Making dental composites better and longer lasting

I am somewhat discouraged with resin-based composite restorations. After placing composite for many years, I have concluded that the restorations look very good at placement, but only a few years later I am frustrated when I see margin breakdown, new caries, and often open contacts. What can I do to make these restorations last longer and serve better?

You are correct in your observations about composites. It is seldom that any of us see impressive composite restorations several years after their placement. Some of the challenges are related to the characteristics of the material, and others are related to clinical techniques. In this article I will address both of these issues and provide some potential solutions.

Resin-based composite material challenges

I have practiced dentistry through the complete history of dental composites, and I’ve seen and suffered through the various early dilemmas related to this restorative material. If you think the current composites are a problem, you should have seen the early ones from 60 years ago.

High-wear characteristics of the composite would collapse due to occlusion, occlusal prematurities, and some temporomandibular disorders. After a few months, the composite surface was rough—not only to the eye, but to the tongue as well. The particle size of the filler was nearly 10 times the diameter of a typical human hair. This problem has been overcome by manufacturers placing nano-size particle fillers in restorative composites. Most current composites wear remarkably similar to enamel.

Early on, it was difficult to obtain tight contact areas with adjacent teeth, largely because dentists were using the old variety of Tofflemire matrices. As a result, they were having problems such as flat open contacts, food impactions, and subsequent caries. This has been overcome by more sophisticated sectional matrices and modified matrices such as the Greater Curve Tofflemire, which, when tightened, actually moves the band toward the contact area. Wedging has also improved.

Postoperative tooth sensitivity was a major problem at the time, and many composite restorations of that era soon required endodontic treatment. This problem has not been completely overcome, since some practitioners still complain about sensitivity. But it is possible to overcome this challenge nearly completely.

Color change occurred during the service of early composites, since the first brands were only autocured. Tertiary amine was also used as the resin activator, which caused subsequent yellowing of the restorations.

To summarize the previous undesirable original materials characteristics, early composites were not a viable replacement for the most-used amalgam restorations of the day. Let’s look at where composite materials are now and go through a composite procedure.

Remaining challenges with composite materials

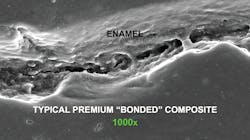

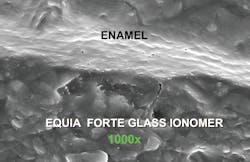

Shrinkage of the composite material on polymerization: Most current resin-based composite materials are (1) modifications of the original bis-GMA resin that was brought into dentistry in the early 1960s, (2) urethane dimethacrylate, or (3) combinations and new iterations of those materials. The resin is the vehicle that holds the microscopic filler particles together. But these resins shrink on polymerization at an average of about 2%. Microscopic observation of composite/tooth margins on any composite restoration shows microscopically open margins that are frustrating to see and potentially problematic (figure 1). Although many companies have attempted to reduce or eliminate the shrinkage, with some progress having been made, resin shrinkage is one of the major reasons for clinical composite failure. Conventional glass ionomer provides a chemical chelation to the tooth structure without marginal voids (figure 2).What is the problem with shrinkage? To a microbe, the margin of a composite is essentially similar to a wide-open freeway on which you are driving your car. The word “seal” for composite is a misnomer. Composite margins allow mouth fluids, food debris, and microbes to freely move into the internal areas of the tooth preparation. There is a technique that can reduce this problem.

Postoperative tooth sensitivity: As stated previously, postoperative tooth sensitivity remains a problem for some dentists, and this is related to the composite material. This is a problem that can be reduced or eliminated.

Lack of cariostatic properties: Composite resin does not have cariostatic properties and must be placed nearly perfectly to avoid subsequent caries. Several companies are showing progress in making cariostatic composite restorations, but caries around previously placed restorations is still a significant problem. There is a technique, however, that can help.

Overcoming or reducing remaining clinical challenges with composite

Composite restorations can be a difficult procedure, particularly those involving large ones: The restoration must have acceptable contact areas, appropriate desensitization, proper disinfection, acceptable margins, matching tooth color, and acceptable occlusion. How can these goals be achieved? Small restorations require only a fraction of the time that large restorations require.

There is no question that current digital radiographs are not capable of showing small carious lesions. I suggest using concepts such as the Microlux or the CariVu transilluminators in addition to digital radiographs to locate small, interproximal carious lesions. Restoring small lesions greatly reduces the difficulty of accomplishing your clinical goals.

Composites can be time-consuming compared to other procedures: A small class II composite restoration can be accomplished by an experienced, competent dentist in a short time, while a large restoration requires much more time. For your conscientious and hygiene-compliant patients, finding and restoring small lesions are relatively easy tasks. Encourage as many patients as possible to come in for regular recall appointments to reduce the development of large lesions and the time necessary to treat them.

Low revenue: Unfortunately, and in spite of the difficulty of some composite restorations, the fees for them are low. Many other clinical procedures requiring less time and effort have higher average fees. We cannot eliminate this challenge. I suggest that you educate your dental assistants to the level that they know the composite procedure as well as you do and have all of the materials and devices ready for scheduled procedures. I also suggest using a second dental assistant during this time-consuming procedure. Research has shown that the addition of a second assistant—six-handed dentistry—can speed up most procedures by up to 40%.

Obtaining tight contact areas: This is still a problem for some dentists. Use sectional matrices such as Garrison, Triodent, Dentsply Sirona, Ultradent, and others to obtain tight contact areas.

Tooth sensitivity: Proper use of desensitizers and occasionally liners can eliminate this problem.

Subsequent caries: Proper disinfection and placement of cariostatic dentinal replacements can greatly reduce this problem.

Short longevity: Incorporating the previous concepts into your practice will increase the longevity of your composite restorations.

Suggested clinical procedure for composite restorations (class I and II composites)

If you aren’t using these procedures, we have videos that will guide you through the process. On the other hand, if you are satisfied with the results of what you are doing currently, stay with that technique.

Composite placement technique for small tooth preparations

- Identify carious lesions as soon and when they are as small as possible.

- Anesthetize the patient.

- Make a dry field, preferably with a rubber dam (Isolite 2, Mr. Thirsty One-Step, or others).

- Make the prep as small as possible with a carbide or diamond bur. I suggest the following sizes: premolar isthmus width and proximal box with 329 bur; a molar with a 330 bur.

- Acid-etch the prep with your preferred method—total, selective, or self-etch. I prefer selective enamel etch.

- Wash and dry the prep.

- Place glutaraldehyde-containing desensitizer/disinfectant for two one-minute applications (MicroPrime, G5, Glu/Sense, Gluma, or others—5% glutaraldehyde and 35% HEMA). Don’t wash off; suction off instead.

- Place a bonding/wetting agent of your choice (Scotchbond Universal or many others), blow thin, and cure.

- Repeat step no. 8 if there is any question that you did not place bond on all of the prep.

- Place and cure the resin of your choice, preferably in only 2 mm increments.

- Finish the restoration.

- Evaluate and adjust the occlusion.

Composite placement technique for deep tooth preparations

- Identify caries as soon as possible and plan to conserve as much tooth structure as possible.

- Anesthetize the patient.

- Make a dry field, preferably with a rubber dam (Isolite 2, Mr. Thirsty One-Step, or others).

- Make the prep as small as possible with a carbide or diamond round-ended bur the size of an 1156 or 1157, leaving stained tooth structure internally if it feels hard to a spoon excavator. If possible, avoid exposing the pulp.

- Place glutaraldehyde-containing desensitizer/disinfectant for two one-minute applications (MicroPrime, G5, Glu/Sense, Gluma, or others—5% glutaraldehyde and 35% HEMA). Don’t wash off; suction off instead.

- Assuming the prep was moderately deep and close to the pulp, place at least a 0.5 mm thick liner (Vitrebond Plus, Fuji Lining Cement, Ultradent MTA Flow).

- If the prep was very deep and might potentially develop subsequent caries, place Equia Forte or Ketac Universal, the new generation of glass ionomers, as a thick layer to replace the dentin.

- Acid-etch the prep with your preferred method—total, selective, or self-etch. I prefer selective enamel etch.

- Again, place glutaraldehyde-containing desensitizer/disinfectant for only a few seconds, since you washed off the previous layer of glutaraldehyde under the liner or base. Don’t wash off; suction off instead.

- Place a bonding/wetting agent of your choice (Scotchbond Universal or many others), blow thin, and cure.

- Repeat step no. 10 if there is any question that you did not place bond on all of the prep.

- Place the resin of your choice, preferably in only 2 mm increments, and cure.

- Finish the restoration.

- Evaluate and adjust the occlusion.

Summary

Composite restorations do not have to be difficult and short-lived. Using the procedures suggested in this article will reduce or eliminate your problems with composite materials.

Author’s note: The following educational materials from Practical Clinical Courses offer further resources on this topic for you and your staff.

New three-hour streaming courses:

- Predictable, Fast, Long-lasting Composites (item no. V3512)

- Returning to Dental Practice in the New COVID-19 World (item no. V2407)

One-hour videos, streaming or on DVD:

- Mastering Frequent Esthetic Challenges with Resin (item no. V3582)

- Making Foolproof Class II Composites (item no. V3501)

For more information about these educational products, call (800) 223-6569 or visit pccdental.com.

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD, is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah. He is the founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing education organization founded in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is cofounder (with his wife, Rella Christensen, PhD, RDH) and CEO of Clinicians Report.

About the Author

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD

Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, PhD, MSD, is founder and CEO of Practical Clinical Courses and cofounder of Clinicians Report. His wife, Rella Christensen, PhD, is the cofounder. PCC is an international dental continuing education organization founded in 1981. Dr. Christensen is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah.