Ergonomic interventions in dentistry: Establishing a program for success, and why it matters

Key Highlights

-

Dentistry carries a high risk of musculoskeletal disorders, making early and continuous integration of ergonomic principles essential for career longevity and quality of life.

-

Effective ergonomic programs are built on four pillars: biomechanics, magnification technology, properly designed stools, and efficient four-handed dentistry.

-

Sustainable change requires top-down leadership, ongoing risk assessment, and evidence-based interventions embedded in dental education and daily practice.

Dentistry is a highly demanding health-care profession that exposes practitioners to an elevated risk of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). Contributing risk factors include prolonged static postures, awkward positioning, and the repetitive nature and duration of dental procedures—all occurring under time constraints in a complex clinical environment.

It is critically important that practitioners integrate ergonomic principles and interventions early in dental education and throughout professional practice. Such integration is essential for preventing and mitigating the long-term physical consequences that can compromise clinical performance, quality of life, and career longevity.

Ergonomics—the science of adapting work to the human body rather than forcing the body to adapt to work1—is particularly relevant to dentistry, a profession marked by physical and mental demands. The prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) among dentists continues to rise, often leading to chronic pain, reduced productivity, absenteeism, and—in severe cases—early retirement.2,3

Given the financial and personal investments associated with dental education and practice—including significant student debt, operational costs, and the pressure for clinical excellence4—there is an urgent need for a paradigm shift. Ergonomics and human factors should be foundational components of the dental curriculum from the outset.

Sustainable career performance in dentistry requires more than technical proficiency. It demands a holistic approach encompassing physical well-being, cognitive efficiency, interpersonal communication, and emotional resilience. For ergonomic programs to be successful, they must be championed from the top down, involving administrative leadership, faculty, and students in a shared commitment to healthier work practices.

The foundations of dental ergonomics: Four core pillars

A comprehensive ergonomic intervention strategy in dentistry can be structured around four key components:

- Understanding human biomechanics

- Utilization of ergonomic loupes and dental microscopes

- Incorporation of ergonomically designed stools

- Implementation of four-handed dentistry

Each of these pillars is vital to promoting efficient, sustainable, and injury-free clinical practice.

Biomechanics of the human body: Biomechanics, a subdiscipline of ergonomics, examines how posture and movement affect health. Dental professionals are particularly vulnerable to WMSDs due to numerous factors, including5:

- Awkward and static postures

- High-frequency motions

- Precision-driven visual and manual tasks

- Patient and equipment management

- Lack of visual access requiring indirect vision

- Inadequate team coordination

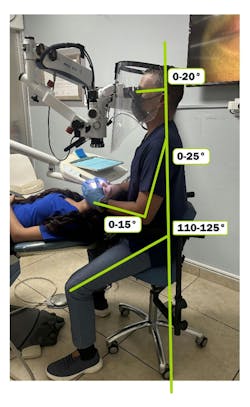

Failure to manage these risk factors early—during the formative years of training—can result in the development of maladaptive behaviors and chronic injury. Emphasis on maintaining a neutral posture is critical (figure 1). Ideal positioning includes6:

Head tilt: 0°-20° downward

Shoulder flexion: 0°-25° forward

Forearm angle: 0°-15° upward

Hip angle: 110°-125°

Empowering students with postural awareness and understanding of biomechanical principles is crucial for fostering safe habits and minimizing physical strain. Adopting a proper positioning sequence not only reduces compression forces on the joints during static postures, but also enhances the dentist’s ability to achieve optimal visual angles in the oral field.

This practice streamlines workflow and strengthens collaboration with dental assistants, ultimately promoting a more efficient and effective working environment. Emphasizing these guidelines will lead to greater comfort and productivity for both the dental professionals and their patients.

Ergonomic loupes and dental microscopes: Modern ergonomic loupes have significantly advanced postural alignment through the use of angled prisms that maintain the operator’s head and neck in a neutral position. These tools also serve as stepping stones for transitioning to the use of dental microscopes.7

Microscopes—originally introduced in endodontics in the 1990s—are now embraced across all dental disciplines due to their unparalleled magnification and coaxial, shadow-free lighting. Research shows that their use encourages neutral postures, reduces unnecessary movement, and supports the principles of four-handed dentistry. Additionally, microscopes with integrated cameras provide teaching and communication benefits for both clinical and educational settings.8

Integrating dental microscopes into dental school curricula—beyond just the endodontics program—would significantly enhance students’ work practices from the very beginning of their education. This approach would positively influence the learning curve, work habits, hand-eye coordination, and overall posture of students, fostering beneficial behaviors and habits for their future careers.

Implementing proper technology usage interventions, such as ergonomic loupes and microscopes designed with ergonomic principles in mind, would improve individual interactions within the human-technology system.

The ergonomic stool: Despite widespread use, most industrial stools supplied with dental units lack proper ergonomic design. Essential features for ergonomic stools (figure 2) include:

- Convex backrests for lumbar support

- Seats with a negative tilt for hip openness

- Armrests to reduce upper body fatigue during precision work

Such design elements have been shown to decrease muscle activity in the neck, shoulders, and lower back-areas commonly affected in dental professionals.9,10

During the intervention, engineering controls that analyze the items most frequently used in the office are among the most effective options for controlling risks and hazards. Evaluating the stools that dentists and assistants use throughout their long work hours is crucial for ensuring comfort and promoting a sustainable career. As practitioners, we spend over six hours a day in contact with our stools, making it essential to invest in a stool with the proper features. This investment helps protect the hips, lumbar region, shoulders, neck, and arms from fatigue by providing the necessary support to counteract the forces acting on our joints.

Work practices and four-handed dentistry: Possessing ergonomic tools is insufficient if not paired with proper work habits. Dentists must be trained to adopt motion-efficient workflows, minimizing unnecessary or repetitive movement.

One critical concept is horizontal reaching, a principle recognized by OSHA and NIOSH in industrial settings but often overlooked in dental education.11 Instruments should be organized based on frequency of use, and placed within zones that correspond to reach categories (constant, frequent, occasional). This reduces strain and improves procedural efficiency.

In environments where student dentists work without assistants, procedural trays can still be preorganized to reflect these principles. Early adoption fosters lifelong ergonomic awareness and prepares students to educate future assistants effectively.

Mirror use and indirect vision are additional ergonomic tools that should be emphasized. Mastery of indirect vision is essential for efficient microscope use and postural health for the operator, allowing for nearly continuous magnified visualization during treatment and decreasing muscle activity, and sitting balance, which may correlate with the reduction or prevention of MSDs.12

Ergonomic interventions, based on observational evaluations, can help measure several factors related to a practitioner’s movements. These include the duration, frequency, and intensity of their actions, how the dentist holds instruments, wrist deviation, overall posture, and working behaviors in relation to their assistant. The assistant’s role is a key component of the ergonomic circuit.

By analyzing how the assistant and dentist preorganize items and their placement strategies—considering principles of horizontal reaching by zones, assistant positioning, and transferring skills—we can protect the dentist both physically and cognitively. This organization allows the dentist to focus exclusively on their tasks without interruptions or unnecessary motions.

Program implementation and evaluation

The successful implementation of ergonomic programs requires administrative support and leadership. A simple yet powerful tool for program initiation is the use of surveys. Structured questionnaires can assess posture habits, ergonomic awareness, and early symptoms of WMSDs.13

These surveys collect data on:

- Duration and frequency of awkward postures

- Static positioning and force exertion

- Motion frequency and repetition

- Tool and workstation design

- Perceived discomfort or task-related pain

When paired with observational tools (e.g., photogrammetry), surveys help identify risk-prone behaviors and guide intervention strategies.14-16

Indicators of MSD risk may include those who:

- Regularly express discomfort or fatigue

- Modify equipment or workstations independently

- Wear braces or splints

- Frequently massage or shake limbs during tasks

- Avoid specific procedures due to pain

A well-structured ergonomic checklist should assess not only individual postures and forces but also:

- Instrument placement and horizontal reach zones

- Assistant integration and four-handed techniques

- Mirror and magnification use

- Stool adjustment practices

Tools commonly used for ergonomic risk assessment that can be utilized by ergonomists include the Washington State Ergonomic and MSD Risk Assessment, WISHA Hazard Zones Job Checklists, Worker Discomfort Survey, Perceived Exertion Survey, RULA, Rodgers Muscle Fatigue Analysis, Strain Index (SI), and advanced software such as the 3DSSPP developed by the University of Michigan, as well as exoskeletons and postural sensors.

These ergonomic tools provide a wide range of information regarding the risk of developing MSDs, prioritizing changes, analyzing working patterns, assessing postural information, evaluating compression forces, conducting fatigue analysis based on work cycles, and performing task analysis, among other important data. This information is essential for controlling, preventing, minimizing, or eliminating potential hazards faced by dental workers.

Ergonomic interventions in high-risk environments such as dentistry must be proactive. Risk assessments, control strategies, continuous monitoring, and

evidence-based guidelines are essential for cultivating a healthier, more sustainable workforce.17

By implementing regular evaluations and follow-ups-using methods such as the Deming cycle or Lean Six Sigma processes, we can assess and enhance the level of practice in dental schools and private practices. Utilizing the Hierarchy of Controls to systematically minimize risks, ranging from personal protective equipment and administrative controls to the most effective engineering controls, serves as a foundation. Coupled with ergonomic assessment tools, this approach can lead to improved health and safety practices for the dental team.

Conclusion

The implementation of ergonomic principles in dental education and practice, based on solid evidence, can be truly transformative. By integrating ergonomics from the earliest stages of training, dental schools can develop practitioners who are not only clinically skilled but also physically resilient.

A commitment from the top-engaging administration, faculty, and students is essential to instill habits that promote optimal posture, teamwork, effective use of technology, and a focus on prevention. In the long run, these efforts can help protect against the physical toll that often shortens promising dental careers.

Without an ergonomic education and intervention program, the possibility of changing the high rates of musculoskeletal disorders or burnout among dental professionals is minimal. Consistent commitment from management within the organization is a key factor in developing behavioral shifts. Additionally, providing regular feedback from ergonomic assessments obtained through interventions can help tailor a holistic approach for change, leading to gradual and positive shifts in both general practices and individual habits.

As I have learned firsthand, prevention is usually the most effective remedy.

Editor's note: The article appeared in the January 2026 print edition of Dental Economics magazine. Dentists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Garner et al. Ergonomics in work system design enhancing worker productivity and safety. Int J Sci Res Archive. September 2023.[KB5]

- Gupta A, Bhat M, Mohammed T, et al. Ergonomics in dentistry. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2014;7(1):30-34.

- Lobo WMV, Sayed A, Kadam AS, Sapkale K. Beyond the chairside: a narrative review of ergonomic practices in dentistry for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorder. IP Indian J Conserv Endod. 2024;9(1):15-19.

- Boyles JD, Ahmed B. Does student debt affect dental students’ and dentists’ stress levels? Br Dent J.2017;223(8):601-606.

- De Sio S, Traversini V, Rinaldo F, et al. Ergonomic risk and preventive measures of musculoskeletal disorders in the dentistry environment: an umbrella review. Peer J. 2018;15:6:e4154.

- Chaffin DB, Andersson GBJ, Martin BJ. Occupational Biomechanics. 4th ed. Wiley; 2006.

- Ortiz HJC. High magnification in dentistry; postural benefits using magnification loupes to improve dental work performance. J Clin Adv Dent. 2023;7(1):13-17.

- Bud M, Jitaru S, Lucaciu O, et al. The advantages of the dental operative microscope in restorative dentistry. Med Pharm Rep. 2021;94(1):22-27.

- Lee J-M, Son K, Kim J-W, et al. Does an ergonomic dentist stool design have a positive impact on musculoskeletal health during intraoral scans and tooth preparation? Int J Prosthodont. 2024;37(6):644-649.

- Bolderman FW, Bos-Huizer JJA, Hoozemans MJM. The effect of arm supports on muscle activity, posture, and discomfort in the neck and shoulder in microscopic dentistry: results of a pilot study. IIE Trans Occup Ergon Hum Factors. 2017;5(2):92-105.

- Moore SM, Torma-Krajewski K, Steiner LJ. Practical demonstrations of ergonomic principles. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. July 2011.

- Katano K, Nakajima K, Saito M, et al. Effects of line of vision on posture, muscle activity and sitting balance during tooth preparation. Int Dent J. 2021;71(5):399-406.

- Rubenowitz S. Survey and intervention of ergonomic problems at the workplace. Int J Ind Ergon. 1997;19(4):271-275.

- Markova VI, Petrova Z, Markov M, Filkova S. Assessing the impact of prolonged sitting and poor posture on lower back pain: a photogrammetric and machine learning approach. Computers. 2024;13(9):1-13.

- Bayar B, Güp AA, Oruk DÖ, et al. Development of the postural habits and awareness scale. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2023;29(2):815-820.

- Schwertner DS, da Silva Oliveira RAN, Swarowsky A, et al. Young people’s low back pain and awareness of postural habits. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2022;35(5):983-992.

- Santos W, Rojas C, Isidoro R, et al. Efficacy of ergonomic interventions on work-related musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2025;14(9):3034.

About the Author

Juan Carlos Ortiz Hugues, DDS, CEAS

Juan Carlos Ortiz Hugues, DDS, CEAS, is a master of the Academy of Microscope Enhanced Dentistry (AMED), associate professional in ergonomics by BCPE, CEAS II, and president of the AMED. He wrote the book, Ergonomics Applied to Dental Practice, available from Quintessence Publishing. He provides lectures, training, and advice on advanced dental ergonomics in Latin America and the United States, mainly related to ergonomics applied to dental microscopy.