Ask Dr. Christensen

In this monthly feature, Dr. Gordon Christensen addresses the most frequently asked questions from Dental Economics® readers. If you would like to submit a question to Dr. Christensen, please send an e–mail to [email protected].

For more on this topic, go to www.dentaleconomics.com and search using the following key words: resin–based composites, amalgam, resin–modified glass ionomer, RMGI, restoration, pediatric dentistry, Dr. Gordon Christensen.

Q Recently, I had a parent reject the use of amalgam in her 6–year–old child. I have been using amalgam for many years for pediatric restorative dentistry, and I don't see a reason to change. What is the current thinking on use of amalgam in children? Should I change? Are there better materials? Am I out of date because I am still using amalgam restorations?A The controversy surrounding amalgam is not going away in some locations, but our surveys show that at least 60% of U.S. dentists are using amalgam at least some of the time. Amalgam continues to be a relatively easy–to–use material that serves for a period of years without difficulty. However, the alleged health challenges of amalgam continue to be promoted by some health practitioners and many alternative medicine practitioners. Obviously, amalgam does not provide an esthetic restoration. I do not see any major reason to change your use patterns if you do not want to do so, but there are some very good alternatives for the restoration of pediatric teeth. Among the alternatives are resin–based composite, compomer, conventional glass ionomer, and combinations of the named materials. I will discuss these alternatives in this column, with emphasis on my favorite material, resin–modified glass ionomer, for restoration of pediatric (primary) teeth.RESIN–MODIFIED GLASS IONOMER (RMGI)

This material is already the most commonly used one for final cementation of fixed restorations in the U.S. RMGI has proven itself over many years as a luting cement, but many dentists have not accepted it as a restorative material. Why haven't they accepted it? When initially mixed, RMGI materials are sticky and difficult to place into tooth preparations, and the final strength of RMGI is not realized until many hours after placement into tooth preparations. I will discuss methods to reduce these challenges later in this column.

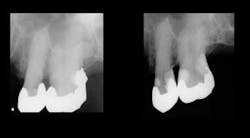

The most popular brands of RMGI restorative material are Ketac™ Nano from 3M ESPE, and FUJI II™ LC and FUJI Filling™ LC from GC (Figures 1 and 2). These materials have been used for restoration of highly caries–active patients such as bulimics, radiation–therapy patients, chemotherapy patients, or those with senile caries (Figures 3 and 4) with notable clinical success. Empirical evidence has convinced me of the cariostatic properties of the RMGI restorative materials.

RMGI is a combination of polyacrylic acid and glass particles. It is the same resin used in resin–based composite, only in a smaller percentage. This combination of ingredients provides the following desirable properties for restoration of pediatric teeth.

RMGI bonds to tooth structure with a natural anatomic chemical bond. The carboxylate ion in the cement bonds to the calcium ion of tooth structure. When subjected to bonding studies, RMGI does not have the high initial bonds reported for resin–based composite. However, when the RMGI bond is analyzed over a long period of time, the bond of RMGI remains strong, while the bond of most resin–based composites degenerates over a period of time.

RMGI releases fluoride over the period of its use in the mouth. Although the effectiveness of this fluoride release comes under some criticism, it has been my clinical experience that new carious lesions are seldom seen around RMGI restorations.

The expansion and contraction of RMGI when subjected to hot and cold foods is minimal when compared to resin–based composite. The clinical significance of this property has been debated over many years, but it appears to be clinically desirable when considered relative to the opening and closing margins caused by temperature changes.

The chemical properties of RMGI provide a phenomenon on tooth structure much like self–etching primers. The mild acid content of RMGI etches the tooth structure, similar to liquid self–etching primers, and the dentinal canals are naturally filled or “plugged” with the constituents of the material. The result is that RMGI does not produce postoperative tooth sensitivity in restorations on an unpredictable basis as do resin–based composites.

On a slightly negative orientation, RMGI does not have the desirable wear characteristics of most resin–based composites. This slightly higher wear characteristic does not bother me when restoring pediatric teeth, since primary teeth are not in the mouth for many years, and the occlusion of a child is in a constant state of movement and stabilization.

Previously, I have noted that RMGI is very sticky when initially mixed. Can this property be overcome? Many dentists begin to use RMGI and find that the material is so sticky that they cannot get it to stay in the tooth preparation. My suggestion is that after mixing the material, do not attempt to place it into the tooth preparation until the material sets to a putty consistency.

How long does the material have to set to have a putty consistency? This depends on the temperature and humidity of the room, the method of mixing, the manufacturers' ratio of powder to liquid, and other factors. The material usually turns to putty in about 45 seconds to one minute. It is very easy to determine when the material will be acceptable for use. It begins to have the consistency of a putty resin–based composite, and it is much easier to control.

You may then place it into the tooth preparation, using an instrument lightly lubricated with either isopropyl alcohol, (wiped onto the instrument with an alcohol–moistened cotton gauze) or a thin layer of unfilled resin–bonding agent on the instrument. Some prefer to load the material into a Centrix or other syringe to place it into the tooth preparation.

The second negative characteristic I previously mentioned is the relatively low strength of RMGI when it is initially cured. This characteristic has discouraged some dentists from using the materials, since they find finishing RMGI difficult. The material can easily be overfinished after it is initially set. How do you overcome this challenge? I suggest the following technique:

- I prefer to use a rubber dam, but you may have other methods that you prefer to produce a dry field.

- Make the tooth preparation.

- Mix the material.

- Let it set to the putty stage.

- Place it into the tooth preparation.

- Cure it with a curing light.

- Isolate the operating area from moisture contamination with cotton rolls or any other method to produce a dry field.

- Come back to the patient in a few minutes.

- Using a dull bur, such as a tapered, pointed, used, and sterilized 7901 trimming and finishing bur for a Class V or a 7406 trimming and finishing bur for a Class II, lightly smooth the external portion of the restoration.

- Use fine finishing disks wherever they will fit.

- Place a layer of glaze, such as BisCover™ LV from Bisco or G–COAT™ from GC America on the surface of the restoration and cure it.

- Tell the patient to avoid aggressive chewing or oral hygiene for a few hours.

The described technique provides a relatively smooth restoration that can easily be smoothed further at a recall appointment in the future if necessary. At a subsequent recall appointment, the material will be markedly harder and more resistant to polishing than on the placement appointment.

What if the primary tooth still has several years to serve the child? When placing the material, you may leave the last 0.5 to 1.0 mm of tooth preparation unfilled with RMGI, and place your favorite resin–based composite as the last thin layer on top of the RMGI.

The result of this technique is that the patient receives all of the positive characteristics of the RMGI as described, but also has the possibility for a smooth, wear–resistant surface on the outside of the restoration.

I hope I have given you an alternative to amalgam for those patients and/or parents who deny the use of amalgam. After years of using this technique, I prefer it to amalgam for pediatric patients. Please also consider the other amalgam alternatives I have listed previously.

One of our recently produced Practical Clinical Courses DVDs for staff, “Rubber Dam — Still the Best Dry Field Technique,” V3522, relates to my answer to this question — how to create a dry field when placing RMGI restorations.

It shows the various ways an assistant can assist the dentist by using dry field methods to best advantage. It includes a step–by–step placement technique for the newest and best rubber dam procedures, plus several other dry field techniques.

One of our PCC courses in Utah includes the hands–on placement of RMGI among many other restorative procedures such as Class II resins, veneers, all–ceramic crowns, and many other topics in esthetic restorative dentistry. The name of the course is “Practical Esthetic Restorative Dentistry.” Call PCC at (800) 223–6569 or visit our Web site at www.pccdental.com for information.

Dr. Christensen is a practicing prosthodontist in Provo, Utah, and dean of the Scottsdale Center for Dentistry. He is the founder and director of Practical Clinical Courses, an international continuing–education organization initiated in 1981 for dental professionals. Dr. Christensen is a cofounder (with his wife, Rella) and senior consultant of CLINICIANS REPORT (formerly Clinical Research Associates), which since 1976 has conducted research in all areas of dentistry.