You Can't Use What You Can't Reach

by David J. Ahearn, DDS

For more on this topic, go to www.dentaleconomics.com and search using the following key words: dental office chaos, Toyota Production System, Zero Changeover, Dr. David J. Ahearn, ergonomics, four–handed dentistry, Design/Ergonomics.

A problem has emerged in our profession over the past two decades. Increasing complexity has resulted in the breakdown of the dental treatment environment. Advances in technology, and with it the range of products needed to provide services, have led to sprawl in operatory setups and equipment deployment (see Fig. 1). Increasing procedural complexity has slowed treatment while widening the range of motion. These changes have simultaneously decreased per hour productivity when adjusted for inflation, without improving overall ergonomics. Only the increases due to advanced (in other words, more costly) procedures have helped dental incomes grow. The problem is simply that you cannot use that which you cannot reach.

Accommodations created by doctors in an effort to compensate for the increase in technology have been insufficient to offset the decrease in performance. Four–handed dentistry — a great innovation — was created primarily for the purpose of expanding the range of motion for the operator, rather than to actually have four hands providing treatment. Higher–performing products such as electric handpieces have increased cutting efficiency while increasing wrist stress. Even loupes have traded improved visual acuity for fixed static posture.

Unfortunately, dentists have had little instruction on how to translate this increased complexity to a more productive and healthier environment. An example of the disconnect between what we do and how it is actually accomplished is the operator's stool. It is our most basic tool, yet it has not been significantly improved in most practices. During the 50–plus years of sit–down dentistry, there has been little research on the ergonomics of operator's stools, and little education of the user regarding the objectives for this tool.

A fundamental activity early in basic military training is the use of the personal weapon. Trainees spend countless hours learning every aspect of what is termed their weapon. By contrast, in dentistry significant effort is placed on the result of dental treatment (what occurs at the end of a handpiece), while little effort is made to increase the operator's understanding of how those results are obtained physically (see Fig. 2). The outcome is that technological improvements have resulted in little reduction to the incidents of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in dentistry over the past decades.

Patient chairs, an ideal opportunity for improved ergonomic function for the operator, became wider and more plush over the decades, decreasing operator access for the benefit of comfort for the visitor (most of whom are only in the office for a couple of hour–long visits a year).

So, the question is — how do we reset our sights on a simpler, more productive, and healthier treatment environment? (See Fig. 3 of a poor environment.)

It is my observation that the Toyota Production System principles of Just in Time and Zero Changeover can be applied as solutions to these problems. Just in Time principles will remove bulk inventory from the treatment environment while creating a physiologic range of motion for those products needed rapidly to perform core tasks.

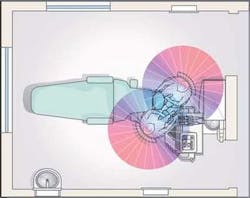

Further, the principles of Zero Changeover can then be applied so that operatories can be reconfigured in seconds for additional or different procedures as needed. This fundamental change in deployment has both ergonomic and productivity ramifications. With a significant decrease in operator range of motion, doctors and staff are able to function at a much more productive level (see Fig. 4). Inventory volumes plummet while productivity increases.

Concomitantly, room sizes can decrease while the availability of products and technology increases. New technology can be introduced into the work environment much more rapidly as setup and restocking times approach zero. This is because any product can now be introduced into any treatment room, at any time, and in any location that is within the primary (direct reach) ergonomic zone.

Given the compelling reasons for pursuing these benefits, the question becomes: What are the obstacles to adopting Lean principles in the dental treatment environment? The primary obstacle to this rethinking of the operatory is that it is counterintuitive.

Instinctively, the response to running out of supplies during a procedure is to stock more of that item rather than stocking less with a much better flow. Here is an outline for improving practice health and production using the Lean principles of Just in Time and Zero Changeover.

1 List all the products needed for standard practice procedures and estimate a volume needed for 10 days of practice.

2 Throw out all of the irrelevant product packaging included with the products in Step 1.

3 Segregate your disposable product requirements and stock these in an easily accessible storage container.

4 Consolidate core, preferred, daily products into a single Zirc, Clive Craig, or Midmark container. Most practices are easily able to fit their typical materials for core procedures into a single Zirc tub.

5 Post a picture of the filled containers in the resupply area so that anyone can easily restock.

6 Keep items that are rarely used or used on a limited basis in their original packaging with their instructions in a central resupply area, categorized by use (e.g., endodontics, oral surgery, or other). Should a new product make its way into daily use, it is then reassigned in one of the locations for the more frequently used products as stated in steps 2 and 3.

7 In order to mobilize the less frequently used but vital technologies and products, segregate them into groups suitable for rapid deployment. The use of rapidly movable storage and delivery systems designed for use on the doctor side of the treatment delivery process permits specialty procedure access directly to the dentist, who in most instances is best able to manage lesser–used technology.

Mobile deployment markedly reduces specialty supply volume, minimizes staff confusion, and most importantly permits setup for specialty procedures in any room in less than 45 seconds (see Fig. 5). Once inventory becomes balanced within the usable range of motion, it is possible to focus on actual physical deployment — the first aspect of which is visibility. There is some controversy regarding the ideal focal length from which to perform dental care. It is my observation that the majority of magnification users believe that it's necessary to pursue the longest possible focal length that will result in a very upright (and presumably more healthy) posture.

Others, such as those who adhere to the Performance Logic School, believe a much shorter focal length is healthier. Regardless of the focal length, what is clear is that the operator and assistant must be able to function at close proximity to the treatment zone (see Fig. 6).

With all of the pressure on practitioners to learn to work with more complex systems and techniques, it is all too easy to lose sight of basic ergonomic principles. A reengineering process that streamlines core function and the time to complete tasks is often the simplest and most productive solution to improving or eliminating practitioner MSDs (see Fig. 7), reduce stress, and greatly improve productivity.

David J. Ahearn, DDS, is a full–time practicing general dentist. His office consistently ranks in the top 1% of practices nationwide. He is the president of Design/Ergonomics. Reach him at (800) 275–2547 or by e–mail at [email protected].