Dentistry IS safe for patients!

by Mary Govoni, CDA, RDA, RDH, MBA

It's been several months since a number of dental practices in the U.S. were cited for alleged inappropriate or inadequate infection control practices. As a result of inspections by regulatory agencies, it has been alleged that these practices were not following proper protocol for sterilizing instruments, among other possible violations. While I believe these incidents are isolated and are not common occurrences in the vast majority of dental practices, I am astonished and saddened that the incidents happened at all.

After all the media scrutiny that dentistry received in the early 1990s with the Dr. Acer case in Florida, it surprises me that any dental health-care practitioner would risk the health and safety of patients – not to mention his or her own health and safety and that of the practice's employees.

Did these individuals just not know or understand current infection control guidelines? Were they aware of the guidelines, but did not believe there were risks involved in ignoring them? We probably will never know the answers, but we all experience the effects when patients hesitate to schedule or cancel treatment.

Aside from the health risks to patients and team members, the scariest part of these stories is that people outside of dentistry may form inaccurate opinions about the profession. In my 41 years in dentistry, I've had the privilege of working with and learning from some of the most caring and dedicated dentists, hygienists, and assistants. I do not believe my experiences are unique. Dentistry is a helping profession, not one in which anyone would bring harm to patients – intentionally or not. Having said this, I think now is an opportune time to take a step back and review the facets of instrument sterilization.

Instrument sterilization guidelines for dentistry have been established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The American Dental Association adopted the guidelines as standards of care in 2004. Most state dental boards use the guidelines as standards of care when they evaluate issues regarding patient safety.

The aspects of instrument sterilization discussed in this column are based on these guidelines, which are available from the CDC at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5217a1.htm. I also have a copy available in the resources section of my website at www.marygovoni.com.

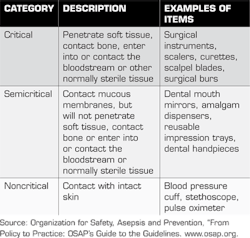

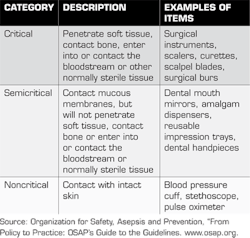

First, let's look at what needs to be sterilized. CDC guidelines state that items need to be sterilized or disinfected after use as patient-care items. These include dental instruments, devices, and equipment. These items are categorized by the "potential risk for infection associated with their intended use."

The categories are critical, semicritical, and noncritical items. The critical items are those with the greatest risk of infection, those that penetrate soft tissue or bone. These items must be heat sterilized. Semicritical items are those with less risk of infection than critical items. They contact mucous membranes and/or nonintact skin. These items should also be heat sterilized if they are heat tolerant. If semicritical items are damaged by heat sterilization, they should be placed in a high-level disinfectant/sterilant (commonly known as "cold sterile"). Items that pose the least risk in infection are classified as noncritical items. They contact only intact skin. A list of common items used in dentistry and their classifications is noted in the table below.

It is important to note that although dental handpieces are listed in the semicritical category, they cannot be processed in liquid chemical sterilants and must be heat sterilized. Slow-speed handpiece attachments, such as prophy angles and contra-angles for burs, should also be heat sterilized.

All items must be cleaned of debris prior to sterilization. This can be accomplished in an ultrasonic cleaner or an instrument washer (not a dishwasher, since they are not FDA-cleared devices). Using enzymatic cleaners in the ultrasonic provides maximum cleaning and removal of blood and other debris.

Products such as Biozyme and Enz-it from Biotrol, Citrizyme from Pascal, EmPower from Kerr TotalCare, Enzymax Earth from Hu-Friedy, Monarch Enzymatic Cleaner from Air Techniques, ProEZ from Certol, and Vigilance Enzyme Ultrasonic Solution from Bosworth are good examples.

The CDC guidelines recommend packaging all instruments prior to sterilization, unless they will be used immediately after removal from the sterilizer. This is to maintain the sterility of the instruments while they are in storage.

Instrument packs, whether pouches or wraps, must be allowed to dry completely in the sterilizer before they are removed. Wet packs or wraps are prone to tearing, and the wet material can pull in contaminants from the air. This can potentially compromise the sterility of the instruments.

For the safety of the team members handling the contaminated instruments prior to sterilization, I recommend the use of cassettes for instrument management. There are many types of cassettes available, from the Steri-Cages and Steri-System Cassettes from DUX Dental, to stainless steel cassettes from Hu-Friedy (IMS), Premier Dental Products, and others.

Dental team members should always consult the manufacturer of a sterilizer to learn how to properly load instrument packs and maintain the sterilizer for optimal performance. Most sterilizer manufacturers, such as A-dec, Midmark, Pelton & Crane, SciCan, and Tuttnauer, have sterilizer manuals available on their websites.

Lack of monitoring of the sterilizer was a major concern in both the Oklahoma and Rhode Island incidents. It was also a factor in the six-month suspension of a dentist's license in Massachusetts about a year ago.

CDC guidelines state that sterilizers should be monitored “at least weekly” with a biological indicator known as a spore test. This testing can be done in-house with systems such as Attest from 3M, ConFirm 10 from Crosstex, and SporeCheck from Hu-Friedy.

There are also numerous outside monitoring services available through dental schools, dental suppliers, and independent companies. This monitoring is a critical validation that each office needs to do to ensure that the sterilizer is functioning properly.

An equally critical step in sterilizing instruments is that of using process integrators in each load or instrument pack. These integrators provide dental team members with validation that each instrument package was exposed to the required parameters for sterilization to occur.

Multi-parameter indicators, which are incorporated into some sterilization pouches -- such as the Sure-Check pouches from Crosstex and integrators, SteamPlus from SPS Medical, and Hu-Friedy Steam Sterilization Integrators -- measure time, temperature, and steam penetration into the instrument cassettes or pouches.

While these integrators are not substitutes for spore testing of the sterilizer, they indicate on each instrument pouch whether the instruments can be safely used. If an instrument pack indicates a failure (lack of color change or indication to reject), the instruments must be repackaged and reprocessed.

One last thing about sterilization. Items that are labeled as disposable are for one-patient use only. They should not be cleaned, sterilized, or disinfected and reused under any circumstances.

I hope that this information will be used by dental teams to review instrument processing. We can always be a little bit more diligent in efforts to assure that dentistry is safe.

Mary Govoni, CDA, RDA, RDH, MBA, is the owner of Mary Govoni & Associates, a consulting company based in Michigan. She is a member of the Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention. She can be contacted at [email protected] or www.marygovoni.com.

Past DE Issues