Ask Dr. Christensen

by Gordon J. Christensen, DDS, MSD, PhD

In this monthly feature, Dr. Gordon Christensen addresses the most frequently asked questions from Dental Economics® readers. If you would like to submit a question to Dr. Christensen, please send an e-mail to [email protected].

For more on this topic, go to www.dentaleconomics.com and search using the following key words: sealants, sodium bircarbonate residue, restoration, acid etch, caries, resin, bonding, calculus, phosphoric acid gel, Dr. Gordon J. Christensen.

Q Numerous conflicting articles and courses on sealants have left me completely confused. Are sealants considered to be a responsible therapy? I am hearing that sealants can be placed directly over overt dental caries, and at the same time, I am being told they should not be placed if active carious lesions are present. When and in what situations should sealants be placed? What sealant materials are best? Who should be placing them?A Your multifaceted question is an important one, since millions of sealants are being placed routinely, and you are not alone in your confusion. Everybody seems to have a different opinion on the subject. Frankly, I am tired of the continuing debate over sealants and how to place them. Let's take a logical look at the sealant concept. I will add my own conclusions on sealants, based on my own clinical research and years of observation.Class I dental caries is designated as Class I because this is the site where dental caries is most commonly and first observed. In a nonfluoridated area, Class I caries is frequently diagnosed soon after the teeth erupt. Some estimates say up to one half of the “groovy” teeth have initial caries in them six months after they erupt. This is not the case in fluoridated areas.

What follows are my candid thoughts on sealants. Many of you may not agree with my thoughts. However, these concepts satisfy my own ethical goals relative to this mainly preventive, but also occasionally inadvertent, treatment procedure.

• Along with many others, I contend that dental caries is an infectious disease that should be either prevented or surgically removed. In the 1960s, significant academic research was published, alleging that when caries was “sealed into teeth,” the carious lesions became inert. However, any experienced practitioner who has cut out sealants has found overt, juicy, ongoing caries under the sealants, sometimes leading to pulp exposures.

A frequent rebuttal to the above statement is that sealants with caries under them were placed improperly, and the resin did not “seal” the caries into the tooth. Does sealing the carious lesion in place accomplish any desirable goal? Microbiologists remind us that the organisms involved in dental caries have been shown to be facultative. They adapt easily to both anaerobic and aerobic situations. In my opinion, sealing overt caries into teeth is not an acceptable procedure.

What is involved in proper sealant placement? I will explain my technique later in this column. But, in my opinion, if I see clinical or radiographic dental caries, the patient needs to have the carious lesion surgically excised, followed by the placement of a conventional dental restoration. This is not a situation for placement of a sealant!

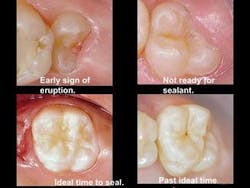

• Ideally, sealants are best placed as soon as the tooth has erupted and the total occlusal surface is clearly accessible. That is usually anytime up to six months after the tooth has penetrated the gingiva (see Figure 1). Placing sealants in the conventional manner later in life — without cutting away tooth structure to see the extent of any potential carious involvement — is questionable, because it is nearly impossible to determine if active caries is present when observing clinically with the DIAGNOdent or with radiographs.

• Sealants should be placed by dental hygienists or dental assistants where legally permissible. A complicating factor is that when the tooth requires cutting with a bur or aluminum oxide, the clinical procedure can no longer be classified as a sealant. It is a restoration requiring tooth-cutting and placement of the restorative material by a dentist. It also requires a higher fee, and it causes families with children needing sealants or restorations to pay an avoidable higher financial burden. The fee for a Class I restoration is about three times more than the fee for a sealant, and the dentist must do the treatment, not the staff person. This is another factor mandating the placement of sealants before six months after tooth eruption.

• The sealant procedure I will describe is a proven success, and does not have to be performed by a dentist. It does not involve tooth-cutting. When the tooth structure is cut by a bur or an aluminum oxide air abrasion, this procedure must be done by a dentist by law. If observable carious lesions are present, I strongly suggest placing a conventional restoration, not a sealant.

The steps for performing a sealant by a staff member are:

1) Clean the tooth. Use an air slurry polisher (Cavitron® Jet Plus™, Prophy-Jet™, or many other brands) on the grooves of the tooth. This sodium bicarbonate slurry removes stain, plaque, and any minimal calculus that may be present. If this is not done, acid used in the sealant technique cannot penetrate into the tooth grooves, plaque remains, and in my opinion, the sealant is doomed to eventual failure beginning on the day it was placed. Stain or calculus on the tooth surface will also provide a false positive reading with the DIAGNOdent. Remove the stain and calculus!

2) Diagnose the tooth for caries. Observe the tooth clinically with a radiograph or a DIAGNOdent. If no overt observable carious lesions are present, continue to step three.

3) Neutralize the sodium bicarbonate residue. Place conventional phosphoric acid gel or liquid into the grooves for a few seconds to neutralize the basic sodium bicarbonate. Wash off the soluble “salt” produced in the acid-base reaction.

4) Acid-etch the tooth. Use your routine acid-etching material, either liquid or gel, to produce a standard acid etch of the grooves. If the grooves are especially deep, tracing them with a sharp explorer will assist in eliminating the bubbles in the grooves. Wash off the acid.

5) Wet the grooves with unfilled liquid resin. Use any unfilled resin to break the surface tension in the groove area. As an example, this liquid can be the last component of any multi-bottle bonding agent, such as the commonly used second component of CLEARFIL™ SE (Kuraray) bond or other brands. After applying this material, blow on the tooth surface to the extent that only a very thin layer of the liquid remains.

6) Place the sealant. For more than 20 years, I have used as my sealant material a very small amount of the same fully-filled restorative resin that I place in a typical Class I or Class II resin restoration. The technique is simple. Place a small amount of the putty restorative resin on the groove area. Place your bonding-agent lubricated fingertip on the resin on the occlusal surface, warm up the resin for a few seconds with your finger, push the resin into the grooves, slide your finger off the tooth to the facial or lingual, observe the bulk of resin to make sure it is not too much, and cure the resin. You have now placed a “sealant” that will last indefinitely! If you prefer to place more flowable conventional sealant materials, do so. However, you should expect the conventional sealant materials to have a shorter service life than standard restorative resins due to lower filler content, less strength, and less adequate wear resistance.

If my comments sound too strong, I apologize. In my opinion, the sealant concept has been abused, overdone, used at inappropriate times, and had remarkable numbers of clinical failures observed by all clinical dentists. It is time to make this useful preventive concept serve as it most assuredly can do, and as it was initially intended to do.

Assuming sealants are placed as I have just described, they are a “win-win” for all concerned — dentists, staff, parents, and patients — because:

- Tooth structure is preserved

- Cost to parents is lower

- The technique is predictable

- Staff persons enjoy the procedure

- The technique is painless

- The “sealant/restoration” serves for a long time

- The practice has a predictable, revenue-producing, appreciated procedure

Having dental hygienists and dental assistants collect diagnostic data makes them a more important part of the team, reduces diagnostic costs, allows more time to be spent in careful exams, and improves staff self-esteem and office revenue.

Our newest video, “Efficient Diagnostic Data Collection by Auxiliaries,” discusses staff becoming highly involved with diagnostic data collection, and it relates closely to the question in this article. Call (800) 223-6569 or visit www.pccdental.com for further information.

Dr. Christensen is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah, and dean of the Scottsdale Center for Dentistry. He is the founder and director of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing-education organization initiated in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is a cofounder (with his wife, Rella) and senior consultant of CLINICIANS REPORT (formerly Clinical Research Associates), which since 1976 has conducted research in all areas of dentistry.