists and assistants (personal communication, Chet Siew, Ph.D., ADA). The increased immunization levels no doubt reflect OSHA mandates, increased awareness, and school immunization requirements. Certainly, immunizations are cost-effective — hepatitis B vaccinations generally cost less than $300 for three doses and a titer measurement, whereas treatment costs for chronic hepatitis B begin at $3,000 and increase exponentially with the onset of cirrhosis and permanent liver damage.

If an exposure incident occurs, dental personnel are required to follow CDC and U.S. Public Health Service postexposure guidelines. These encompass immediate care to the exposure site and provision of appropriate postexposure prophylaxis. The latter must be provided by a qualified occupational health physician familiar with current postexposure recommendations for bloodborne pathogens. Due to the complexity of some postexposure regimens, and the importance of expedient treatment, the CDC now recommends that dental practices make advance arrangements for needed testing and treatment.

The costs of postexposure prophylaxis will vary. For hepatitis B, expenses include blood titer measurements and hepatitis B booster administration for approximately $100 to $200. However, HIV postexposure prophylaxis costs at least $500 for the minimum four week two-drug treatment. With medical follow-up, testing, and treatment, overall HIV prophylaxis costs can exceed $1,500 per exposure incident. Because exposed workers can still seroconvert after prophylaxis, sharps injury prevention and safety programs should not be underemphasized.

Dental practice managers may also be concerned about the time commitment (and related revenue costs) associated with implementation of the revised CDC infection control guidelines. A trained infection control coordinator can efficiently update existing or develop new office policies and educational programs, as well as communicate their value to patients. Professional organizations such as the ADA and OSAP can provide various resources to help dental practices improve their infection control programs. Implementation may require that staff take some time away from direct patient care. However, remember that infection control adds tremendously to the safety and quality of all patient services as well as employee health.

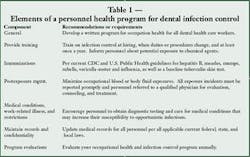

Using protective equipment

As in the 1993 guidelines and per standard precautions, the CDC requires the use of medical gloves, protective clothing, masks, and eye protection during patient care (Table 2). However, the current guidelines provide significant guidance on the selection and proper use of these items for dental patient care. New recommendations include the use of solid side shields for protective eyewear, thick utility gloves for instrument cleaning and housekeeping, and sterile surgeon's gloves for oral surgery. Of these, the latter is potentially the most controversial and costly. The 2003 guidelines specifically recommend using sterile surgeon's gloves for procedures that "involve the incision, excision, or reflection of tissue that exposes the normally sterile areas of the oral cavity." While already standard practice for many oral surgeons, other practitioners may not commonly use sterile surgical gloves due to their 10- to 20-fold greater cost.

Current 2003 guidelines also include greater detail about specialized equipment needed in managing dental patients infected with tuberculosis. Dental practices that regularly treat these patients must develop a written tuberculosis control program that includes respirator protection, as well as proper ventilation and engineering controls. Disposable N95 masks — not surgical masks — should be worn when treating these patients. Approximately six times more expensive than surgical masks, the use of N95 masks also requires fit-testing, additional training, and documentation. Due to these additional costs, facilities, and program requirements, these patients are best treated at institutions already equipped with tuberculosis engineering controls and a respiratory program.

Take care of those hands

As dental professionals are aware, hand hygiene is the most important means of reducing potential pathogen transmission during patient care. Unfortunately, more than one-quarter of dental and medical personnel reportedly do not wash their hands after caring for patients. These and other poor hand hygiene habits can contribute to skin infections, dermatitis, and disease outbreaks. To improve hand hygiene compliance, these new CDC guidelines provide guidance on the appropriate use of plain soaps, antimicrobial soaps, and alcohol-based hand rubs, as well as antimicrobial soaps and alcohol rubs with persistent activity for oral surgical antisepsis.

The use of alcohol-based rubs is new to dentistry, but has been shown to be useful in hospital environments. These products can reduce bacterial contamination in a cost-effective manner and improve hand hygiene compliance. Using alcohol rubs that contain emollients or humectants may improve the dry or irritated skin associated with poor hand hygiene practices. However, not all emollients and humectants are equally effective. More importantly, using alcohol rubs cannot replace hand washing. Hospital studies have found that hands must still be washed at least once for every five to 10 applications of alcohol rub to prevent the buildup of hand rub additives and to keep hands clean.

The new CDC guidelines also encourage hand lotion use to prevent and ease skin dryness. However, caution is warranted when using any lotion under gloves. Mineral oil and petrolatum additives in lotions and creams can damage or weaken natural rubber latex gloves. In addition, some lotions can increase exposure of skin to potential allergens, worsening a skin condition.

The hand hygiene recommendations encourage workers to maintain skin integrity, a core principle in preventing disease transmission. Healthy skin is a vital barrier against damage from abrasion, chemical irritants, and infectious agents. Therefore, it's not surprising that the CDC guidelines advise dental professionals to educate themselves about irritant and allergic contact dermatitis, as well as latex (type I) hypersensitivity. The guidelines also make recommendations about caring for patients with latex (type I) hypersensitivity, including establishing a "latex-safe" environment and isolation from products that contain natural rubber latex. These solid recommendations are derived from latex-allergic patient management protocols from the American Dental association, National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety and numerous health care organizations.

The CDC guidelines suggest that dental professionals maintain short nails in good condition, and advise against the use of artificial fingernails and finger jewelry. Both artificial fingernails and jewelry can provide a safe haven for the growth of transient microorganisms that are frequently the source of disease transmission. In addition, these personal fashion statements facilitate premature glove failure and can increase glove costs. Artificial fingernails create another unique problem for dental professionals: both nail glue and dental bonding agents can contain allergenic methacrylates. As a result, dental professionals frequently develop contact allergies to methacrylates. The symptomatic broken skin and red, edematous sores grossly undermine hand hygiene and infection control practices.

These recommendations on hand hygiene should have little impact on current practice supply expenditures. Theoretically, these recommendations could, when properly implemented, lower practice management costs by reducing time away from work due to occupational skin disease. As indicated by the recent report of hepatitis C and HIV transmission to a health care worker with broken skin, the value of appropriate hand hygiene should not be underestimated.

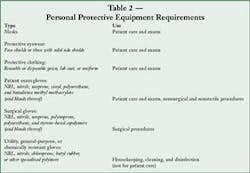

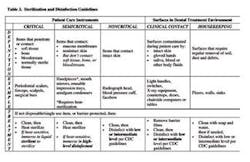

Clean and decontaminate wisely

The 2003 recommendations for sterilization and disinfection procedures include far greater detail than the 1993 guidelines, but are unlikely to markedly increase general practice costs. Sterilizer monitoring recommendations are also more specific, but reflect common sense from both infection control and engineering perspectives. For example, practices handling dental implants should now include both biological and chemical indicators in each load, and verify spore test results before implant use. Storage recommendations have also increased, which may motivate facilities to allocate more space to packaged sterile equipment and supplies.

Due to the differences in label claims, choosing an appropriate disinfectant can be confusing for dental practices. The 2003 CDC guidelines offer considerable background information, including discussion of disinfectant nomenclature, specified uses, and regulations. Moreover, recent regulatory changes (CDC, FDA, and EPA) should eventually create greater consistency for consumers in product labeling. The use of the terms "hospital grade" or "hospital strength" for disinfectants should disappear, and dental practitioners should be able to identify potency by category. Briefly, three categories exist — low-level disinfectants with hepatitis and HIV claims, intermediate level disinfectants with a tuberculocidal claim, and high-level disinfectants and sterilants (Table 3). As before, the CDC guidelines emphasize that these chemicals should only be used according to manufacturer instructions. Moreover, because the risk of disease transmission from dental workplace surfaces is minimal, the CDC recommends general housekeeping with simple detergent and water. Common sense indicates that higher levels of disinfection should be reserved for treatment of equipment and surfaces that are potentially contaminated with body fluids. These recommendations should improve the ability of practitioners to select cost-effective disinfectants and sterilants, and apply them in a practical manner.

Infection control measures for dental waterlines have also been expanded from the original 1993 guidelines. Water quality must meet EPA drinking water standards, including specified acceptable levels of bacterial contamination. In addition, antiretraction mechanisms, handpieces, ultrasonic devices and air/water syringes in dental units must be regularly maintained per manufacturer instructions. These recommendations reflect good infection control policy, cost little, and can add practice value — especially when communicated to patients.

Dental labs and radiology

New to the 2003 guidelines, the dental radiology recommendations emphasize procedures that minimize pathogen transfer via radiological devices. The CDC admonishes the use of heat-tolerant or disposable intraoral devices rather than those that require liquid disinfection or sterilization. For digital radiography equipment that is not disposable or heat-treatable, the use of FDA-cleared barrier materials with intermediate level disinfection is advised. As in other areas of dentistry, gloves and aseptic procedures should be used when handling and transporting radiographs and film.

More specifics have also been added to the 2003 guidelines regarding cleaning and disinfection of prostheses, prosthodontic materials and dental laboratory tools. As in other areas of dentistry, the use of personal protective equipment is advised in the dental laboratory. Intermediate-level disinfectants with a tuberculocidal claim are again recommended for disinfecting these patient items. Guidance should be sought from manufacturers regarding the compatibility of prosthodontic materials and tools with the disinfection procedures selected. New to the 2003 guidelines is the recommendation that dental practices and laboratories identify the disinfection process used on transferred patient items. This can be easily accomplished through the use of appropriate labeling procedures, without significant cost. These new recommendations should solidify current infection control practices for most dental offices and laboratories, without substantial increases in costs.

Other new issues

Included in the 2003 guidelines are new specifics on aseptic procedures for the administration of parenteral medications. The CDC recently reported several cases where patient-to-patient transfer of hepatitis B and C occurred due to improper aseptic technique during medicament administration. These new guidelines admonish dental professionals to use single-dose vials whenever possible. As recommended generally in health care practice, when multiple-dose vials are used, they must only be accessed by single-use sterile syringes and needles. Adhering to these guidelines may slightly increase supply costs, but will prevent possible transmission of bloodborne pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis.

Final words

The new 2003 infection control guidelines published by the CDC emphasize better patient care and improved health for dental workers through solid infection control practices. The revisions update and expand its decade-old predecessor. In the spirit of unifying disease prevention throughout healthcare, it incorporates pertinent recommendations from other fields of health care, as well as applicable regulatory changes. Moreover, the extensive review of background information provided is a valuable resource for dental practitioners.

Fortunately, few of the recommended changes in dental infection control practices involve significant expense for the dental practitioner. The use of surgical gloves and sterile irrigants during oral surgery, and the time required to implement administrative changes are probably the most costly. Regardless, these changes in dental infection control can reduce the risk of disease transmission between patients and dental care staff. Even the most penurious practitioner can afford to invest in these value-driven expenses.

Editor's Note: References available upon request.