Communication skills for successful relationships

Chapter 6 — Asking for forgiveness

by Sandy Roth

The instructor's name was long forgotten, but his admonition rang clearly in Dr. Hanley's brain: "There are two things a dentist should never say: 'Oops!' and 'I'm sorry.'" Dental school was a distant memory, yet his warning had stuck with her, and she had taken it to heart on many occasions.

This day had been one for the record books. On two occasions — with patients and with staff — Dr. Hanley had been on the verge of blurting out what was on her mind. She held back, however, mindful of the warning from so many years earlier.

Her patient Phyllis' bridge was the first event. Had an evil spell been cast on those four teeth? First, the lab lost the impression, so Phyllis had to be rescheduled for another. Then, at the try-in appointment, the porcelain chipped off at the margin. On the third try, the shade was off — just slightly, but enough to completely exasperate an already annoyed Phyllis. Three months went by before the case was finally completed, complicated by holidays, vacations, and Dr. Hanley's full schedule. Although the final seating went like a dream, it hardly made up for the nightmare preceding it. Dr. Hanley wasn't sure who was most relieved to have it over — she or Phyllis. Her inclination had been to say, "I'm sorry this didn't go well for us," but she feared the implication of such a statement. So she remained silent.

Then, a letter arrived from another patient, Jim Covington, who was leaving the practice because the hygienist had, in his words, "... treated me like a child, talked down to me, and scolded me ...." Jim was definitely not a troublemaker and he was probably reflecting the events accurately. Dr. Hanley knew she would ponder her response for a while. Patient complaints caused her enormous distress. She realized, looking back, that she had developed a pattern of ignoring them until it was too late. The chart would be inactivated in a few days, and the problem would go away. Or would it?

The staff issues were a different story. Dr. Hanley addressed them, but not well. Jamie, the hygienist, had been inexperienced when she was hired. The practice had been so busy and short-handed that there hadn't been time for formal training.

Still, she was annoyed that Jamie hadn't caught on more quickly; the errors were increasing. In an unguarded moment, Dr. Hanley had vented to her assistants. Jamie overheard the worst of her thoughtless comments and left the building crying. Dr. Hanley was clueless about what to do. She wanted to call and apologize, but when they finally spoke — Jamie initiated the call to tender her resignation — all Dr. Hanley could get out was defensiveness and blame.

Dentists and staff members can easily find themselves stuck in relationships that don't work: employers and employees who don't click; coworkers who are constantly at odds with one another; teams that groan at the sight of a particular patient's name on the daysheet. How did these relationships get into such a mess?

Each relationship begins with a clean slate — no pluses, but no minuses either. At some point something undesirable happens: a team member fails to live up to the dentist's expectations; one coworker steps another's toes; the patient makes an unreasonable demand. These events aren't significant enough to throw a relationship into permanent jeopardy. Serious problems are more often triggered by the response — or lack thereof — to the event.

People often dodge uncomfortable situations by avoiding the issues. As honest as most people believe themselves to be, they are often just the opposite. Sometimes people simply tell an untruth. But in most cases, they lie to avoid a confrontation.

No one enjoys conflict. Yet conflict is paradoxical: you get what you most fear. Those who fear and avoid conflict tend to have more of it; insignificant issues go unaddressed and grow into major battles. Avoiding them means lying. Failing to address an issue in which you have an interest is dishonesty by omission. Thus, avoidance is a major factor in failing relationships.

In each of Dr. Hanley's situations, the responses lacked up-front honesty. And while I can understand from a legal standpoint why we sometimes avoid apologizing, relationships suffer when people are unable or unwilling to express feelings of regret if not actual responsibility.

So, when your wife asks whether a certain article of clothing makes her look fat, do you tell her it does? Would avoidance be so terrible? Situations like this call for diplomacy and tact rather than dishonesty. "I like the green pants much better," is an answer that addresses the issue honestly minus any brutal reference to a sensitive area.

In many dental practices, however, these situations are seldom so easily resolved. We more often must either speak the truth or step aside. In this sixth installment of "Communications Skills for Successful Relationships," I'm going to turn your attention to how to ask forgiveness as an entry point to cleaning up a messy relationship. No one is blameless when a relationship deteriorates. Each party bears a responsibility in the series of events that lead to a relationship breakdown. Acknowledging this is the first step.

Accepting your own complicity is extremely difficult when you are angry at the other person; assigning blame or acting judgmental is normal. Although blame might make you feel stronger by justifying your anger, it only makes things worse. Let's face it: In the midst of a conflict, no one will ever say to you, "You know, you're absolutely right! I am totally wrong, and you are guiltless. Thanks for bringing that to my attention!"

By the time serious conflict erupts, both parties are behaving defensively: comparing notes with others; building alliances; gathering evidence. "You did this and you are wrong" is followed by "Oh, yeah, well, you did something else, and you are more wrong!" Each person becomes more solidly rooted in the rightness of his or her perspective.

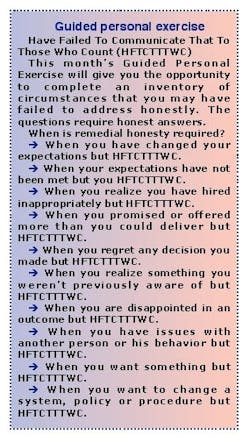

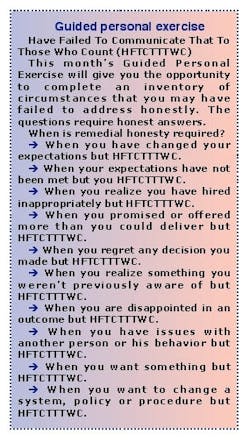

Resolving a bad situation requires someone to apologize; it might as well be you. If you were initially dishonest, correct it with remedial honesty. Remedial honesty requires us to acknowledge the omission, the impact, and the part played in allowing a situation to deteriorate. It begins with an apology for avoiding or ignoring an issue or for failing to be clear. You must identify the part you played, acknowledge it, and express regret for the implications.

Some people call this "eating crow"; I call it taking the higher road. As you begin to clean up relationships, you will learn how good it feels to say, "Please forgive me. I know if I'd spoken up sooner, things would be better between us right now. I hope things improve from the conversation I'd like to have with you now." Or to acknowledge a more insidious role by saying, "I want to begin by apologizing for having several conversations with other staff members prior to this one with you. I suspect I may have greatly contributed to the negativity you are experiencing with others, and I regret handling it that way. I hope you will accept my apology before we begin talking about the specific issues I have."

Once you've apologized for not being completely honest sooner, you will have a better opportunity to address the issues and rebuild the relationship. Here are several suggestions to guide you in remedial honesty.

You must honestly represent yourself. It is always appropriate to represent your feelings, wants, concerns, fears, aspirations, standards, and expectations. But you must represent all of them. If you have been reluctant, say so and why. If you have been fearful, identify your fears. If you have been embarrassed by your own behavior, acknowledge that as well. Take responsibility for your role. In representing your perspective, you must accept responsibility for the part you played before asking your partner to look at himself. This is the price of the ticket and you must pay the toll. Motive is key. When honestly expressing yourself, the motive is always more important than the words. If your intent is to hurt another person, you will — no matter how nice your words sound. And your comments can be hurtful even when your intentions are not. The other party may feel bad about the truths you express, but those feelings will come from the content of your message, not from your intention. Sincerity is important. Don't "shine" others on. Going through the motions of apologizing without sincerity is insulting; don't say anything that you don't legitimately feel.After checking your motive, the skills, style, sensitivity, timing, words, and environment you choose can contribute either positively or negatively to how well your message is received. Make sure you do everything possible to help the other party understand your intentions. Speak privately, if appropriate. Open yourself to questions from the beginning.

Making yourself vulnerable will permit the other party to be vulnerable as well. Choose a time that allows a full discussion without interruptions.

Check it out. Remedial honesty is largely a process of checking things out. Remember that you rarely see the entire situation from your limited perspective. Once you express your perception, be prepared to hear a response that modifies the "truth" as you thought you knew it. You must be a model of maturity and patience; listen thoroughly and respond without defensiveness. Vocabulary. A full vocabulary will help you express yourself precisely. In my days as a Philadelphia police officer, I learned that many people in trouble with the law lack resources — not just money, but also communication skills, including the ability to articulate thoughts and feelings. When people lack the ability to express themselves adequately, issues are more likely to spiral out of control. Consider it a thankful part of your job to master an effective vocabulary. Round words. When a word comes out of your mouth it can be either sharp or round. Sharp words don't feel good when they come out and sound harsh to the ear. Choose round words. "It seems to me that ." beats "Oh, yeah? Well you ..." Or, "Help me understand what you were thinking when ..." is more effective than "Why did you do that?"Replace words that accuse or blame with those that don't carry such an emotional load. Work at developing the ability to find round words first.

Apologize again if necessary. The first thing that comes out of your mouth isn't always what you intended. If you hear words and wish you could take them back, do it! Set your ego aside and apologize for the misstep if necessary.

"That didn't sound like what I meant to say. Please forgive my unfortunate choice of words. Let me try that again." This is an important step when you realize you have added unnecessary fuel to the fire.

Saying you're sorry and asking for forgiveness isn't the hardest thing in the world. But not asking for forgiveness might be under certain circumstances. I hope you will consider how asking for forgiveness might open lines of communication and begin the process of rebuilding failing relationships. I encourage you to try it. I suspect you will feel better and be happier for the effort.

To learn more about how you and your team can develop stronger and more effective communication skills, call Sandy Roth at (800) 848-8326 or send her an e-mail at [email protected] to request a catalog of learning resources.