Making the most of your money — Step 4 — Investment planning: making your dreams come true

by Hugh F. Doherty, DDS, CFP

One of Wall Street's most important strategies, asset allocation, is suffering an untimely demise. Several years ago, few doubted the virtues of reducing risk by spreading stock-market bets widely. But today, there is ample evidence that investors aren't bothering with diversification (asset allocation). Mutual-fund companies are rolling out "focus" funds that stick with just a few dozen stocks. Most worrisome is the fact that investors seem to view buying anything other than U.S. blue-chip stocks as increasingly foolhardy. According to Lipper Analytical Services, fund researchers, less than 16 percent of stock-fund assets are in funds that invest with broad diversification.

What is going on?

I believe that it is a potentially disastrous case of rear-view-mirror investing. If you look at performance since 1990, it's easy to trash diversification; United States large-cap stocks have done so well that people don't feel they need to own anything else. We are currently seeing signs that this fantastic run won't last forever. When it ends, international stocks and small stocks could provide a cushion. Make no mistake — stock-market diversification isn't a cure-all. A well-diversified portfolio can still go down. But the ups and downs are more gentle.

The basic idea of diversification is to combine a host of different companies, large and small, domestic and foreign. When some sectors and stocks are suffering, others will do well, giving your portfolio a smoother performance and ensuring that your wealth isn't badly damaged by a few rotten investments.

In my experience, when formulating an investment strategy, it is important to have broad diversification by asset class and style to manage risk and provide above-average, after-tax returns. Your time horizon when investing in stocks should be for a decade or more. Diversification can mean the difference between making decent money and failing to meet your investment goals. To diversify means that you do not put all of your assets in any one type of investment. Similarly, it is not wise to invest only in the shares of any one company or industry. Clearly, you will reduce investment risk with diversification, because bear markets and business recessions occur at different times. Changing economic conditions also affect various types of investment assets differently. By diversifying with a variety of assets, the value of your portfolio will not fluctuate as much during these changing periods.

Be a lender, not a borrower

To begin with modest assets and build a fortune obviously requires you to be a saver. Anyone seeking to become wealthy should put away 10 percent of earnings as a monthly savings. Those who save and are thrifty will grow wealthy; spendthrifts will become poor.

A magic formula exists called dollar cost averaging, in which you invest the same amount of money at regular intervals (monthly is best) in an investment where the price fluctuates. At the end of the investment period, your average cost will be below the average paid for the investment. In other words, your dollars will buy more shares when prices are low and fewer shares when prices are high, so that your average cost is low compared with the average for the market.

To grow wealthy, you must make your money work for you. In other words, be a lender, not a borrower. If you have a big mortgage on your home, the interest paid will more than double the cost of the home. On the other hand, if you own a mortgage on a house or income-producing real estate, the annual interest on that mortgage will compound and make a fortune for you. If you never borrow money, interest will always work for you and not against you. Those who understand interest get it ... those who don't pay it.

Thrift, common sense, and wise asset allocation can produce excellent results in the long run. For example, if you begin at age 35 to invest $17,000 annually in your IRA or retirement plan — where it can compound free of tax — and if you average a total annual return of 10 percent, you will accumulate nearly a million dollars by age 55.

Misconceptions abound

When it comes to investments, everyone has an opinion and misconceptions run rampant. These misconceptions are most prevalent and dangerous when it happens in the area of asset allocation. My consultations with doctors often manifest themselves as those who make an inappropriate rejection of a major investment asset category, which in the long run will be to the detriment of their portfolio. I know only too well that doctors sometimes refuse to invest in common stocks, even though this asset category may play an important part in developing the best investment strategy for them. Many of them have portfolios (80 percent in bonds) that reflect their comfort levels because of poor investment advice — i.e., "Invest in bonds only." This type of allocation is completely inappropriate; bonds will never give you the growth you need to accumulate wealth.

The strategy

Before you can decide on specific investments, you need a master plan for diversifying your dollars among the three classes of investments: stocks, bonds, and cash equivalents. That strategy is called asset allocation.

Asset allocation has as its foundation the idea that the capital markets are efficient. This process developed when the focus shifted from individual securities to the portfolio as a whole. There also was a shift of attention away from return enhancements in favor of risk reduction, which is achieved through the broad diversification of a portfolio. The important factors — investment objectives and goals, relevant time horizon, and risk tolerance — combine to determine whether your portfolio should be structured for greater principal stability with corresponding lower returns, or alternatively for larger growth at the risk of more volatility.

In either case, the goal is to use the best allocation across the various asset categories to achieve the highest expected return relative to the risk assumed.

The Brinson Study

A study of 91 pension plans provided dramatic support for the importance of asset allocation. The Brinson Study sought to attribute the variation of total returns among the plans due to three factors: asset allocation, market timing, and security selection. The study showed that, on average, a startling 93.5 percent of the variation could be explained by the asset allocation. Market timing accounted for 1.7 percent of the variation in the total returns among the plans, while security selection accounted for 4.8 percent of the variation in total returns among the plans. This study supports the notion that an asset-allocation policy is the primary determinant of investment performance, with market timing and security selection both playing very minor roles.

A review of history

Doctors are often unaware of the risks they face in investing. If these misconceptions go uncorrected, it is very likely that they will make portfolio decisions that are not in their best interests. One who fully understands inflation, interest rate risk, credit risk, and equity risk is in a much better position to make intelligent investment decisions appropriate for long-term objectives. This highlights the value of providing a detailed historical review of the capital markets.

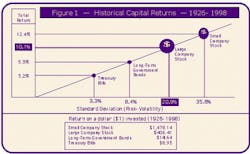

Figure 1 provides an excellent summary of the comparative performance of the major investment alternatives. The column labeled "Total Return" compares the historical compound annual returns for the various investment alternatives. Clearly, equity investments such as common stocks have had better returns than bonds over the long term, which, in turn, have outperformed Treasury bills. Correspondingly, by comparing their respective standard deviations (a measure of risk), we can see that the higher returns have been obtained at the risk of more volatility.

In comparing the returns of these investment alternatives, the impact that small incremental returns have had on wealth accumulation is surprising. For example, Treasury bills, with a compound annual return of 3.2 percent, resulted in the growth of a $1 investment to $8.93. By contrast, common stocks had a compound annual return of only 6.5 percent more, yet the initial $1 investment grew to $406.41 over the same time period. Similarly, small-company stocks had an incremental compound annual return of only 2.3 percent in excess of common stocks, yet this small additional return produced an astounding value of $1,478.14. These are clear illustrations of the miracle of compound interest.

The impact of standard deviation

Contrasted with these relatively modest incremental differences in compound annual returns, there are wide differences in the standard deviations of returns among various investment alternatives. Figure 1 shows that Treasury bills not only had the lowest historical compound return; they also had the lowest standard deviation.

Common-stock returns are higher than the total return of the best-performing, interest-generating alternative (corporate bonds). In essence, common-stock investors historically have had long-term capital appreciation sufficient not only to maintain but to enhance their purchasing power. This leaves the dividend income stream available for reinvesting, for income, or for spending. Because a common-stock portfolio can keep up with inflation on average over time, so will its dividend stream. Emphasis is on the phrase on average over time, because in the short-run, the much higher volatility of common stocks produces great uncertainty in returns.

Managing your money

Money management is simple, but not easy. It is simple, because the principles of successful investing are relatively few in number and are easy to understand. Although there are a variety of risks that everyone faces in money management, the two most important are inflation and volatility of returns. To the extent to which a portfolio is structured to avoid one of these risks, it unfortunately becomes exposed to the other. For this reason, you must determine which risk is more dangerous.

Time horizon, mainly, is the most important factor that will bring about the best result. For a short time horizon, volatility is a bigger risk than inflation. Such portfolios should, accordingly, follow an asset-allocation strategy that gives greater weight to stable principal-value, interest-generating investments (i.e., bonds). For long time horizons, inflation is the more significant danger, and these portfolios should, therefore, have larger allocations to equity investments.

But regardless of the time horizon, the risk-mitigating benefits of broad diversification emphasize the use of multiple asset classes for both conservative and aggressive investors alike.

Making the most of your money

Because money management is simple, it is within the capacity of all of us to be meaningfully involved in the investment decision-making process. It is neither necessary nor advisable for you to leave the major investment policy decisions to the sole discretion of a stockbroker. It is your money, and you are the one who will have to live with the results. You must become financially literate!

As you become better educated about the money-management process, your risk tolerance will change toward the strategy that is most appropriate, given the facts of your situation. The more you understand, the better your decisions will be. You can't help but benefit by having a realistic frame of reference for evaluating the end result. This will lead to greater staying power in the market, which is extremely important for the realization of your investment objectives. To be successful, you must be in it for the long-term.

Living with the uncertainties

We often mistakenly believe that stockbrokers should have a method to eliminate the uncertainties that go along with investing. But as we focus on the uncertainties inherent in money management, all we can hope to accomplish is to get a better picture of the uncertainties; we cannot eliminate them. In the wise words of an economist friend of mine: "The window to the financial future is opaque."

As difficult as it is to live with, uncertainty is not necessarily bad. For those of you with a long time horizon, short-run uncertainty is the engine that drives the higher returns of equity investing. If you understand this, you can use it to your advantage. There is a difference, though, between intellectually understanding something and living with the results on a day-to-day basis. Successful investing will always be as much of a psychological process as it is a money-management endeavor.

Money management is not easy. Without a very firm commitment to long-term investment policies within an asset-allocation framework, it is easy to become distracted by investment schemes that promise high returns with little or no risk. Those who depart from a long-term strategy to pursue those risky types of investments will, in the end, build portfolios in the same way they collect shells at the beach — by picking up whatever catches their eye at the moment.

The bottom line: There is no safe, quick, and easy way to build wealth. To this end, an old saying helps remind us: "If wishes were horses, beggars would ride." Always remember: Planning makes the difference. Until next month ...

The material for this article is an excerpt from Dr. Hugh F. Doherty's forthcoming book, Making the Most of Your Money, and is printed with Dr. Doherty's permission. For more information on this article, he can be reached at [email protected]

Words to the Wise on Investing

- Before you can decide on specific investments, you need a master plan — a strategy for how to divide your investing dollars among the three classes of investments: stocks, bonds, and cash equivalents. That strategy is called asset allocation.

- Asset allocation is dynamic. It is a strategy based on diversification; i.e., allocating your investing dollars among different types of investments.

- Portfolios range from the most aggressive (the most heavily invested in stocks) to the most conservative (the least invested in stocks). These approaches all have one thing in common: They all include stocks. The reason is that in order for your money to outlive you, you need to invest for growth the rest of your life.

- As you develop your asset-allocation plan, remember to consider all of your investing dollars — that is, investments in your retirement account and investments in your brokerage account.

- Research shows that adding some fixed-income investments (bonds, etc.) to your portfolio gives it more stability.

- Stock mutual funds are good both for building your retirement nest egg and for generating income through dividends and capital gains.

- Choosing individual stocks can be tough, so I suggest you allocate no more than 10 percent of your investing dollars to individual stocks.

- Consider only no-load mutual funds.

- Use index funds because of their simplicity and lower fees.

- Choose funds with a solid track record, not only for this year but for the life of the fund.

- If you choose individual stocks, look for quality by tracking a company's earnings trend. The more helpful number is earnings per share (EPS).

- Always look at the company's price/earnings ratio (P/E).

- The main reason you choose cash-equivalent investments in your portfolio is for liquidity.

- When you invest in bonds, you are generally better off doing so in your regular account, which is currently taxable.

- Stocks and stock mutual funds are usually the better choice for retirement accounts where taxes are deferred.

- Become financially literate. Must reading: "Asset Allocation" by Roger Gibson