Part 10 — Outcomes-based practice ...Revealing deep structure through factor search

by David W. Chambers, EdM, MBA, PhD

Dental manufacturers think in terms of components. Researchers and educators think in terms of factors. Practitioners have to be bilingual.

My last two articles presented the techniques of outcomes-based dentistry using components. A component is a self-contained package of characteristics, such as a dental material, a brand of curing light, an associate or other staff member, a reimbursement plan, or an X-ray unit. The component is something physical, and component switching means changing the whole component, not changing parts of it. At its most elemental level, dentistry is a set of components organized into procedures.

There is an approach to analysis, however, that goes deeper than components. Buildup materials for crowns have brand names because they are components. They also have characteristics, such as setting time, marginal integrity, ease of use, sheer straighten, and cost. The characteristics that comprise components are called factors. Alternative components may overlap considerably in their factors, and much of component search and component switching is just a convenient way to get to prepackaged factors.

Dental manufacturers think in terms of components. Researchers and educators think in terms of factors. Practitioners have to be bilingual.

In this article, we will discuss a basic technique for factor search. In the next installment, we will look at factor switching. The factor-search technique is extremely powerful, because it reveals the underlying characteristics that promote success and failure in a practice without requiring the practice to modify treatments or engage in experiments. The searching is done under naturally occurring circumstances.

To illustrate factor search — sometimes called the paired comparison technique — consider an endodontic specialist (or an office performing a large number of endodontic procedures) who is interested in isolating factors underlying therapeutic success. It is not necessary to use numerical measurements in factor search. The only requirement is the ability to distinguish the better result from the worse result among pairs of procedures.

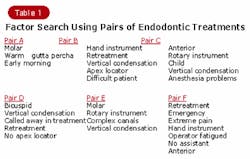

Take a look at the data in Table 1. Six endodontic procedures are randomly paired — Pair A through Pair F. One or more dentists and staff members examine the records and notes concerning each of the 12 treatments. What the evaluators are looking for are differences between the pairs. They record only the factors that are different in each case.

Let's assume in Pair A that both the best and worst procedures were hand-instrumented. Because this is not a difference between the pairs, the technique used is not recorded. Similarly, let's assume that neither of the procedures was performed on a child. Again, there is no difference, so nothing is recorded. One of the procedures was performed on an incisor and the other on a molar. This is a difference, and, for the sake of this example, we will assume that the worst result was associated with the molar; therefore, the factor value "molar" is recorded. Another noted difference involves the filling material — the poorer result occurred using warm gutta percha. Another difference noted is the time of day the procedure was performed. It happened that the best procedure was done in the afternoon and the worst procedure in the morning. (In this example, we are recording the factor associated with the worst result. Alternatively, we could choose to record factors for the best, but we must be consistent.)

When the differences between the best and worst procedure in the first pair are exhausted, the second pair is considered in a similar fashion. For our example, differences in the procedure associated with the worst result in a second pair include hand instrumentation (as opposed to rotary instrumentation), retreatment (as opposed to initial treatment), vertical condensation, the use of an apex locator, and a particularly uncooperative patient. This process of finding differences can be repeated for additional pairs of results, six to 12 normally being a convenient number. It bears repeating that such comparisons are easy to conduct, because they involve naturally occurring events in the office.

The final step in variable search is to lay out the lists of differences side by side and look for common features. It appears that tooth morphology is not a factor that affects treatment success in this case, since molars, bicuspids, and anterior teeth all showed up on the list of worst results. Similarly, the use of an apex locator does not appear to be a critical factor. It does appear, however, that vertical-condensation technique is a factor that must be explored in distinguishing success and failure in this practice. It figured in four of the six worst cases. Disruption in the treatment routine also appears to be worth studying.

Factor search is an easy procedure to use. It involves no mathematical calculations, but it is highly dependent on the ingenuity and integrity of the dentist — or, better yet, on the group of individuals comparing the results. It is a perfect exercise for study clubs. There is also some judgment involved in interpreting the findings. In this case, it appears that vertical condensation is a factor that differentiates success from failure. This does not mean that vertical condensation is an indefensible technique. What it does mean is that this office, this operator, this method for delivering vertical condensation is ineffective. Perhaps it is simply a matter of a valuable procedure being delivered with the wrong technique.

This illustrates an important difference between outcomes-based practice and evidence-based dentistry. Researchers use the results of experiments to draw conclusions about techniques or materials in the abstract — i.e., vertical condensation is good or bad. Knowing about the techniques in the abstract, however, does not tell anyone how it will perform in the office. A valid technique improperly performed cannot be defended based on the literature. Practitioners must use the results of their own experiments to build better practices in the particular.

Another important difference between research and continuous practice improvement concerns the use made of insignificant findings. In the example we are considering, there was no difference in results when using rotary instruments or apex finders. In the research context, "no difference" normally means no publication and no useful information generated. In practice, locating factors that make no difference is a tremendous advantage. If consistent comparison between two dental materials shows no difference in outcomes, go with the material that gives the greatest speed, the greatest ease of use, and the lowest price.

One use of "no difference" in the factor-search technique is to reveal hidden problems. When materials or methods that are assumed to be different produce no differences in practice, this is a signal that the correct operating procedures are not being followed, case selection is being violated, the shelf life of the material has expired, etc.