Group practice: Look before you leap, especially into a nontraditional group (part 1)

Getting into a group practice is easy, but the way out is usually ill-planned, if it’s planned at all. Before joining a group practice, make sure you know your options for both entry and exit.

A traditional group practice usually consists of Dr. Senior and Dr. Junior and maybe two or three dentists or specialists practicing as co-owners. When Dr. Junior achieves ownership, Dr. Junior buys a pro-rata interest in the practice with a mandatory buyout of Dr. Senior, who is often older than Dr. Junior.

While traditional group practices like this continue to flourish, there are now more choices to consider. Forming or joining a group practice for the appropriate reasons is increasingly important in light of other opportunities, which include nontraditional group practices. However, too many dentists and dental specialists form or join group practices for the wrong reasons.

Strategic considerations

Before you commit to a group practice form, determine whether it is the best way to achieve your practice vision. Managing or working in a solo practice is different from practicing in a multiple-owner office, and working in a multilocation practice involves additional complexities that require skills beyond dental or dental specialty training.

Your life can easily become overly complicated due to dentist, dental specialist, and nondentist staffing and training; banking and loan guarantee requirements; systems implementation; and management. The greater the number of locations, the greater the need for administrative managers, who are probably inexperienced in this emerging type of dental practice, although some practice management consultants are now serving as administrators.

Ask yourself these questions: How will the group practice impact your stress level and work hours? Will you lose your autonomy? Is the opportunity for equal ownership (versus minority) available? If so, how much capital must you contribute to become equal, and how long will it take you to break even through increased compensation? If disagreements with the other co-owners become heated, how will you get the practice you contributed back? How much can you contribute to the group practice’s retirement plan? You may have a 401(k) plan, but what about age-weighted profit-sharing contributions, not to mention a defined-benefit or cash-balance plan? You might think you can save outside of your retirement plan, but will you? Probably not.

The need for strategic or long-range planning is crucial, but many dentists do it inadequately or not at all. Getting into a group practice is easy, but the way out is usually ill-planned, if it’s planned at all. If you simply want to practice dentistry or your specialty, reconsider a group practice.

Still want to join a group practice? OK, you had better understand your vision and how to achieve it. But first, let’s examine alternative practice exit and entry choices. (1)

Confirm practice exit and entry choices

A complete sale is simple. The seller gets paid in cash and receives mostly favorable capital gains, and the purchase price is fully deductible to the purchaser. You can hire or become an associate with a complete sale and purchase in one to three years. Thereafter, the seller works for the purchaser’s practice. There is one owner and favorable tax treatment, except for family members with practices formed before August 10, 1993. Solo group arrangements don’t require a mandatory buyout of Dr. Senior. A merger allows an underproducing associate to become busy and can help the seller dispose of an otherwise small, unsalable practice. You can work one to three more years, then close the doors and walk away. The economics are surprisingly favorable. Some specialists will have no other choice.

Criteria for successful group practice

Notwithstanding the necessity of working with honest and committed dentists who are passionate about the profession, there must be sufficient existing or pent-up patient demand. In addition, thorough agreements covering admission, exits, and operations are essential. The agreements are the “rule book” to avoid costly, emotional, and time-consuming litigation.

Preplanning

The practice owner(s) should engage advisors who are experienced in group practice business and tax structures in dentistry. Advisors for the associate should review what has been prepared and paid by the existing practice owner(s).

Advisory team members must interact well with one another. Understand each advisor’s role and how the advisors are paid. Are the lawyer and CPA licensed to practice law and accounting in your state? If not, local counsel and a local CPA should be engaged as part of the advisory team.

Assuming that you have confirmed that you will enter a group practice, authorize preparation of the practice valuation, the associate employment agreement, a letter of understanding for entry, exits, and operations, and preparation of all agreements. When conducting associate interviews, have the candidates sign a confidentiality letter prior to providing any financial, tax, or business information.

If a candidate is not currently working in your practice as an associate, consider using professional advertisements or matching services through professional associations, dental equipment and supply companies, dental schools and residencies, study clubs, and practice brokers. If an associate is currently working in your practice, you do not need to pay a brokerage fee to a practice broker whose primary role is to locate a worthy candidate.

Nontraditional practice groups

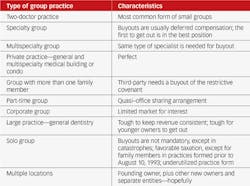

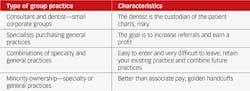

Over the last 20 years or so, dentistry has been undergoing industry consolidation. (2) The basic categories I see are minority ownership, mergers, multilocation offices, nondentist ownership, and investor or corporate practices. Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the forms of group practice that I have encountered and their characteristics.

Minority ownership

Unless talented associates are afforded the opportunity to build equity, share in profits, and maximize compensation and benefits, they will leave for more favorable opportunities. The economics of the purchase must allow for the new owner to earn a living greater than that of an associate and pay for the new owner’s interest within a measured period of time (e.g., not to exceed seven years). The longer the repayment period, the higher the practice value—in which case the practice owner(s) can lose a potential new owner to an alternative opportunity.

From the new owner’s perspective, there are three considerations. First, it’s easy to get in but difficult to get out and receive a return of equity. The buy-sell agreements must be in place for any event that could cause departure. One alternative might be for the new owner to purchase the location where he or she primarily works, pursuant to a predetermined formula. Second, there is a limited market for another dentist to purchase a departing owner’s interest, and the consent of the majority practice owner(s) will be required. Finally, the majority owner(s) will retain the right to sell or merge the practice to whomever the majority owner(s) should determine. If there is a “windfall” to the founder(s) in the practice sale, the agreements should indicate that it be shared with the minority owner(s).

Mergers

It’s becoming more common for specialists to merge their practices together on a state and regional basis. While mergers can be advantageous, they are difficult to unwind without significant and advanced planning. Rather than merging existing practices, I suggest that specialists retain their existing practices and establish or acquire new practices under a new entity. With mergers, the smaller practices are required to contribute capital to the merged entity to establish pro-rata ownership with larger counterparts, and smaller practice owners may never recoup their capital investments. An alternative is to remain separate and form a study club.

Multiple locations

Group practices are establishing multiple locations by purchasing existing or establishing new practices. When a practice is purchased by a group practice, the selling dentist usually becomes employed by the group practice or engaged as an independent contractor, which carries tax risks. (3,4) Also, there is always the possibility that the selling dentist will not meet the expectations of the group practice owners, either clinically or administratively. The group practice should retain the ability to quickly terminate the working relationship of the selling dentist. A challenge for group practices with multiple locations is recruiting and training quality dentists and offering a meaningful future to the new doctors that the group practice desires to retain.

Nondentist ownership

Some states permit nondentist owners, and many do not. (5) In states that do not permit nondentist owners, the nondentist—through an S corporation or limited liability company—renders management services in exchange for fees, owns and leases the equipment to the practice entity, and holds the lease to or owns the real estate. State dental boards seem to focus on the importance of a dentist owning the patient records, rather than profits being channeled to the nondentist(s).

Investor or corporate practices

If the average practice overhead for a general practice is slightly less than 40%, all overhead, including management fees, doctor compensation, and benefits, must be paid. There might not be sufficient profit for investors. Adding to this complexity is the difficulty in managing multiple locations. If the economics don’t work, ultimately the investor and corporate practices will disappear. Time will tell.

Review your choices carefully to decide if group practice, whether traditional or nontraditional, is right for you.

References

1. Prescott WP. Exit choices. Dental Economics website. http://www.dentaleconomics.com/articles/print/volume-105/issue-1/practice/exit-choices.html. Published January 27, 2015. Accessed May 1, 2017.

2. Pride JR, Prescott WP. Who’s the boss? Dental Economics website. http://www.dentaleconomics.com/articles/print/volume-88/issue-3/features/whos-the-boss.html. Published March 1998. Accessed May 1, 2017.

3. Weil D; Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor. Administrator’s Interpretation No. 2015-1. United States Department of Labor website. https://www.dol.gov/whd/workers/Misclassification/AI-2015_1.htm. Published July 15, 2015. Accessed May 1, 2017.

4. Prescott WP, Altieri MP, VanDenHaute KA, Tietz RI. Worker classification issues: Generally and in professional practices. The Practical Tax Lawyer. 2017;31(2): 17-28. http://www.wickenslaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Worker-Classification-Issues-Generally-and-in-Professional-Practices.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2017.

5. Baucus M, Grassley C; Committee on Finance, United States Senate; Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate. Joint staff report on the corporate practice of dentistry in the Medicaid program. American Dental Education Association website. http://www.adea.org/uploadedFiles/ADEA/Content_Conversion_Final/policy_advocacy/Documents/emailDist/Report_on_Corporate_Dentistry.pdf. Published June 2013. Accessed May 1, 2017.

William P. Prescott, Esq., EMBA, of WHP in Avon, Ohio, is a practice transition and tax attorney who was formerly a dental equipment and supply representative. For Mr. Prescott’s publications and course materials, visit PrescottDentalLaw.com. Mr. Prescott can be contacted at (440) 695-8067 or [email protected].