by Bradley Dykstra, DDS

Can you save your way to prosperity by cutting overhead?

How profitable is your practice? What is the best way to increase or maximize it? Should you raise fees, or is it more profitable to lower them? Should you eliminate reduced fee programs or embrace more of them? Are you sure the practice is really profitable, or are you working for less than an associate would make?

These are questions that practitioners should ask themselves both in good times and in financially challenging times such as now, even if the truth is painful. In addition, much of the advice we read in our journals is incomplete, confusing, or even misleading.

Should you lower your fees in these times of economic uncertainty, leave them untouched, or raise them? Should you increase your marketing budget, minimize it, or eliminate it completely? Should you increase the investment in new technology, or stay with what you have? The following answers derived from sound business principles may surprise you.

To understand the financial dynamics and drivers of profitability, we will examine the most basic business principles that apply to any business, including dentistry. In the most basic form, the formula for determining practice profitability is total income (revenue) minus total expenses equals net practice profit. Often the problem is not being clear on what comprises these three numbers and the variables that affect them.

To better understand what is going on, each of these three variables -- total income, total expenses, and total profit -- will be expanded and explained. Once you grasp these concepts, the decision-making process becomes easier and the results more predictable. (In this discussion, only real money inflows and outflows from the practice are considered. This is in an attempt to clarify what affects the bottom line of the practice from a cash-in/cash-out standpoint, so depreciation will be ignored.)

Total income:

Total income equals total number of patients seen times income per patient (number of procedures per patient times fee per procedure)

Total income generated may appear to be the easiest concept, but arriving at the true number can be difficult. Total income is the sum total of all of the income that the practice collects minus any refunds or reimbursements. Many dentists erroneously assume that their monthly or yearly gross production numbers or total fees generated that show up on their PMS reports are their total income. Unless it is a cash practice with a 100% collection percentage, this is not the case. The adjusted collection number from the PMS reports will often get to this number. The number needed is the total amount of money collected, which means exactly that -- add up the total amount of cash, checks, and net credit card payments to get this number. Any money in accounts receivable is not income until it is collected. If a check bounces, it comes off the income until the amount is made good.

What are the variables that have an effect on the total amount of fees generated? The answer is, each of the three items that make up total income -- patients seen, procedures per patient, and fee per procedure. How does altering each of these affect the top line income?

The first and most important variable is the fee schedule: the higher the fees, the higher the income generation potential. A connected and obvious corollary is the effect that reduced fee programs such as HMOs, PPOs, or other reduced fee insurance programs will have on the bottom line. The more of these you participate in, the lower your net collection amount will be, and the higher the overhead percentage.

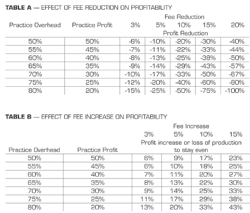

Before embracing any reduced fee program, take the time to calculate the effect on your bottom line (see chart A). Another temptation during times of economic uncertainty is to freeze the fee schedule. If you do this and your costs of providing services increase, even marginally, your net profitability will decrease. Remember the formula -- income minus expenses equals profit. There are no out-of-pocket costs associated with raising fees.

A greater temptation with even more severe financial implications is to reduce your fee schedule. If the practice overhead is 60% (an average practice today), reducing fees by 10% will reduce the net income by 25% (see chart A). Put another way, if you reduce your fees by 10%, you will have to produce 25% more procedures plus your variable costs (lab and supplies) to break even. If your overhead is 70%, the effect on the bottom line is even more dramatic -- you will have to increase your production by 33% to maintain the same net profit.

On the other side of the equation, if your overhead is 70% and you increase fees by 5%, your net income will increase by 14% (see chart B). Put another way, you can do 14% (plus variable costs) less production while maintaining the same level of net income. Do you really want to freeze your fees? Does the temptation to lower them or embrace more reduced fee programs make any sense at all?

What are some additional ways to increase the total amount of fees generated? The most obvious one is to see more patients, which will result in getting more patients through the door or working more efficiently. If the practice is unmanageable and disorganized, engage a good practice management consultant to help you institute systems to increase your capacity.

This also raises the marketing question. Do you want to decrease your marketing budget, freeze it, or increase it? Since the majority of your costs are fixed, at least in the short term, anything you can do to increase income will increase net profit. If you increase the marketing budget from 3% to 5% (assuming a $100,000 a month production, from $3,000 to $5,000), you will have to bring in only $2,000 (plus lab and supply costs) more in production to break even. Taking in one to two patients should help you easily do this in the short term. The long-term benefits of having more patients are even greater.

Fixed costs are costs that you cannot change quickly (less than six months) -- employee expenses (normally), facilities, and insurance.

Variable costs are costs that correlate with the amount of work done -- supplies, lab, and associate or contract labor compensation.

A final way to increase revenue is to increase the number of services you provide for your existing patients. Are you presenting all the treatment they really need, or are you holding back for fear of overwhelming them or assuming they cannot afford treatment? Do you diagnose and present treatment based on their insurance coverage or their true needs? Are you addressing their periodontal and occlusal issues, or are you letting them ride for a while?

Take a hard look at the practice patterns. Are there services you are now referring out that could be done in-house, such as endo, perio, extractions, or treating TMD and bruxism? If you have an increased amount of free time, consider learning a new procedure or treatment modality. Restoring and/or placing implants, Invisalign orthodontics, or laser dentistry are a few examples.

Is your treatment acceptance rate good, or could it use a little improvement? If you are not currently using digital intraoral and extraoral cameras in your diagnosis and treatment planning, this would be a great investment. When patients can see what you see, they truly start to understand their problems, and most patients will ask for the needed treatment. If your case acceptance goes up by 10% and your overhead is at 70%, your net income will go up by over 25% minus variable costs.

Total expenses

Determining the total expenses is very straightforward. Look at the check register or QuickBooks Profit and Loss Report each month and at the end of the year, and then determine the total outflow of cash via checks or credit card payments. What are the variables that affect expenses? The easiest way is to think of them in two basic categories -- fixed expenses and variable expenses. In the short term (under one year), the variable expenses are ones that go up and down each month and are correlated with your production numbers. In most cases there are only two -- the lab bill and supply bill. Others might possibly be the marketing budget and contract labor. Fixed expenses include all of the rest -- labor, facilities, insurance, etc. They stay the same no matter what the production and collection numbers are each month. Some may consider labor a variable cost, but in the short term it is a fixed cost. In the long term, which is anything over one year, many expenses can be considered variable.

Dentists are often tempted to find ways to cut expenses, reduce employees, or use cheaper supplies. Although it is always important to run a lean practice, cutting expenses is not generally the way to increase practice net income over time. Take supplies, for example. If the normal supply bill is 5% of production and you find a way to save 10% on the supply bill (almost impossible), this translates into only a half of 1% (5%-.5%=4.5%) increase in practice net income. It would only take .02% increase in production or fee increase to accomplish the same result. Long term, you cannot save your way to prosperity by simply cutting expenses.

This temptation to cut costs also segues directly into the marketing budget. If the marketing budget is 4% of practice income (high for most practices) and it is reduced to 2%, it will result in an immediate 2% increase in practice net income. The bigger question is what will the effects be over the next six to 12 months? If the marketing program is effective, it will generate more income than it costs. Assume that cutting the marketing budget by 50% (4% to 2%) reduces new patient flow by 30% and production by 10%; therefore the result is very detrimental to the bottom line of the practice. If you are not tracking the results of the marketing efforts, it is time to do so. Eliminate what does not work and increase what does work.

A similar temptation may be to reduce the number of hygiene days in the practice. Again, remember that about 60% of the doctor production comes from the hygiene area. Do everything you can to keep the hygiene department strong and productive. Take the extra time to build and reinforce the value of the preventive care appointments for your patients.

The best way to control overhead percentages is to increase production

Net practice income is what is left after subtracting all of the expenses from the total income. What should your net practice income (before personal taxes) be? A benchmark to aim for is a combination of two numbers. The first is being paid for the work you as the dentist produce. If the going rate for compensating an associate is 33%, the owner dentist should be compensated at least at this level. The second number is being paid a return on the investment of the practice. A good rule of thumb is to expect a 10% return of the investment in the practice. If you have invested $1 million in the practice, the return should be 10% or $100,000 plus 33% of the practice income generated. If the practice income is $1 million, this means a total practice income of $430,000 or 43% (33% earned from production and 10% from return on investment in the practice). This translates into a 57% overhead, which is not easy to achieve, but with good systems in place, is possible.

In determining the net income, it is also important to take into account a few add-backs or additions taken from the total expense department. These may include pension plan contributions for the owner/doctor, car allowances, health insurance, and continuing education expenses. If the net practice income of a million dollar practice is only 35%, but $100,000 was placed into a retirement plan for the doctor, the real income is 45%. Once you understand the numbers of the practice, the decision-making process becomes much easier and effective.

In summary, if the goal is to maximize practice profitability, remember the formula -- Total practice income (total number of patients seen times income per patient [procedures per patient times fee per procedure]) minus total expenses (variable expenses plus fixed expenses) equals net practice profit. Focus on the real drivers of income growth -- increasing the number of patients, procedures per patient, and fee for procedure. Reduce overhead to a healthy level, but keeping the focus here will not bring long-term growth or prosperity.

Bradley Dykstra, DDS, is a general dentist in private practice in Hudsonville, Michigan. He is a graduate of the University of Michigan's dental school and received his MBA from Grand Valley State University. Dr. Dykstra speaks on integrating technology into the dental office and consults through his company, Anchor Dental Consulting. You can reach him at (616) 669-6600, or send an email to [email protected].

Past DE Issues