A menu for routine maxillary implant therapy

by Kenneth W.M. Judy, DDS, FAGD, FACD, FICD

In the October issue of DE, the need for a “unified theory” for mandibular implant therapy was explored. The same need exists for the maxilla and is dependent upon each practitioner's clinical experience. After 40 years of implant therapy practice, the author feels that too often marketing phrases such as “teeth in a day” or “no bone is required” misleads the profession. An important menu item quite often should be “refer to an experienced colleague” whom you trust. Also, the menu for the maxilla is far more extensive when compared to the mandible. Originally, when bone grafting was not utilized as much as it is today, mucosal inserts (Case No.1) or subperiosteal implants (Case No. 2) were utilized to treat the severely resorbed maxilla. Now, the maxilla can virtually be totally replaced with a full-arch iliac crest onlay graft (Case No. 5) or the sinuses can be partially or totally grafted for endosteal implant placement (Case Nos. 3 and 4). Facial bone augmentation is also routine and quite predictable for a single tooth or over a broad area such as the premaxilla. When ideal bone conditions naturally exist, multiple endosteal implants can be placed and immediately loaded, often with computer-generated guides. Small diameter implants are being utilized more frequently for economically challenged patients, but their use in the maxilla should be somewhat guarded and full patient consent should be obtained. In the maxilla, small diameter implants simply do not have as high a success rate as they do in the mandible.

Treatment options (the “menu”)

A high percentage of maxillary cases done in the United States today do involve minor or major bone grafting procedures. The profession was very much misled vis-à-vis the mandible, since many corporate lecturers proclaimed that almost any vertical level of bone could be treated with root form implants and fixed bridges. The maxilla, particularly because of the nature of maxillary bone, is somewhat unforgiving, and if a similar philosophy is adopted, a high failure rate will occur. A well understood “menu” should result both in a high percentage of case acceptance as well as a high rate of clinical success. A series of cases will illustrate the author's personal menu utilized over four decades. All of the general caveats from the October article apply.

Case No. 1: The patient was one of the original patients treated in the United States in the late 1950s by Dr. I. Lew of New York. Dr. Lew placed mucosal inserts in this patient after their introduction by Dr. Gustav Dahl of Sweden. The patient had a gag reflex that did not permit the use of a conventional full or partial denture. A palateless prosthesis retained by mucosal inserts was fabricated instead. The author was privileged to redo the case after the loss of the premolars and because of occlusal wear and ridge resorption. The prosthesis was functioning without incident for well over 30 years. The opposing case was a full denture prosthesis.

Case No. 2: The patient had a circumferential maxillary subperiosteal implant used to treat severe bone loss. Three premolars were retained. A fixed porcelain-fused-to-metal restoration was permanently cemented to three implant posts and into the precision locks on the premolar full-coverage restorations. The opposing arch was natural teeth with posterior fixed bridges. The patient is being maintained by his local general practitioner and is recalled by the author once a year. There have been no problems with the maxillary subperiosteal implant in over 20 years.

Case No. 3: The patient had a unilateral sinus graft, with synthetic materials only, done by the author eight years ago. Three molar implants and an anterior tooth support a six-unit porcelain-to-metal fixed prosthesis. There have been no complications. The patient receives quarterly preventive maintenance appointments only.

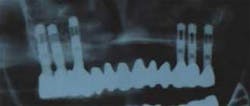

Case No. 4: The patient had a bilateral maxillary sinus graft with iliac crest bone augmented with synthetic materials. Six posterior endosteal implants, placed by the author six months after grafting, support a fixed porcelain-to-metal prosthesis. The grafting was a “refer to an experienced colleague” procedure due to the need for general anesthesia and encompassing a procedure outside of the author's clinical expertise. (Grafting done by Dr. Richard Kraut, Bronx, N.Y.) The only problem that has occurred with the case has been replacement of the prosthesis for the patient's cosmetic requirements. The case has been functioning for eight years.

Case No. 5: The patient had a full arch iliac crest onlay graft totally rebuilding the maxilla. The case fell into the category of “refer to an experienced colleague.” The surgical graft procedure, the prosthetic full denture provisionalization, implant insertion, loading protocol, and fabrication of the final prosthesis were all done elsewhere. (Dr. Carl E. Misch, Birmingham, Mich.) The author has only supervised preventive maintenance procedures for three years. One surgical flap and removal of peri-implant granulation tissue was performed recently. Otherwise, there have been no complications. The opposing arch is a fixed porcelain-fused-to-metal bridge.

With many cases with grafted bone or adequate natural bone where only a limited number of implants can be placed, an overdenture prosthesis is recommended. The implants can be splinted or free standing. The duration of treatment, costs, and requisite skills needed are broadly described based on the author's experience (see chart).

Conclusion

Clearly, for each procedure on this “menu” there is a need for substantial education, understanding, and experience. The author has attempted to show a spectrum of treatment options based on existing conditions when patients first present or on those that can be created. A balance between patients' functional needs and financial capabilities has to be individually resolved. Implant therapy has also been shown to be a dynamic, ever-changing field of endeavor.

Dr. Kenneth Judy is co-chair of the International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI). He is clinical professor in implant dentistry at New York University College of Dentistry, as well as in oral implantology at Temple University School of Dentistry. He has been involved in implant research and practice for more than 40 years.