Clinical COACHING

Applying a tried and true concept to dentistry

by Michael E. Hrankowski, DDS

You signed up for the course six months ago, borrowing valuable time from your practice schedule to attend. The lecturer has a fabulous reputation, which you learn is well-deserved. At the end of the day, you're convinced the seminar was definitely worth your time. The information was well presented; the slides were clear and highly illustrative. No question — this is a clinical idea you want to integrate into your practice, and you can't wait to get started. But what typically happens on Monday morning? All too often, the learning fails to take hold. Who hasn't experienced attending a course and getting all fired up about a new technique, only to struggle with implementation? We buy the materials and equipment and ... nothing. The excitement wanes and the purchases get relegated to a back shelf. We've expended time and money with zero return.

It's not because there is something wrong with the ideas, the lecturer, or us. Classroom courses predictably fail to improve skills because the learning is not experiential. Researchers and professional educators know that skills aren't developed intellectually; they require ongoing integrating experiences to become internalized and mastered. For this reason, new information acquired at lecture courses is difficult to put into clinical practice; dentists get frustrated when the results don't seem to be worth the prices. In addition, the lecture approach isn't very effective when the staff is not involved in the learning. Solo dentists will be faced with the chores of both teaching the staff and convincing them to implement the change. Unless they see the benefit of these efforts, often there is resistance.

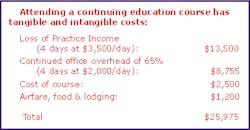

Many study clubs, learning institutions, and associations offer hands-on workshops. Although these can be highly beneficial learning experiences when the staff is involved, the cost of such ventures is generally quite high. Tuition, airfare, hotel, meals, and lost production can easily mount up. And the knowledge acquired through these venues doesn't always make it back to the office.

How can we change this course? How can a dentist with a busy practice and little time for continuing education successfully acquire and implement new techniques in a cost-effective manner? Equally important, how can this newly acquired knowledge get successfully translated into better patient care and increased revenues?

The answer lies in an old concept that somehow never made it to clinical dentistry: coaching. An ice skater with dreams of Olympic gold doesn't take a two-day course and return a champion. Neither does an aspiring concert pianist listen to an eight-hour lecture and instantaneously make it to Carnegie Hall.

While the majority of dentists are solo practitioners, other professionals like medical and surgical residents work directly with their mentors to become proficient in their diagnostic, clinical, and people skills. Apprentices in many other fields have worked under the tutelage of masters and, having developed mastery, gone on to become mentors to others. Your children likely have sports coaches or work with coaches in music or art. You may take golf lessons and perhaps even work with a management consultant. So what about your clinical skills? Perhaps it's time for a paradigm shift.

Clinical coaching can have many benefits over traditional forms of continuing education. Consider the following practice:

The dentist has been practicing for 12 years and has grown quite busy. She has been practicing much the same as she was taught in dental school. The hygienist sees new patients for a cleaning and four bitewing films. The dentist then comes in and performs a brief exam, diagnosing "on the fly" and recommending treatment for only the worst tooth.

More often than not, amalgams are the recommended treatment. She knows that a gold or ceramic onlay really would be a better restoration, but she's not sure how to present the treatment, and she is a little unsure of her skills. This dentist knows she needs to pursue additional learning and has identified the following goals:

- Learn a more comprehensive approach to care and integrate occlusal therapy into practice.

- Decrease the number of crown and bridge remakes.

- Learn a more effective case-presentation technique.

- Move from single-tooth amalgam fillings to quadrant composite or bonded ceramic restorations

The perfect choice to achieve these goals: a clinical coach. Here's how it might work:

Step one:Telephone consultationThe dentist and the clinical coach meet over the phone and discuss any relevant issues. Basic practice description, the current situation, the dentist's goals, a review of the staff, and other topics are part of the conversation. If the dentist and the coach agree they have a basis for working together, a detailed questionnaire is sent to and filled out by the dentist.Step two:Preliminary treatment planThe coach prepares an initial outline of how the in-office time might be structured. Included in this "treatment plan" would be the number of coaching sessions, the objectives of each session, and the coach's fee. The dentist reviews the plan and either accepts or modifies it as required.Step three:Coaching sessionsThe clinical coach's prime objective is to help dentists achieve their stated goals by offering in-office, hands-on, live coaching instruction and training. The coaching sessions are a mixture of over-the-shoulder guidance, demonstration, evaluation, theory, and discussion. Other resources such as computer slide presentations and videotaping may be added as needed. Based on the dentist's needs, the coach will suggest an appropriate mix of clinical procedures to be scheduled during each coaching session. The schedule must allow sufficient time between each session for the dentist to practice the newly learned skills and to identify roadblocks to implementation. The coach also will spend time coaching the staff, as the team's support of the process is vital to a successful result.Dentists who are considering hiring a clinical coach have many of the same questions. The two main questions that arise are: "How will my patients respond to an outsider giving me instruction?" and "How will my staff respond?"

The answer to both questions is: "Overwhelmingly positive!" Patients and staff alike usually feel honored to participate. Most patients express appreciation for the extra attention and report increased confidence in their dentists for taking these extra steps to provide quality, comprehensive care. Dental staffs also welcome a chance to actively participate in practice-improvement measures; with their input valued so highly, there is less likelihood of "feet-dragging" and sabotage.

Another question that comes up is: "Do I charge my patients for their participation in a coaching session?" The answer is generally yes. One of the major advantages of this approach to continuing education is that the dentist continues to see patients and collect fees. Some dentists, however, choose to reduce their fees by a token percentage as a gesture of appreciation for their patient's participation. I have even heard of some dentists actually charging their patients more for this added value. Of course, these issues should be handled individually and discussed with the coach and the patient beforehand.

Naturally, there are always questions of cost. Practitioners base the fees upon the number and type of sessions and the dentist's individual goals. Surprisingly, a series of coaching sessions is significantly less than what a corresponding week away from the practice would cost. Also, there is measurable monetary success when the techniques are fully implemented, resulting in substantial added value to the practice and patients alike.

Besides the monetary factors, consider the value of having a trusted relationship with a mentor and coach. No longer "in it alone," the solo practitioner will have meaningful support in the developmental process. The dentist also will feel a real sense of accomplishment in learning and mastering new skills. And there will be a renewed enjoyment to practicing at a higher level. There's also the esteem factor. Patients will talk to others and staff will laud their dentist's efforts at improving the quality of care and the position of the practice in the community.

Coaching is an idea whose time has come to dentistry. With multiple and obvious advantages, it is hard to imagine who could not benefit personally and professionally from a coaching relationship.