Ask Dr. Christensen: What are the best techniques for electric dental handpieces?

Despite electric dental handpieces being available for several decades, less than half of US dentists use them in their practices. Dr. Gordon Christensen discusses advantages and limitations of low- and high-speed electric handpieces, and recommends that dentists who are not currently using them consider augmenting or replacing their air-driven handpieces with electric.

Q:

MY LOCAL DENTAL DISTRIBUTOR, who frequently visits my office, has been educating me on electric dental handpieces. I have never had the opportunity to use electric handpieces other than on a trial basis, but it appears that I am missing some of their important advantages. Would you agree that the advantages of electric handpieces are worth their considerable cost? Where should they be used?

A:

In spite of electric handpieces being available to the dental profession for several decades, most dentists in the United States still use air-driven handpieces most of time. That is not the case in the majority of other developed countries. In my opinion, one of the reasons why most US dentists have stayed with air handpieces instead of moving to electric ones is because the concept of air-driven handpieces was invented and introduced here in the late 1950s; dentists are relatively satisfied with them. Air-driven handpieces are adequate for most procedures, but some dentists have not had the opportunity to experience the advantages of electric handpieces.

There are some procedures for which electric handpieces are more advantageous than air. Why is this? The major advantages are that electric handpieces have significantly more torque (power) than air handpieces, and that torque is constant. When cutting with an air handpiece, the rpm reduces significantly. When cutting with an electric handpiece, the rpm remains constant even when cutting at a maximum of about 200,000 rpm with very little reduction in torque. The bur rotation is concentric, assuming the handpiece has been well-maintained. The electric handpiece runs smoothly without noticeable vibration, and the rotation can be reversed when desired.

Are these advantages important?

Low-speed electric handpieces

Here are a few of the low-speed procedures that are best accomplished with electric handpieces.

Cutting resin: If you are remodeling a resin occlusal splint or denture base that the laboratory made too thick, low-speed air handpieces will often stall out during removal of a significant amount of resin. It is frustrating to have to take time to remove the excess bulk of resin. Low-speed electric handpieces have so much torque that you must hold the appliance you are trimming very tightly, or the handpiece will rotate it out of your grip. The reduction in time to do the resin-trimming procedure and the ease with which the electric handpiece cuts are immediately observable.

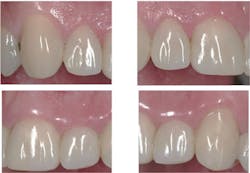

Finishing procedures: When finishing a composite, you have undoubtedly had the experience of making a “white line” on the margin of the restoration, especially on Class I and Class II restorations. What is the white line? We have looked at such clinical situations microscopically and found that the line is fractured tooth structure and fractured composite, which creates a microscopic trench along the restoration margin. When an air-driven handpiece is used to finish composite margins, one must run it at relatively high rpm, or it will stall out and quit cutting. Low-speed electric handpieces can be run at a very low rpm and still have torque enough to gently shave away excess resin without abusing it or the tooth structure margin. If accomplished carefully, you will immediately notice fewer white lines (figures 1–3). When disking any restoration with a low-speed air handpiece, the same challenge occurs. Disking should be done at low rpm, and it is often necessary to run the disk in the reverse direction. Air handpieces stall at low speed, while electrics can be run at a few hundred rpm to finish restorations easily and without abuse, and the rotation can be reversed.

Prophylaxis procedures: The same phenomenon is present when doing prophy polishing at low speed. Electric handpieces have enough torque at low speed to adapt a rubber cup or finishing and polishing rotary instrument easily to the tooth contour without stalling, thus reducing heat and allowing more control (figures 4 and 5).

High-speed electric handpieces

How do high-speed electric handpieces compare to high-speed air handpieces? As you know, preparing teeth for crowns requires significant time and effort. When you are trying to be time-efficient in such cases, air handpieces often stall out. This does not happen with electric high-speed handpieces; they cut with ease and high torque. There is a well-known negative to the above statement, however. If you happen to slip and the cutting instrument engages soft tissue, the extra torque of the electric handpiece makes the handpiece keep going longer. This can potentially cause more damage to the soft tissue than air handpieces, which stall and stop rapidly.

Reducing bur damage to soft tissue: I have a technique to reduce the chance of soft-tissue damage. Use a high-speed air handpiece for the initial preparation of a significant number of teeth for crowns. Gross preparations can be accomplished down to the gingival line. When this is done rapidly, you can then switch to an electric handpiece at much lower speed and higher torque to finish the preparations. This will reduce inadvertent bur damage to soft tissue.

Concentricity: Most electric handpiece users agree that the degree of precision offered by electric high-speed handpieces allows you to make more refined tooth preparations.

Cutting off crowns: Removing defective crowns and fixed prostheses is greatly facilitated by electric high-speed handpieces, because of their high torque and ability to use more aggressive cutting force. In spite of more aggressive cutting, the sound electric handpieces produce is significantly less than the noise generated by air handpieces.

What are the limitations of electric handpieces?

One of the reasons dentists have been slow to switch to electric handpieces is the cost of purchasing them and setting them up in the dental office. In spite of the higher cost, however, I predict that anyone who purchases these handpieces will recognize their value as soon as they begin using them.

In our evaluations of high-speed electric handpieces, we observed that some brands have a larger handpiece head. Some are also heavier than typical high-speed air handpieces. Although some dentists claim more maintenance is necessary for electric handpieces, that complaint is directly related to how well they clean and lubricate them.

As with any new concept, there is a short learning curve to adapt from air handpieces to electric handpieces.

What attachments are necessary for electric handpieces?

Most dentists who have electric handpieces use three attachments with them:

- A 5:1 high-speed attachment (runs from about 5,000 rpm to about 200,000 rpm) is used for routine tooth preparations in place of a typical air turbine handpiece.

- A 1:1 slow-speed contra-angle attachment (runs from very low speed to about 40,000 rpm) is used for finishing restorations with carbides or diamond rotary instruments, disking, post channels, pin placement, and other slow-speed tasks that require a latch-type shank.

- A 1:1 straight attachment is used for adjusting dentures, orthodontic appliances, provisional restorations, and other similar tasks. As with the contra-angle above, the rpm ranges from very slow to 40,000. The torque for the straight attachment is astounding and highly appreciated when removing a significant amount of material.

Summary

Low- and high-speed air-driven handpieces have served the dental profession very well. However, high- and low-speed electric handpieces, used by less than 50% of US dentists, can augment or replace air-driven handpieces. Many dentists use both types of handpieces in clinical situations most appropriate for either type’s specific advantages. It is suggested that dentists who are not currently using electric handpieces carefully evaluate the advantages of incorporating them into their practices.

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD, is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah. He is the founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing-education organization initiated in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is cofounder (with his wife, Dr. Rella Christensen) and CEO of Clinicians Report (formerly Clinical Research Associates).

About the Author

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD, is founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses and cofounder of Clinicians Report. His wife, Rella Christensen, PhD, is the cofounder. PCC is an international dental continuing education organization founded in 1981. Dr. Christensen is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah.