Single-use of dental burs and diamonds: Results of a survey among Dental Economics readers

Editor's note: An abridged version of this article may be found in the January 2021 issue of Dental Economics.

Introduction

Dental carbide burs and diamonds are essential to the practice of dentistry and the dental bur block is a ubiquitous sight on the assistant carts or bracket tables in most dental offices. Traditionally, burs and diamonds have been viewed as a reusable resource that could be cleaned, packaged, sterilized, and discarded when they break and can no longer cut efficiently. Dental health care personnel (DHCP) must also make decisions on how to safely and effectively clean and reprocess rotary and manual endodontic files, mandrels, finishing wheels and points, surgical burs, and specialized burs such as those used for implantology.

The Recommendations for Infection Control in Dental Settings published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2003 (updated 2016) recommends that burs, diamonds, and endodontic instruments be used once and discarded rather than re-sterilized. The rationale for this guidance is that disposable items eliminate the risk of patient-to-patient contamination. The guideline further recommends that single-use devices used during oral surgical procedures be sterile at the time of use [1] and that DHCP should refer to manufacturer instructions for use (IFU) to determine if a device is intended for single use. If a manufacturer does not provide validated reprocessing instructions (i.e., cleaning and disinfection or sterilization) the item should be considered single-use and disposable. [1] [13]

Available scientific evidence provides support for these recommendations. The sharp angles and irregular cutting surfaces of dental burs and diamonds and other rotary cutting instruments make them difficult to clean. [2-6] Morrison and Conrod examined the effectiveness of sterilizing brand new, never-used burs, and reprocessed burs that had been used on patients. They found that sterilization procedures were 100 percent effective for unused burs and unused files but that following sterilization, contamination rates ranged from 15 percent for one group of used burs to 58 percent for one group of used files. [7] Al-Jandan and colleagues compared new, unused burs and reused burs that were cleaned using standard protocols and then steam sterilized. New, unused burs were found to be 100% sterile after autoclaving whereas 5% of reused burs exhibited residual bacterial contamination. [4]

In addition to the challenge of removing organic soils, ultrasonic cleaning and steam autoclaving can damage cutting surfaces and raise the potential for breakage during patient treatment. [6-8] Von Fraunhofer and colleagues evaluated the effect of multiple uses of disposable diamond burs to cut lesions on extracted teeth and found increased leakage when burs were used more than three times. [9]

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies dental burs, diamonds, and endodontic instruments as regulated medical devices. The FDA over the last several years has been enforcing requirements for manufacturers to provide IFU’s that describe device reprocessing methods including removal of patient material including blood, tissue, and hard tissues (bone, dentin, and enamel) prior to sterilization. Unless a manufacturer has submitted a 510(k) submission that includes instructions for cleaning prior to sterilization, the FDA considers all diamond-coated burs and scaler tips single-use. [10]

To demonstrate that these items can be adequately cleaned, the FDA often accepts testing done using a national or international standard method published by a standards development organization such as the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) or the International Association for Standardization (ISO). [11- 12] There are standard methods to determine cleaning effectiveness for blood and soft tissue [12] but currently no standard method exists for removal of hard tissues from cutting surfaces of burs and diamonds making them by default, single-use devices.

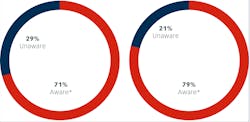

* Of total survey respondents, 28% said they were aware but lacked detailed knowledge.

Figure 2 right: Awareness of CDC recommendations regarding single-use burs, endodontic files, and broaches due to challenges in cleaning and heat sterilization, risk for deterioration of cutting surfaces and potential for breakage during patient treatment

* Of total survey respondents, 28% said they were aware but lacked detailed knowledge.

According to the FDA, a single-use or disposable device is intended for use on one patient during a single procedure. Labeling provided by manufacturers may not always identify the device as single-use or disposable, but if specific reprocessing instructions are not provided, the item is considered single-use and disposed of following federal, state, and local regulations.

While CDC has no authority to enforce compliance with their recommendations, and FDA regulations apply only to manufacturers of dental devices, following the manufacturer’s IFU is a best practice. Failure to do so may have medicolegal consequences if an adverse event, such as disease transmission or injury due to a device failure, occurs. In some institutional settings such as the military, Veterans Administration, Public Health Service, or practices subject to accreditation by organizations such as The Joint Commission, the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) and American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (AAAASF), CDC guidance and best practices from standards developers such as AAMI may be enforceable. Many dental boards in the U.S. require compliance with CDC recommendations or use them to make standard of care determinations.

If there are questions about product labeling and instructions for reuse, they should be directed to the manufacturer. The FDA also has a searchable database for dental products which have been cleared to market which is available at accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm.

Survey Results: Knowledge, Practice and Attitudes Among Dental Health Care Providers Regarding Single-Use of Dental Diamonds and Burs

We conducted an online survey of Dental Economics readers over two weeks in the summer of 2020 to gain an understanding of dental provider’s current knowledge, attitudes and practices related to use and reprocessing of burs, diamonds, and endodontic instruments.

The survey was conducted using a convenience sample solicited through the Dental Economics website. Respondents were entered into a drawing for a $100.00 gift card to thank them for their participation. A total of 130 DHCP responded to the survey.

Knowledge

We first asked questions to determine respondent’s awareness of the current CDC recommendations and FDA regulations regarding single use of dental diamonds. A clear majority (71%) were aware of the requirements with 28% having indicating awareness, but lack of detailed knowledge on the topic. A minority of respondents (29%) were unaware of the regulations (figure 1).

Awareness of CDC recommendations regarding single-use burs, endodontic files, and broaches due to challenges in cleaning and heat sterilization, risk for deterioration of cutting surfaces and potential for breakage during patient treatment was slightly higher, with 79% indicating awareness. Twenty-six percent however, said they lacked knowledge of the details. Fewer respondents, 21%, were unaware of the CDC recommendations when compared to 29% for the FDA regulations.

A group of survey questions asked respondents to tell us how they used and reused dental diamonds, burs, endodontic files, abrasive finishing points, mandrels, and other specialized rotary instruments. (For some of the questions below, and because respondents were asked to indicate all applicable responses, totals may exceed 100%.)

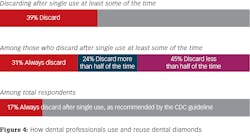

Among survey participants who used dental diamonds, 39% (50 of 127) indicated they discarded burs after a single use at least some of the time. Among respondents indicating that they discarded diamonds after single use, 31% (21 of 68) always did so, 24% (16 of 68) estimated that they did so more than half of the time while 46% (31 of 68) estimated doing so less than half of the time. When considered as a percentage of all respondents who answered this question, only 16% (21 of 128) always discarded dental diamonds after single use as recommended in the CDC guideline. When considered as a percentage of all respondents who answered this question adjusted for the number (2) who indicated that they did not use dental diamonds in the previous question, only 17% (21 of 127) always discarded burs after single use as recommended in the CDC guideline.

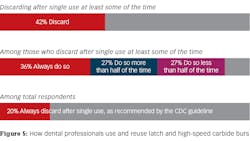

Forty-two percent of respondents (53 of 126) indicated they discarded latch and high-speed carbide burs after a single use at least some of the time. Among respondents indicating that they discarded diamonds after single use, 36% (25 of 70) answered “always”. Among those who said they discarded carbide burs after use at least part of time 37% (26 of 70) estimated that they did so more than half of the time while 27% (19 of 70) estimated doing so less than half of the time. When considered as a percentage of all respondents who answered this question, only 19% (21 of 126) always discarded burs after single use as recommended in the CDC guideline. When considered as a percentage of all respondents who answered this question adjusted for the number (3) who indicated that they did not use carbide burs in the previous question, only 20% (25 of 126) always discarded burs after single use as recommended in the CDC guideline.

Ultrasonic cleaners were the most widely used method for cleaning diamonds (69%) and burs (63%) followed by manual cleaning (diamonds 14%; burs 19%) and instrument washers (diamonds 9%; burs 10%).

Respondents were much less likely to discard abrasive finishing points, wheels, and mandrels than dental diamonds or burs with only 29% (36 of 124) indicating that they did so and only 7% indicating that they always did so. Among those who reported discarding these items after a single use, the participants were equally divided when asked if they do so always, less than half the time or more than half the time. Each category scoring 33% (17 of 51). When reused, percentages for methods of cleaning and sterilization were similar to those used for diamonds and burs.

Of 98 respondents that reported using endodontic files, 51% (50 of 98) indicated they discarded them after a single use at least part of the time. One respondent commented they reused files, but only for the same patient while another observed that they discarded files size 20 and under after a single use. When those that indicated they discarded endodontic files after a single use were asked how often they did so, 52% (35 of 67) responded “always”, 25% (17 of 67) did so more than half of the time, 22% (15 of 67) did so less than half of the time. When considered as a percentage of all respondents who answered this question adjusted for the number (32) who indicated that they did not use endodontic files in the previous question, only 36% (35 of 98) always discarded burs after single use as recommended in the CDC guideline.

Respondents were asked to tell us how they used and reused surgical burs. Of the 109 who reported using them, 56% (61 of 109) reported discarding burs after a single use at least part of the time. Methods of reprocessing were similar to those used for other items. When respondents who answered affirmatively regarding single use were asked how frequently they discarded burs after a single use, 65% (48 of 74) responded “always”, 23% (17 of 74) did so more than half of the time, and 12% (9 of 74) did so less than half of the time. When considered as a percentage of all respondents who answered this question adjusted for the number (20) who indicated that they did not use surgical burs in the previous question, 32% (35 of 109) always discarded burs after single use as recommended in the CDC guideline.

Sixty-five of 130 respondents indicated that they used implant drills or other specialized rotary instruments in their practices. Only 18% (12 of 65) said they discarded these burs after a single use at least some of the time. When reused, manual cleaning was employed by 29% (19 of 65) which is almost twice as frequently as for other items. When asked how frequently implant drills or other specialized rotary instruments were discarded after a single use, only 24% of (7 of 29) indicated always doing so. Thirty-one percent (9 of 29) did so more than half of the time while 45% (13 of 29) did so less than half of the time. When considered as a percentage of all respondents who answered this question adjusted for the number (65) who indicated that they did not use implant drills or other specialized rotary instruments in the previous question, only 11% (7 of 64) always discarded burs after a single use as recommended in the CDC guideline.

Attitude

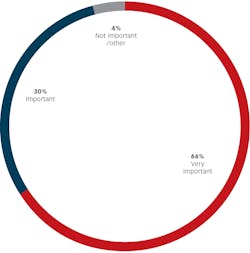

The next group of questions asked respondents to describe their attitude and rationale for their decision to reuse or discard patient care items after a single use. We asked respondents to tell us how important it was to follow manufacturer’s instructions for use when reprocessing dental devices. Almost all respondents (96% or 125 of 130) said it was “important” (30%) or “very important” (66%).

Respondents were asked the reasons for discarding burs after a single use. Fifty-six percent (72 of 129) of respondents indicated they discarded burs after a single use to decrease the risk that an instrument would have to be replaced during a procedure due to lack of effectiveness. The second most frequent response at 46% (59 of 129) was that due to extreme difficulty in cleaning these patient care items it is challenging to ensure they are sterile. Thirty-one percent (40 of 129) agreed that single use decreased risk of failure and potential aspiration or ingestion of dental items while 21% (27 of 129) felt that it lowered the risk of percutaneous injury during reprocessing. Almost 20% (25 of 129) chose single use due to it being cost effective when the monetary and time costs of reprocessing are considered.

Five percent of respondents answered “other’. These reasons included that some disposable items cannot be sterilized, that they use so few burs it is easier to do single use and that they only use reprocessed burs for denture/partial repairs or to roughen up surfaces for composite or crown repairs.

Respondents were then asked to select the best answer that described their rationale for reprocessing diamonds, burs, endodontic files and other items. The most frequently cited reason was cost with 48% (63 of 130) of respondents agreeing that the costs of reprocessing were offset by avoidance of the need to purchase new burs, diamonds, and endodontic instruments. Forty-six percent (60 of 130) agreed with the statement that they and/or their staff were comfortable with the safety and cost-effectiveness of reprocessing procedures and do not find them burdensome. Twenty-eight percent (37 of 130) of respondents indicated they felt that reprocessed items did not show residual contamination or deterioration and worked as well as when new. One respondent commented that they check all items under magnification after sterilization to determine safety for reuse.

Twenty-two percent (29 of 130) of respondents said they only reprocess expensive specialty burs, diamonds, or endodontic instruments and 13% (17 of 130) stated that they never reprocess these items.

Discussion

Nearly all respondents to this survey indicated that they had at least some awareness of CDC recommendations and FDA regulations related to instructions for use for dental diamonds, burs, or other items. There was also near unanimity among respondents affirming the importance of following manufacturer’s IFU. While most respondents reported discarding burs, diamonds, and other items after a single use at least part of the time, the percentage of respondents indicating full compliance with CDC guidelines for single use ranged from 20% for dental burs to 11% for implant and other specialty items.

Both in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated residual contamination, and in some studies, survival of microorganisms on burs following standard reprocessing methods including both manual and ultrasonic cleaning. [2-5] Standard reprocessing procedures have also been shown to cause loss of diamond particles [8] and pitting on carbide burs [6] including those not previously used on patients. Burs and other items may also exhibit surface patination or corrosion that if viewed by a patient may influence their behavior as consumers of healthcare.

Ultrasonic cleaning was the most widely used method among respondents for re-processing used burs, diamonds, and other items. Vassey and colleagues compared the effectiveness of manual cleaning, manual cleaning combined with ultrasonic cleaning, and an automated washer/disinfector, for removal of residual protein (used as a marker for biological contamination) on a range of dental instruments including burs. Manual cleaning combined with ultrasonic use was significantly less effective in removing residual protein than either manual cleaning alone or cleaning with the automated washer/disinfector. [1] One possibility for this finding not stated by the authors is that ultrasonic solutions may be infrequently changed, and instruments inadequately rinsed before packaging and sterilization. The authors noted that the wide range of variation of residual contamination seen in the study underlies the complexity of this process.

Cleaning and sterilization of burs and diamonds including unused burs placed in bur blocks have also been shown to decrease cutting and polishing efficiency when compared to new burs. Despite these findings, most respondents in this survey were satisfied with the clinical performance and perceived safety of reused burs, diamonds, and other items. In contrast, respondents who discarded items after a single use at least part of the time agreed that difficulty in cleaning, lack of sterility assurance and potential for device failure were factors favoring single use.

Since surgical burs may have the greatest risk for disease transmission if not adequately cleaned, it is somewhat reassuring that six out of ten respondents reported always discarding surgical burs after a single use. Specialty burs, such as those used in implant placement, also may have greater potential for disease transmission but were the least likely of all items to be discarded after a single use.

It should not be surprising that economic considerations topped the list of reasons for reusing burs, diamonds, and other items, with concerns about the cost of purchasing new inventory being foremost among these. This was also reflected by the fact that more costly items such as specialty burs and endodontic files were more likely to be reused than other items. When acquisition costs are considered as the sole justification for reuse it is obvious that using more items will increase costs for the practice. But does this calculation accurately assess the real cost of reuse when all costs are considered, and the rubric of risk/benefit is applied to the problem?

To understand the real costs associated with reprocessing difficult-to-clean items like burs and diamonds, the entire life cycle of the item and associated expenses in time and money must be considered. This can be done by conducting a risk-benefit analysis to include direct costs, indirect costs, and cost avoidance considerations.

Direct costs include purchase of bur blocks, instrument wraps and process indicators. Indirect costs include the time and effort expended by dental team members restocking depleted bur blocks, cleaning, inspecting, and wrapping used items, and loading, operating, and emptying the sterilizer. Reducing the number of loads run can also produce savings over time in both utility and maintenance/replacement costs for instrument cleaning and sterilization equipment. While some of these costs will be subsumed by the inclusion of bur blocks in the reprocessing stream for other reusable items, their elimination may still result in savings over time.

Currently there are many affordable options for purchasing sterile single-use burs and diamonds. Studies comparing single-use and multi-use diamonds and burs have found little difference in performance for individual procedures. [13-14] Since at least one study found viable microorganisms in “factory clean” but non-sterile burs, choosing items that are in sterile packaging should also be considered. Burs used for surgical procedures or that may penetrate mucous membranes are considered critical items by CDC and must be sterile as a condition of use. [1] [15]

From a personnel management perspective, decreasing the time and effort required of dental team members to manage these difficult-to-clean items can clear them for other potentially revenue-generating tasks, and may also improve staff morale. Unit dosing of new burs, diamonds or other items also ensures greater cutting or polishing efficiency that can decrease instances when a procedure is interrupted to replace a worn-out or broken item. More importantly, single use eliminates the need for unnecessary DCHP contact with contaminated items. Percutaneous injury leads to post-exposure management, additional medical costs associated with seroconversion, and potential Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) citations.

Patient-associated cost avoidance considerations should also be included in any risk-benefit analysis. Dental items that have been reprocessed without specific instructions for use from the manufacturer may pose a greater liability risk in the event of an adverse outcome such as patient-to-patient disease transmission due to inadequately cleaned and sterilized items, ingestion or aspiration of a broken instrument, broken endodontic files in root canals, and other soft or hard tissue injuries. When IFU’s are not followed, manufacturers may be able to shift some or all of the burden of responsibility for a device-related adverse outcome to the end user.

Finally, as dental professionals we are obligated to put the safety and health of the patient foremost. This requires us to make our best effort to remediate known risks that may result in patient injury or illness.

Conclusions

Since 2003, the CDC has advised dentists to implement single use and disposal of burs, diamonds, and other difficult-to-clean dental instruments. Published studies reveal that residual contamination is frequently present on burs and diamonds following standard cleaning methods and that in some cases this can result in sterilization failure as well. The FDA has determined that manufacturers must consider their devices to be single-use disposable unless they provide laboratory validated cleaning and sterilization protocols.

When asked how important it is to follow guidelines and manufacturer’s instructions for use when reprocessing dental devices, including burs, diamonds, and endodontic instruments, nearly all respondents (96%) said it was important or very important. This stands in contrast to the reprocessing practices reported by most survey participants with the percentage of respondents indicating full compliance with CDC guidelines for single use ranging from 20% for dental burs to 11% for implant and other specialty items. While the potential risks described in this article may not be easily quantifiable, conforming to current CDC guidelines is achievable and may provide additional benefits in terms of risk avoidance, clinical efficiency, team morale and patient satisfaction.

References

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings--2003. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003;52(RR-17):1-61

- Vassey M, Budge C, Poolman T, et al. A quantitative assessment of residual protein levels on dental instruments reprocessed by manual, ultrasonic and automated cleaning methods. Br Dent J 2011;210(9):E14 doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.144[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Sajjanshetty S, Hugar D, Hugar S, Ranjan S, Kadani M. Decontamination methods used for dental burs - a comparative study. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8(6):ZC39-41 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9314.4488[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Al-Jandan BA, Ahmed MG, Al-Khalifa KS, Farooq I. Should Surgical Burs Be Used as Single-Use Devices to Avoid Cross Infection? A Case-Control Study. Med Princ Pract 2016;25(2):159-62 doi: 10.1159/000442166[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Gul M, Ghafoor R, Aziz S, Khan FR. Assessment of contamination on sterilised dental burs after being subjected to various precleaning methods. J Pak Med Assoc 2018;68(8):1188-92

- Villasenor A, Hill SD, Seale NS. Comparison of two ultrasonic cleaning units for deterioration of cutting edges and debris removal on dental burs. Pediatr Dent 1992;14(5):326-30

- Morrison A, Conrod S. Dental burs and endodontic files: are routine sterilization procedures effective? J Can Dent Assoc 2009;75(1):39

- Pilcher ES, Tietge JD, Draughn RA. Comparison of cutting rates among single-patient-use and multiple-patient-use diamond burs. J Prosthodont 2000;9(2):66-70

- von Fraunhofer JA, Smith TA, Marshall KR. The effect of multiple uses of disposable diamond burs on restoration leakage. J Am Dent Assoc 2005;136(1):53-7; quiz 90 doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0026[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Medical Devices; Reprocessed Single-Use Devices; Termination of Exemptions From Premarket Notification; Requirement for Submission of Validation Data. Federal Register: U .S. Food and Drug Administration 2003.

- Reprocessing Medical Devices in Health Care Settings: Validation Methods and Labeling Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff: US Food and Drug Administration 2015.

- Working Together to Improve Reusable Medical Device Reprocessing. Secondary Working Together to Improve Reusable Medical Device Reprocessing July 16, 2018 2018. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/reprocessing-reusable-medical-devices/working-together-improve-reusable-medical-device-reprocessing.

- Roeder LB, Powers JM. Surface roughness of resin composite prepared by single-use and multi-use diamonds. Am J Dent 2004;17(2):109-12

- Ercoli C, Rotella M, Funkenbusch PD, Russell S, Feng C. In vitro comparison of the cutting efficiency and temperature production of 10 different rotary cutting instruments. Part I: Turbine. J Prosthet Dent 2009;101(4):248-61 doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60049-4[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Single-Use (Disposable) Devices. Secondary Single-Use (Disposable) Devices April 27, 2018 . https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/faqs/single-use-devices.html

KAREN DAW, MBA, CECM, “The OSHA Lady,” is an award-winning speaker, consultant, and author of articles and CE courses on safety in dentistry. Learn more about her at karendaw.com.

SHANNON MILLS, DDS, is a consultant and lecturer who is internationally recognized as an expert in dental infection prevention, dental industry standards development, and patient-centered dental benefits.

About the Author

Karen Daw, MBA, CECM

Karen Daw, MBA, CECM, “The OSHA Lady,” is an award-winning speaker, consultant, and author of articles and continuing education courses on safety in dentistry. Learn more about her at karendaw.com.