A business model to calculate revenue resulting from implementation of a child oral health program

Caries remains the most common chronic childhood disease, five times more common than asthma and 20 times more common than diabetes.1 While pediatric dentists are specially trained to prevent and treat this disease in children, general dentists currently outnumber pediatric dentists 20:1; thus the safety net for children’s preventive oral health often lies with general dentists.2 While most general dentists believe at-risk one-year-old children need a dental home, less than half of them are willing to accept these patients into their practices.3

Reasons cited for this contraindication are discomfort and inexperience with small children, office disruption due to children crying, and inadequate reimbursement.4 I, along with my research team Sigurdur Saemundsson, DDS, MPH, MBA, PhD, Rocio Quinonez, DMD, MPH, MS, and Bradley Staats, DBA, MBA, created a project that aimed to address the latter argument—the lack of reimbursement. To accomplish this, we developed a customizable business model in which general dentists can use their own practice parameters to assess how incorporating a child oral health-care program would financially affect their practices.

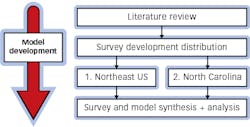

We developed a customizable business model with 10 input values. To determine these input values in a practice setting, we developed and distributed a survey to practicing general dentists. We used these survey result values as input for the model. Lastly, we performed a sensitivity analysis of the 10 model inputs. The bulk of our project consisted of developing the customizable business model, with the first step to determine what inputs to include, as depicted in Figure 1.

Specifically, we aimed to determine what practice characteristics could influence income gained from incorporating a child oral health program. As a note, bOHP, Baby Oral Health Program, is a program that was developed at The University of North Carolina.5 Its function is to provide practitioners with the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to confidently treat the youngest patients. Throughout this article, the bOHP abbreviation will be used to represent a practice that is beginning to incorporate a child oral health program. Along with our business colleagues, we identified 10 input values that would shape and inform the model, with brief descriptors of each, shown in Table 1.

As the goal of seeing the bOHP patients so early is to prevent dental disease altogether, the bOHP patient fee schedule consisted of preventive services only, and the bOHP patient roof, or maximum amount of bOHP patients, was found by multiplying input 1 (capacity for new patients per week) by input 2 (weeks practiced per year). Since the referral patients could be anyone, the fee schedule is based on the “average patient worth” in a general dental practice.

Based on a literature review, the average worth of $650 was established.7-11 The referral patient roof is set by input 10, or the number of patients until a practice is at maximum capacity. To model the uncertainty in everyday practice, we incorporated a Monte Carlo simulation in the model. The inputs were randomized via distributions found within the survey, allowing us to run the simulation 1,000 times, resulting in different iterations of inputs and thus different results each time. The next step was to synthesize the model and the survey results, followed by their input into the model. Lastly, we ran a sensitivity analysis of the 10 input values to determine which input most greatly affected financial returns.

Results

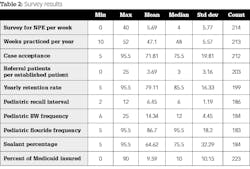

The first survey was sent to 3,102 practicing dentists. Of these, we received 47 unique responses, for a response rate of 1.52%. The second survey was sent to 4,000 practicing dentists. Of these, we received 212 unique responses, for a response rate of 5.30%. The survey results are listed in Table 2.

To determine the financial benefit from seeing these bOHP patients in the average general dental office, we input the survey’s mean results and entered them into the model as inputs 1 through 9. Input 10, reflecting patients until maximum capacity, was used to help define the referral patient ceiling and was not asked in the survey. The maximum capacity was arbitrarily set at 200 based on a review of the literature. According to practice management literature, the average general dentist needs 15 to 20 new patients per month.11 As there are 12 months in a year, this means the average general dentist needs 180 to 240 new patients per year, which is how we arrived at 200 patients per year. However, like all inputs, this is completely customizable.

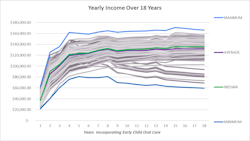

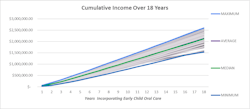

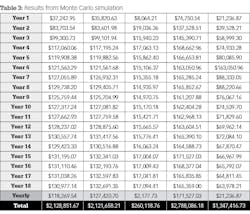

Table 3 depicts the results from inputting these 10 values into the model. Two graphs follow (figures 2 and 3) that depict the yearly added income after incorporating such a program, as well as the cumulative added income after incorporating such a program. The average financial gain from incorporating a program such as bOHP for one year is $37,243. At year six, this jumps to $121,563, at year nine it jumps to $125,759, at year 15 it’s $231,195, and at year 18 it’s $130,977. The average yearly financial gain is $118,270. To summarize, after 18 years of incorporating a child oral health-care program, the average financial gain is $2,128,852, with the maximum gain at $2,788,086 and the minimum gain at $1,347,147.

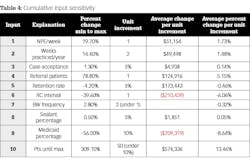

We did sensitivity analysis for each input by running the simulation 10 times while changing the desired input at equal intervals. While running each simulation, we kept all other inputs stagnant, like the averages found within the survey. The single output chosen for each iteration was the average total income over 18 years. The cumulative input sensitivity analysis is shown in Table 4. As you can see, input 10, which is used to form the referral patient roof, affects the model the most. For every 50 patients, the referral patient roof is raised and income is increased 13.46%.

The overarching goal of this project was to develop a customizable business model template that general dentists could use to help them decide whether to incorporate a child oral health-care program. Realism was built into the model via two separate patient roofs, randomization of the inputs, and incorporation of a Monte Carlo simulation. The purpose of the model was to be completely customizable, and the survey was used to provide practitioners with default inputs if a provider was unsure of any practice characteristics.

The model demonstrated that incorporation of a child oral health-care program in a practice where capacity exists can be financially beneficial, and can bring in an additional $2 million over 18 years. Furthermore, not all inputs were created equal, and some affected profits more than others, in particular input 10—patients until maximum capacity, or the referral patient roof.

1. Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Vital Health Stat 11. 2007;248(4):1-92.

2. Supply and profile of dentists. American Dental Association Health Policy Institute Data Center. February 2020. https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/data-center/supply-and-profile-of-dentists

3. Long CM, Quinonez RB, Rozier RG, Kranz AM, Lee JY. Barriers to pediatricians’ adherence to American Academy of Pediatrics oral health referral guidelines: North Carolina general dentists’ opinions. Pediatr Dent. 2014;36(4):309–315.

4. Garg S, Rubin T, Jasek J, Weinstein J, Helburn L, Kaye K. How willing are dentists to treat young children? J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(4):416-425. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0135

5. Virtual baby oral health program. https://www.babyoralhealthprogram.org/

6. Gupta N, Yarbrough C, Vujicic M, Blatz A, Harrison B. Medicaid fee-for-service reimbursement rates for child and adult dental care services for all states, 2016. American Dental Association. April 2017. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0417_1.pdf

7. Kareem. Dental patient worth? 75% of dentists don’t know value of a new patient. Uptime Houston. May 23, 2016. https://uptimehouston.com/how-much-is-a-new-dental-patient-worth/

8. Lavery W. What should I pay for a new dental patient? Patient News. September 3, 2016. https://patientnews.com/about-us/blog/what-should-i-pay-new-dental-patient/

9. What’s the lifetime value of a new dental patient? Dental Marketing Guy. March 7, 2016. https://dentalmarketingguy.com/lifetime-value-new-dental-patient/

10. Zilko A. Know the value of your patients, Dental Practice Marketing. https://www.firegang.com/do-you-know-the-lifetime-value-of-your-dental-patients/

11. Fettig D. Dental benchmarks: The numbers that matter: Benchmarking your dental practice—The key measure for success. Events Cloud. 2017. https://na.eventscloud.com/file_uploads/671823b21a962ff9d349ff281be06d5a_L106_Fettig-Benchmarks.pdf

MORGAN C. BIDDLE, DDS, MS, is a board-eligible pediatric dentist. She graduated from the University of Iowa College of Dentistry in 2017. After dental school, she moved to North Carolina and obtained a certificate in pediatric dentistry and a master’s in science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, graduating in 2020. She then joined a private practice in Holland, Michigan, where she is currently practicing.

About the Author

Morgan C. Biddle, DDS, MS

MORGAN C. BIDDLE, DDS, MS, is a board-eligible pediatric dentist. She graduated from the University of Iowa College of Dentistry in 2017. After dental school, she moved to North Carolina and obtained a certificate in pediatric dentistry and a master’s in science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, graduating in 2020. She then joined a private practice in Holland, Michigan, where she is currently practicing.