You Can’t Paint a Picture Without a Brush (Part 2 of 3)

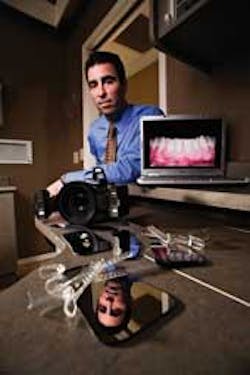

by Glenn D. Krieger, DDS, FAGD

My last article covered the basics of why all dentists should consider incorporating high-quality digital clinical photography into their practices. It’s easy to understand how this technology can quickly and easily transform a practice into one that treats patients more comprehensively, while creating a partnership with patients as they undergo care. It truly is a no-brainer for those who want to see their practices grow in an ethical way, without having to see a massive stream of new patients every month. By using today’s digital technology, one can better document cases for comprehensive diagnosis while watching case acceptance go through the roof.

It doesn’t happen by accident, so it’s important to understand some of the steps, techniques, and tools necessary to take an average practice and convert it to one with informed patients who readily say yes to treatment. My goal in this article is to focus primarily on the physical tools needed to help dentists capture and present incredible images with as little effort as possible.

If one wants exceptional images that draw patients in and help them make tough decisions about treatment choices, the images must be well composed and properly lit. This sounds easy enough. Just get it in focus and use the attached flash, right? Well, not exactly. If you keep in mind my favorite phrase “Good is the enemy of great,” you’ll appreciate that the tiny amount of extra effort necessary to capture amazing images is worth it. When compared to merely adequate images, you’ll wonder how anyone could settle for anything less.

Any dentist who wants to start with this approach will need to invest in some basic tools to help make the process from diagnosis to presentation easy. Yes, it will cost money, but in my 15 years of practice I cannot think of any other investment that has had as quick and as large a return on investment as my camera, mirrors, retractors, digital software, and attendance at a hands-on course. Aside from the tremendous changes in my patients’ oral health, I presented and watched them accept so much new treatment that my entire investment was paid off with the first case I presented using the digital co-diagnostic approach. Within four days (yes, four days) of starting this digital imaging workflow, I had two patients say yes to treatment worth more than $40,000. It’s not about the money for me, but it certainly doesn’t hurt that there’s a nice return on investment when helping patients with occlusal breakdown or functional issues.

In order to use these techniques, the first thing to purchase is a high-quality digital camera. I touched upon this issue in my last article and will discuss it here. I’ll reaffirm my position that the camera type most suitable for capturing exceptional images is a single lens reflex (SLR) camera. There are, of course, point-and-shoot cameras being sold as dental cameras, but to me it’s analogous to using the family car in a NASCAR race. No matter how you modify it, it will never be able to compete with equipment specifically designed for the suited purpose. Once one learns how to easily use an SLR camera with adjustable flash and aperture settings, the limitations of point-and-shoot cameras become readily apparent.

For clinical photography, digital SLR cameras are perfect for up close, deep focus, well-lit images. The lens of choice for such photography is generally a 105 mm macro lens. The term macro means that one can get very close to the subject and still be in focus without any special modifications to the lens. It’s as simple as composing and focusing on the image. When showing a single molar to a patient, and that single tooth takes up the entire frame, be no farther than six inches from the patient. This is where SLR really shines. The lenses and external flash systems are ideally suited for this type of work.

A variety of camera manufacturers make great SLR cameras with appropriate lenses, and each has benefits and limitations. Companies that have found a strong place in the dental SLR market are Canon, Nikon, and Fuji. I believe that it’s important for every dentist to figure out which camera system fits him or her best.

Most reasonable dentists would never consider asking a supply rep what type of drill they should buy and merely accept their suggestion and purchase it. Likewise, don’t just walk into a camera store or dental photographic company and take their word on the camera you should buy. It is vital that every dentist receive training at a hands-on clinical course that provides loaner cameras before making the investment in a camera for office use. By far the biggest problems I see at my hands-on courses are dentists who have been sold on a particular camera before learning how to properly use it. Once these dentists use my demo cameras, they often determine that the camera they bought isn’t right for what they are trying to do.

When looking into camera systems, a buyer must determine the number of megapixels. Before deciding, let’s define what a pixel is so we may better understand what image size really means to camera use in the clinical setting.

If you’re an art fan and appreciate the style “pointillism,” you’ll understand that this painting method is characterized by the use of paint dots to create images that, when viewed from a distance, make the individual dots disappear and blend to form a comprehensive image.

A digital image is no different than pointillism. Significantly magnified, your digital images will appear to be a bunch of dots, or pixels. These dots, when viewed from an appropriate magnification, make up your well-composed image. A 10 megapixel image means that the image is made up of 10 million pixels. The more pixels the camera shoots, the more dots make up the image and the finer the detail. However, keep in mind that the best monitors most of us will currently use in practice are 1,600 pixels wide by 1,200 pixels down. Multiplying those two parameters equates to a screen that will show roughly 1.92 million pixels. On that screen, a 2 megapixel image will look as good as a 10 megapixel image because the screen can only show 1.92 megapixels.

When printing images, the amount of pixels plays a large role, as does cropping and magnifying images on screen. However, the point that I’m trying to make is that when looking into a camera system, don’t get hung up on the differences between 8 and 10 megapixel cameras. The difference to clinicians will be so small that choosing a camera solely for the size of the image it produces is a mistake. Other factors should play a bigger role in selecting a camera.

I’m often asked whether all camera systems see color the same way. Although no camera will give 100 percent color accuracy without using other tools and techniques, some camera systems are clearly closer to natural color than others. Look at all camera systems and figure out which one has the color that best suits you.

Other things to look for when choosing a camera are ease of use, available flash systems and lenses, display screen size, and simplicity of menu navigation, to name a few. There are lots of options and choices, and consulting an educated source is always a good idea before buying a camera system.

Once you’ve chosen your camera, flash, and lens, the next step is to purchase quality mirrors and retractors. Once again, there are many options and you’ll need to determine which set is best for you. This is certainly an area where I have my own biases.

In my opinion, rhodium-coated, handle-free mirrors are the best available option for high-quality images. Most of them are double-sided and give exquisite, distortion-free reproduction of the image. They are a bit more expensive, but well worth the small price difference when compared to other materials such as stainless steel. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes for buccal, occlusal, and lingual shots, or anything else you may think of. I suggest that when buying mirrors, consider getting two of each size you plan on using so if one is damaged, a backup is available. It’s also nice to have an extra set in case several patients need images taken on the same day. The staff won’t have to rush around and drop what they’re doing to sterilize the only set of mirrors in the office.

Students at my lectures or hands-on workshops often ask me about retractors. Although I was trained a dozen years ago with the standard stainless steel retractors, I’ve since switched to plastic. In side-by-side comparisons between plastic and metal retractors, I’ve found plastic retractors to be superior for retraction of the lips and cheeks, particularly in the anterior region. In addition, plastic retractors can be modified with a diamond disc or acrylic bur so that they are better suited for a variety of image types. Plastic retractors are generally inexpensive, easily sterilized, and best of all appear almost invisible if they accidentally find their way into an image.

With the discussion of the armamentarium necessary for capturing images complete, let’s talk about the equipment and software for our “digital darkroom.” We’ll need to upload and store the images as well as edit and present them.

In my next article I will offer a broad overview of the workflow process for image management and presentation. For now, I’d like to touch upon the fact that in my practice, I keep all of the images on the computer in my consultation room. There are many reasons I do not view them through the patient’s chart in my practice software, but for brevity’s sake, let me offer a couple of quick reasons why I do it this way.

I like the fact that by not directly importing and managing them in my practice software I can easily copy, export, and manage the images using any outside software designed to work with this type of images. I have often found practice software to be a “roach motel” where the images go in, but never seem to be able to come back out. Additionally, I use images primarily to diagnose and present treatment options. This is always done in my consultation room and rarely with the practice-management software as an aid. If I ever need an image and the patient’s electronic chart at the same time, I just jump back and forth between the two by clicking on the task bar. Last but not least, the network can be set up so that the consult room images can be easily accessed anywhere in the office and displayed on any screen at any time. I crave simplicity, and the idea of using simple software to save my images has appealed to me for years.

There are many systems for saving images on your computer, and most are simple and inexpensive or free. Personal preference is the key. There are a variety of courses and workshops that can teach you how to find the system that works for you.

The final items necessary for implementation of the digital co-diagnostic workflow are image editing and presentation software. Although there is a variety of programs available, two in particular have set themselves apart due to their powerful options and ease of use. For image editing, the choice is Adobe Photoshop, and for presentation, Microsoft PowerPoint.

Adobe Photoshop has two basic versions - the complete suite or Elements. For most dentists getting started with image editing, Elements allows all of the basic functions necessary for cropping, rotating, and sharpening images to present them to patients. If it’s advanced functionality one wants, however, the complete version of Photoshop is a better choice.

Keep in mind that although one can often find bargains on the complete version (particularly if one teaches at an academic institution and has the ability to buy it at a university bookstore), the cost difference between the Elements and full version can be as much as $700.

Microsoft PowerPoint can be purchased singly or as part of the Microsoft Office Suite, where it comes bundled with other programs such as Word and Excel. The program is essentially the same no matter how you purchase it. The main function of PowerPoint is to allow images to be presented to patients in a seamless, easy-to-view show that can be easily created in a few minutes once the user has been properly trained.

While PowerPoint is relatively easy to learn, Photoshop can be quite intimidating. Although Adobe created Photoshop to help graphic artists and professional photographers work with images, we can adapt it easily for dental use. It’s my feeling that anyone who wants to learn Adobe Photoshop for dental imaging should learn from someone who specifically teaches dental applications of the program. As I’ve studied the program and consulted numerous Photoshop experts, most simply focus on the functionality of Photoshop and don’t realize how dentists can efficiently use this program for patient education and case presentation. It’s important to remember that because of the incredible power and functionality of Photoshop, there are often several ways to accomplish a given task. Being tutored by a “wet fingered” dentist will jump-start the learning curve as compared to attending a Photoshop course at a community college or camera store.

Sure, one needs to buy a camera, lens, flash, mirrors, retractors, software, and proper training to get started with capturing, editing, and presenting exquisite images. However, don’t let the upfront costs associated with purchasing the proper equipment and attending a good hands-on clinical workshop stop you from embarking on this amazing journey. Dentists who want to improve their diagnostic skills and case acceptance by using the digital co-diagnostic workflow will be quickly rewarded with a tremendous return on investment and a sense that they are truly making a difference in their patients’ lives.Glenn Krieger, DDS, FAGD, is the director of the Continuum for Complete Care, which provides hands-on courses to teach dentists and staff how to use high-quality clinical photography as a diagnostic tool for comprehensive treatment planning and practice growth. Dr. Krieger also lectures on clinical photography and “Digital Co-Diagnosis” as treatment planning tools. He practices in Seattle, Wash., with an emphasis on comprehensive treatment. For more information on his lecturing or courses, visit www.betterdentalimages.com. Dr. Krieger can be reached at [email protected]. His blog address is http://dentalphotography.blogspot.com.